Yr Hen Iaith part twenty nine: Guto’r Glyn (c.1410 – c.1493)

Continuing our series of articles to accompany the podcast series Yr Hen Iaith. This is episode twenty nine.

Jerry Hunter

In our last instalment we concentrated on the ymrysonau, debates conducted using the strict-metre cywydd form, an interesting aspect of Welsh bardic culture and practice. In this episode we focus on Guto’r Glyn, a prolific poet from the fifteenth-century.

Unlike many of the other cywyddwyr, he did not compose poetry about love and nature. (It is of course possible that he did, but that those poems have not survived; however, given the fact that more than 100 of his compositions have survived in manuscript copies, it is a pretty safe assumption that he did not).

He used the cywydd form almost exclusively for singing mawl, praise. It is thus not surprising that we find him entering into an ymryson debating the role of the bard in the context of patronage.

Another bard, Hywel Dafi, seems to have remained in Raglan, the court of a choice patron, Sir William Herbert. Guto, on the other hand, believed that a bard should engage in clera, which meant travelling around Wales and singing praise to a variety of different patrons:

Ni fawl Hywel ryfelwr

Na dyn gwych, onid un gŵr;

Ni chyrch i Wynedd, ni chân,

Ni threigl unwaith o Raglan.

Nid saethydd beunydd bennod

Y dyn ni wŷl ond un nod[.]

‘Hywel does not praise a warrior

Or a brilliant person, except for one man;

He doesn’t travel to Gwynedd, he doesn’t sing [there],

He doesn’t once leave Rhaglan.

An archer [who is at it shooting] daily is not

The man who only sees one target.’

The metaphor which Guto used to rebuke his contemporary resonates pointedly –pun intended! – with an important aspect of his own life: he served as an archer in the English army during in France during some of the campaigns of the ‘Hundred Years War’.

It’s worth including a bit of scholarly history here. We wouldn’t be able to discuss medieval Welsh literary in any depth without the awe-inspiring work done by previous generations of scholars. While a great many highly-skilled editors have contributed invaluably over the years, the stand-out figure from the first half of the twentieth century is Ifor Williams of (what is now) Bangor University.

However, past glories aside, the last thirty yeas is really the golden age in this context, thanks to several large and long-running projects run by University of Wales’ Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies and the many scholars who have worked there since the early 1990s.

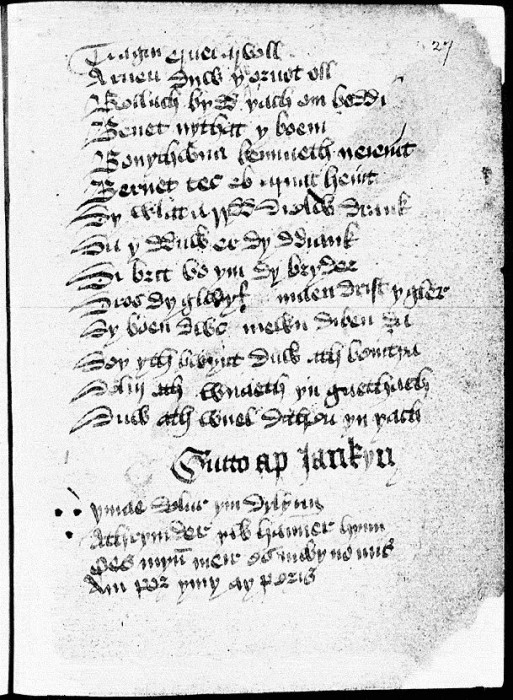

One of these projects involved the editing of all of Guto’r Glyn’s work and examining what we know about his life in detail.

Copyright: Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru / National Library of Wales

A critic and analytical thinker more than an editor, Saunders Lewis contributed a great deal to our understanding of many aspects of Welsh literature and its history.

A piece he published late in life discusses ‘The Military Career of Guto’r Glyn’ (‘Gyrfa Filwrol Guto’r Glyn’). He suggested that Guto was one of the longbowmen serving in France, a theory proven to be true by hard evidence uncovered during the course Centre’s research project.

