Yr Hen Iaith part two: The Black Book of Carmarthen and The Book of Taliesin

Yr Hen Iaith: Episode 2

Continuing our series accompanying Yr Hen Iaith podcast we explore The Black Book of Carmarthen, the Book of Taliesin, early Welsh writing and the nature of manuscripts.

Jerry Hunter

Let’s begin with a simple fact: manuscripts are fragile things.

Insects eat them (think of a literal bookworm). Fire destroys them. Smoke damages them. The Welsh climate is a villain in this story as well; manuscripts mould and rot in damp conditions.

And when Protestantism was forced on Wales by Henry VIII in the 1530s, monasteries were dissolved – that is, destroyed – and monastic libraries were lost. How many medieval Welsh manuscripts and how many works of Welsh literature were lost because of these factors?

We have no way of knowing, but there is one sobering suggestion as to the scale of the loss: it is known that there were 242 manuscripts in the Welsh Cistercian abbey at Margam, and it seems that not one of these ‘books’ has survived.

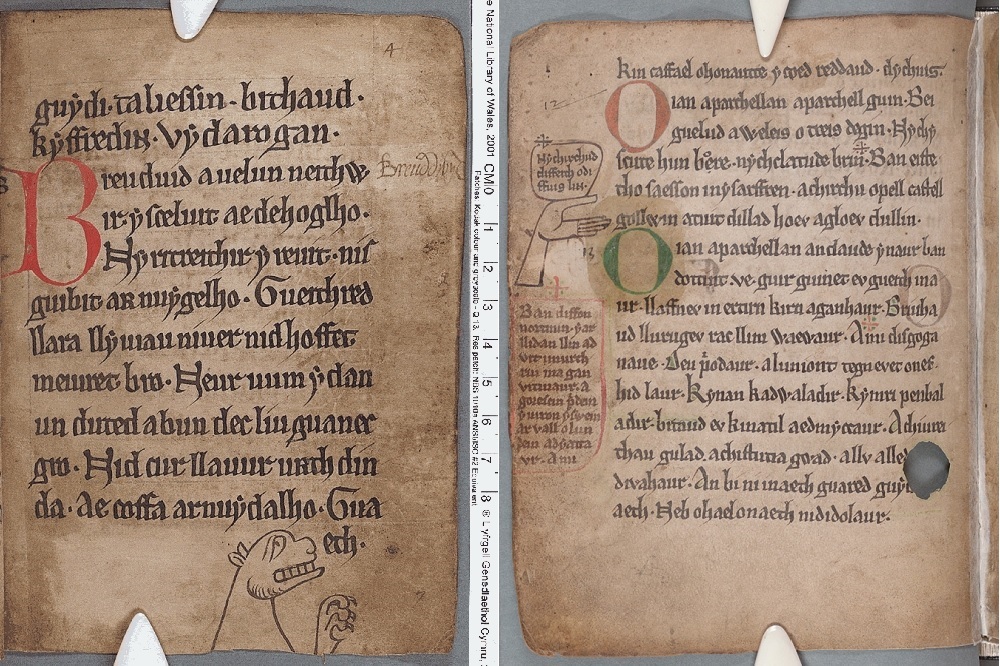

In this episode of Yr Hen Iaith (‘The Old Language’), we discuss the earliest surviving Welsh manuscript, Llyfr Du Caerfyrddin, The Black Book of Carmarthen, so named because of the colour of its binding.

It was created around the year 1250, most likely in the Augustinian priory of St. John and Teulyddog at Carmarthen, where it was found when that monastic house was dissolved by Henry VIII’s agents.

This manuscript is thus a hugely important literary artefact, being the first Welsh ‘book’ to beat all of the odds and survive.

Literary graffiti

While the Black Book of Carmarthen is the earliest manuscript written completely in Welsh, there are earlier examples of written Welsh – many of them from the Old Welsh period (c.750-c.1150).

Perhaps not surprisingly given the fragility of manuscripts, the earliest example of Welsh writing was entrusted to a much more durable medium, stone.

Carreg Cadfan, from Tywyn in southern Gwynedd, has Welsh words which were carved on it between c.750 and c.820, commemorating people buried at or near the place where it was erected.

There are some surviving Latin manuscripts which are earlier than the Black Book of Carmarthen, and some of these contains short texts in Old Welsh, added as notes or marginalia (one might think of them as literary graffiti).

These include the earliest surviving Welsh poetry written down, two series of englynion. It’s worth noting that versions of the englyn strict-metre form are still used widely by Welsh-language poets in the 21st century; this is an old and enduring literary tradition!

Written between c.850 and c.910, one is religious in nature and the other suggests a narrative context, describing in beautifully stark terms the circumstances of two warriors drinking in silence at night, apparently having lost the rest of their warband in battle.

