Yr Hen Iaith part twenty: Poetry, Princes and Power

Continuing our series of articles to accompany the podcast series Yr Hen Iaith. This is episode twenty.

Jerry Hunter

Discussing literary texts in relation to specific historical contexts can be difficult, especially when dealing with literature composed many centuries ago. That is one of the many reasons which makes studying ‘the Poets of the Princes’ such an exciting thing.

This large body of poetry – attributed to more than thirty poets whose names are known to us, and totalling more than 12,000 lines of verse – was produced during a distinct period in Welsh history.

This is the ‘Age of the Princes’ beginning with Gruffudd ap Cynan, king of Gwynedd, who died in 1137, and ending with the death of his descendant, Llewelyn ap Gruffydd, in 1282.

In addition to defining ‘The Age of the Princes’ by referring to this royal lineage, it should also be defined by the challenges and threats posed to these Welsh rulers by the arrival of the Normans.

In the work of the Poets of the Princes we have a large collection of literature fashioned by highly trained professional poets and this body of written art is tied intimately to the socio-economic and political reality of the period.

The power of words

These medieval Welsh poets composed – or ‘sang’ – praise to Welsh kings or princes. This praise helped maintain the good name of those leaders and thus helped maintain the political structure.

Modern students sometimes look at this literature as political propaganda created by salaried ‘spin doctors’, for we know that poets were rewarded for canu mawl (‘composing’ or ‘singing praise’).

However, that is an anachronistic view which obscures the deep relationship between political power, the nature of art and the essence of medieval Welsh society. Words had power, and words which are created skilfully to be both beautiful and memorable have the power to create.

Of course, this is by no means a uniquely Welsh concept; for example, think of the way in which God is said to create by means of speaking at the start of the Hebrew Torah and the Christian Old Testament.

Even in the 21st century, words spoken in certain circumstances have lasting and serious consequences (for example, swearing an oath in a court of law or pronouncing vows in marriage service).

Words create things, and the highly-crafted words of the Poets of the Princes created and re-created lasting praise essential to the reputation of those rulers.

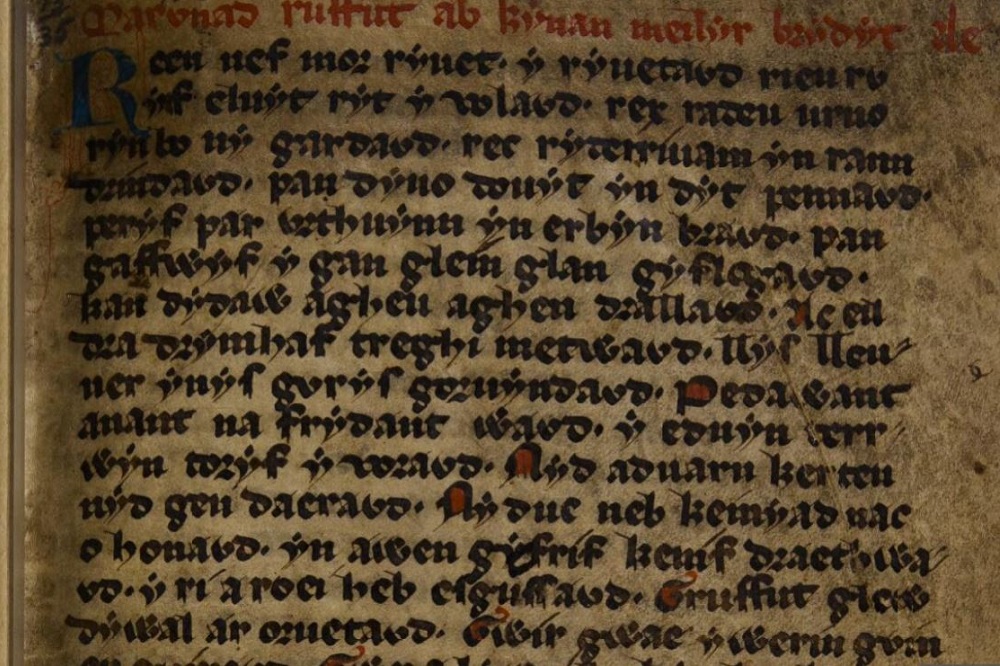

While compositions by some of these poets are found in various manuscripts, there is one which is of supreme importance here – the Hendregadredd Manuscript.

Named for the plasty near Cricieth where it was rediscovered – apparently hidden away in a wardrobe – in 1910, it is kept in the National Library of Wales. This manuscript was surely produced at the Cistercian abbey of Strata Florida.