It’s worth noting that this scholarly history has implications for fields beyond the study of literature, strictly speaking. My co-presenter, Richard Wyn Jones, is a political science best known in Wales as an expert on Welsh politics.

He has written about this piece of scholarship by Saunders Lewis and, as he notes in this episode of Yr Hen Iaith, it is significant because it says a lot about Saunders Lewis as well as Guto’r Glyn, demonstrating that, unlike so many other Plaid Cymru members who were/are pacificists, Saunders believed that a military career could be an honourable vocation.

As already suggested, that military career can be seen to inflect aspects of Guto’s poetry. In a cywydd addressed to Sir Rhisiart Gethin, Guto complains that the patron has not yet returned from France after campaigning there with the army.

The Welsh warrior was a ‘captain’ in the English army, and, while ‘every (other) English captain’ (pob capten o sifften Sais) has returned, Rhisiart has not. Interestingly Rhisiart’s father was Rhys Gethin, who fought with Owain Glyndŵr against the English army.

While working within the often strict confines of tradition, Guto’r Glyn often sang praise in wonderfully original ways. In praising the generosity of Tomas ap Watgyn of Llanddewi Rhydderch, Guto provides a humorously absurd reworking of military experience, claiming that poets must fight to finish the vast quantities of wine served in the patron’s house.

Cynhaliwn drin â gwin Gwent, he exclaims – ‘we will wage war against the wine of Gwent’ – describing the ‘praise’ ([c]lod) which they sing to Tomas as the ‘banner’ ([b]aner) in this particular war, with the gwin gwyn, ‘white wine’ being the Dolffin, the ‘Dauphin’, the French prince leading the opposing army.

Having lived a long and – by all accounts – very active life, Guto retired in old age to the abbey of Glyn-y-Groes (or Valle Crucis), near Llangollen. Guto praised the abbot, Dafydd ab Ieuan, thanking him for the care provided by means of a self-satirizing partial apology. He describes himself as a blind, needy old man, talking endlessly about the old days and calling out from his bed for help, troubling the monks who tend him:

Siaradus o ŵr ydwyf,

Sôn am hen ddynion ydd wyf,

‘I am a talkative man,

I go on about old men.’

And:

Tyngu a wna teulu’r tŷ

Mae galw a wnaf o’m gwely.

‘The host of the house swears

That I call out from my bed.’

This self-satire rings true. If partly humorous, it is also a sad and sobering picture of an infirm old man, bereft of the strength he used to enjoy and forced to depend on others for the most basic of care. It is also a powerfully original and personal inflection of the age-old ubi sunt? theme, a way of expressing sadness for things and people lost as time goes by. This is crystalized memorably in the cywydd’s opening couplet:

Mae’r henwyr? Ai meirw’r rheini?

Hynaf oll heno wyf i.

‘Where are the old men? Are they dead?

Tonight I am the oldest one of all.’

Earlier in life, Guto provided a different mediation on the fragility of life in a poem mourning the death of Llywelyn ab y Moel, and older poet (thought to have served in the forces of Owain Glyndŵr during his Rebellion). As Llywelyn was laid to rest in the monastery of Ystrad Marchell (or Strata Marecella), it beings with a powerful line, the cynghanedd’s internal rhyme linking the poet’s coffin (arch) to the place where it was buried: Mae arch yn Ystrad Marchell (‘There is a coffin in Ystrad Marchell). In listing the virtues buried with the dead poet, he refers to his artistry as well as his prowess in war:

A chledd, dewredd dihareb,

A cherdd – yn iach ni chwardd neb[.’

‘And a sword, proverbial bravery,

And song/poetry – farewell; no one laughs [now].’

One wonders if Guto, when an old man in bed in that other monastery, did not recall these words when contemplating his own imminent death.

Further reading:

Guto’r Glyn.net: http://www.gutorglyn.net/gutorglyn/index/

Saunders Lewis, ‘Gyrfa Filwrol Guto’r Glyn’, yn Ysgrifau Beirniadol IX (1976).

Richard Wyn Jones, Rhoi Cymru’n Gyntaf: Syniadaeth Wleidyddol Plaid Cymru, cyfrol 1 (2007), pp. 55-107.

Catch up with all the previous episodes in this series here

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.