It’s worth mentioning another of these Old Welsh texts, the so-called Computus fragment, written during the early 10th century. As Easter is celebrated on different calendar days, calculating the date of Easter is an extremely important matter for the Christian church.

This text explains how to use a diagram or chart to study the moon and stars and calculate the date of Easter.

Welsh has always been a language learning, and this text proves that the kinds of learning expressed and explored through the language have always included science – at least from the Old Welsh period.

All of these Old Welsh texts suggest that writing the language was already a well-developed skill. Scholars can tell by the way in which words are formed that these letters weren’t carved or written by people doing this for the first time.

There was an established tradition of writing in Welsh, even though most products of that early Welsh literacy have not survived.

Praise poetry

That context allows us to appreciate the seismic importance of the Black Book of Carmarthen – the first manuscript written entirely in Welsh which has survived. The history of writing aside, this manuscript is also an extremely important collection of literature.

Only poetry is contained in the Black Book, all written by a single person, surely a member of the Augustinian priory’s monastic community. In studying its contents, we can sense the honed interest and focussed purpose of the man who created this early anthology of Welsh verse.

There is religious poetry (not surprising, given the context in which it was written), praise poetry to Welsh princes (more on this in a later episode), and poetry associated with traditional narrative.

For example, Englynion y Beddau, ‘the Stanzas of the Graves’, lists places where legendary heroes are buried, famously refusing to name the location of the grave of that most important of figures, Arthur, stating instead that his grave is anoeth byd, ‘a wonder of the world’ or ‘a thing difficult to find in the world’.

Myrddin

Many of the Black Book’s poems are connected with the legendary poet Myrddin (whom we won’t call by the English name later attached to him by some writers, Merlin).

Remember that this manuscript was created in Carmarthen, Caerfyrddin in Welsh (caer, ‘fortress’ + Myrddin, or ‘Myrddin’s fortress’).

Often prophetic in nature, these dizzying compositions meld tantalizing glimpses of the poet’s current state – wandering in the wilderness, beset by grief and avoiding society – with his visions of the future.

The very first poem in the collection is the Ymddiddan or ‘Dialogue’ between Myrddin and another legendary poet, Taliesin.

Both of these figures are described in other texts as having supernatural powers, and in one sense they might be seen as competing for pre-eminence within the Welsh literary tradition.

Interestingly, and not surprisingly given the Caerfyrddin bias of the manuscript’s creator, this poem ends with Myrddin having the last word: Can ys mi myrtin guydi taliessin / Bithaud kyffredin vy darogan, ‘Since I, Myrddin, [come?] after Taliesin / my prophecy will be common’.

This can be taken as saying that Myrddin outlasts the other poet and that his darogan or prophecy will thus be known commonly throughout the land.

Prophet

If losing out to Myrddin in the Black Book, Taliesin gets his share of attention in Welsh manuscript culture.

The Book of Taliesin, written during the first half of the fourteenth century, is another collection poetry, with Taliesin himself as the organizing principle driving the work.

There is praise poetry from the ‘Old North’ attributed to the figure sometimes called ‘the historical Taliesin’ as well as a great deal of poetry associated with the poet’s legendary manifestation.

This is Taliesin the all-knowing prophet, capable of supernatural feats and described in later narratives as being born anew in each age. Taliesin became a personified suggestion that the power and spirit of Welsh poetry lives forever.

Like the Black Book of Carmarthen, the Book of Taliesin is now kept in the National Library of Wales, the safest of homes for medieval manuscripts which have survived all of the factors ranged against them during the first years of their existence.

Catch up on the first installment here

Both books are available online thanks to digitisation work carried out at Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru / The National Library of Wales : The Black Book of Carmarthen and The Book of Taliesin

Further Reading:

Ifor Williams, The Beginnings of Welsh Poetry (Cardiff: UWP, 1980)

Meirion Pennar, The Black Book of Carmarthen (Llanerch Press,1989)

Marged Haycock (ed. and trans.), Legendary Poems from the Book of Taliesin

(Aberystwyth: CMCS Publications, 2007)

Gwyneth Lewis and Rowan Williams, The Book of Taliesin: Poems of Warfare and Praise in an Enchanted Britain (Penguin, 2019)

Patrick Sims-Williams, The uses of writing in early medieval Wales, in Huw Pryce

(ed.), Literacy in Medieval Celtic Societies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998)

Daniel Huws, Medieval Welsh Manuscripts (Cardiff: UWP, 2002)

Aled Llion Jones, Darogan: Prophecy, Lament and Absent Heroes in Medieval Welsh Literature (Cardiff: UWP, 2013)

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Can I point out that Caerfyrddin is not named after a person,the name means caer a fortress ,myr (mor) the sea and din another word for fortress,as in Caeredin (Edinburgh},another tautologous name,and also in Dinbych.