Lasting monument

According to our foremost expert on medieval Welsh manuscripts, Daniel Huws, it is ‘a striking example of a collaborative work… during the first quarter of the fourteenth century, nineteen good scribes, near-contemporaries, made systematic additions to this carefully planned anthology of court poetry.’[1]

The Hendregadredd Manuscript is the result of a coherent project which was executed with enthusiasm.

As Daniel Huws says, it is ‘a collection, and an orderly one, of the work of the Poets of the Princes, beginning chronologically, with Meilyr and closing with the fall of Llywelyn. [The architect of this project] had already within a generation of 1282 created our literary abstraction “The Poets of the Princes.”’[2]

This is profoundly important; shortly after Edward I’s conquest of Wales in 1282, an ambitious project was set in motion in order to bring together and preserve the poetry of the period which ended with that conquest.

The Hendregadredd Manuscript contains a literary canon which defines a period in history and serves as a lasting monument to the Welsh social and political reality which had just been shattered.

Elegy

As has been noted already, the work of Meilyr Brydydd (or ‘Meilyr the Poet’) begins this literary canon. His marwnad or elegy for Gruffudd ap Cynan is an excellent example of its kind.

If poets praised patrons in life, creating a bardic monument to them served them in death – by reinforcing dynastic foundations for the deceased ruler’s son and by entreating heaven on behalf of the deceased ruler’s soul.

We might imagine that this elegy was performed during the funeral service or perhaps at another religious ceremony following the king’s death. It would certainly resonate with prayers being sung or recited for the king’s soul. It begins by praising God:

Rhên nef, mor rhyfedd Ei ryfeddawd,

Rhiau, Rhwyf elfydd, rhydd Ei folawd.

‘Heaven’s lord, so wondrous is His wonder,

Lord, Ruler of the world, His praise is expansive.’

Song of praise

When Meilyr moves from praising God to praising Gruffudd ap Cynan, he also affirms the power and importance of his own bardic enterprise.

For example, he exclaims that ‘An earnest song of praise is not false’(nid gau daerwawd ) and he states that awen – bardic inspiration – is behind his composition.

As is typical with this kind of poetry, Meilyr praises Gruffudd’s generosity extensively; if this is thanks for the patronage which the poet received from the king, it also draws attention to the fact that a good ruler enriches others around him (we are centuries away from democracy, and this might be seen as a medieval Welsh form of ‘trickle-down economics’).

Central are a number of lines which describe the king’s ferocity in battle, contrasting his energetic defeat of wordly enemies with the fact that his body is now still in its grave, his soul awaiting final judgement.

Gŵr a lywai lu cyn bu breuawd,

Blaidd byddin orthew yn nerr blyngawd!

Er perygl preiddwyr peri ffosawd,

Pasgadur cynrain, Prydain briawd

‘A man who led a host before he was broken [dead],

A great army’s wolf in a sad oaken coffin,

He caused combat to the terror of those who would despoil

One who supported princes, Britain’s true master.’

One section of the elegy seems to describe a specific battle in which Gruffudd defeated the Anglo-Norman king, Henry I:

Dybu brenin Lloegr yn lluyddawg,

Cyd doeth ef nid aeth yn warthegawg

‘The king of England came with a host,

But although he came he did not leave with stolen cattle.’

And in the final line, Meilyr Brydydd describes Gruffudd ap Cynan as Modrydaf Cymry, ‘Leader of the Welsh’.

This poem is pervaded by a celebration of political authority, including an emphasis on the fact that the dead ruler was a Welsh king who opposed foreign invaders.

In addition to referring to Meilyr Brydydd as the first of the Poets of the Prince, we should also describe him as a King’s Poet.

Further Reading:

Daniel Huws, Medieval Welsh Manuscripts (Cardiff & Aberystwyth, 2000).

J.E. Caerwyn Williams a Peredur I. Lynch (eds.), Gwaith Meilyr Brydydd a’i Ddisgynyddion (Caerdydd, 1994).

Notes

[1] Daniel Huws, ‘The Medieval Manuscripts of Wales’, yn Medieval Welsh Manuscripts (Cardiff & Aberystwyth, 2000), p.14.

[2] Daniel Huws, ‘The Medieval Manuscripts of Wales’ and ‘The Hendregadredd Manuscript’, yn Medieval Welsh Manuscripts (Cardiff & Aberystwyth, 2000), pp. 14 and 213.

Catch up on the previous episodes here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.