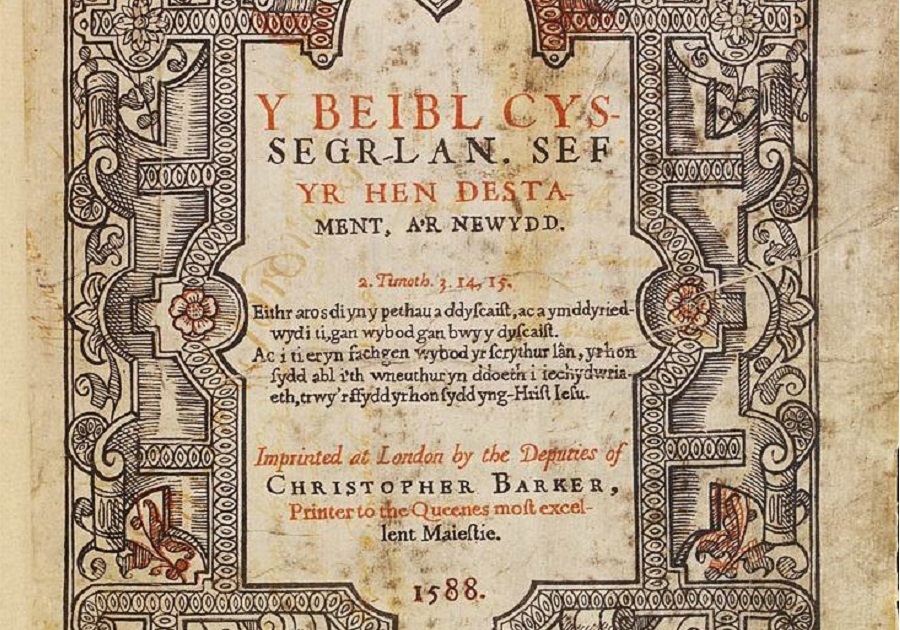

Yr Hen Iaith party forty five: The 1588 Bible and the literary language

Jerry Hunter

We continue the history of Welsh literature to accompany the second series of podcasts in which Jerry Hunter guides fellow academic Richard Wyn Jones through the centuries.This is episode 45.

Welsh is a literary language like no other. This is a simple but profound fact which readers of Welsh-language literature often take for granted.

It’s also something which needs to be explained in depth to people not familiar with Welsh. Let’s assume that you speak English as a first language and sometimes have to write in a formal context (doing administrative work as part of your job or perhaps because you are a student writing essays for a university course). Imagine that you speak the dialect of English you were raised speaking, but that when you write in a formal context you have to us a register of English located somewhere between Shakespeare’s sixteenth-century language and that used by Chaucer in the fourteenth century. Imagine that this is normal and expected, and that people are taught how to write in this elevated linguistic register as a normal part of their education.

When writing formal literary Welsh today, people use a linguistic register which is based to a great extant on the 1588 Bible produced by William Morgan. And one of things which made (and makes) William Morgan’s Welsh such a powerful, elegant and flexible literary idiom is the fact that it was influenced to a great extent by the formal language of the medieval Welsh bards.

Artistic arsenal

This means that if you write creatively in Welsh, you have a huge range of literary registers in your artistic arsenal. You can locate your work on one far end of the long linguistic continuum and use formal literary Welsh. Or you can go to the exact opposite end of the continuum and write in an extremely oral fashion, using writing to express how people speak a particular dialect. Indeed, this later stylist choice has helped create some great Welsh novels, from Caradog Prichard’s 1961 classic, Un Nos Ola Leaud, to Robin Llywelyn’s 1992 hit, Seren Wen ar Gefndir Gwyn, to novels published during the last few years. We might locate BBC Welsh somewhere between the middle of the continuum and the linguistic end and the language one tends to find in a periodical like Golwg somewhere in the middle. And, of course, a creative writer can run different registers against each other productively, mixing them to whatever artistic ends suit the project.

Uniformity

As discussed in previous episodes of the podcast, the Bible was published in Welsh because of the fact that Elizabeth I and her government wanted to enforce religious and political uniformity in her realm. Thus a drive to homogenise England and Wales religiously also provided the Welsh language with new foundations. William Morgan’s Bible was used during church services, and, as everybody was legally obliged to attend church, people all over Wales absorbed large doses of this elegant and elevated version of their native language every week. This proved extremely important in terms of Welsh national identity, as Welsh speakers, unlike speakers of many other minoritized languages, had a default literary language to unite them. Welsh people have found plenty of other things to argue about throughout the centuries, but, unlike Irish or Breton speakers, they have not argued about what dialect should be used as an official literary language.

Achievement

The significance of William Morgan’s linguistic achievement was recognized by contemporary Welsh literati. Writing 1595, Morris Kyffin described the 1588 Bible as gwaith angenrheidiol, gorchestol, duwiol, dysgedig (‘an essential, magnificent, godly, learned work’). In a cywydd addressed to William Morgan, the poet Rhys Cain adapted the centuries-old mechanisms of bardic praise to highlight the significance of the 1588 publication. After first stressing the importance of the translator’s Cambridge education, the bard reminds us that William Morgan translated the Bible from the original Hebrew and Greek:

Chwilio Ebryw’n wych lwybraidd,

Chwilio’r Groeg a’i chael o’r gwraidd[.]

‘Examining Hebrew brilliantly and methodically,

Examining the Greek and getting it from the source.’

Rhys Cain then provides a nice versified description of the translator’s talents and the resulting success of the translation:

Medraist drin y doethineb,

Mynd trwy nod nis mentrai neb;

Cwrs dwyfol, c’weiriaist hefyd

Cymraeg iawn i’r Cymry i gyd:

Rhoist bob gair mewn cywair call,

Rhodd Duw, mor hawdd ei deall!

‘You were able to treat the wisdom [of the Bible],

Achieving a goal nobody else could venture [to achieve];

A godly pursuit, you also established

Proper Welsh for all of the Welsh people:

You put every word in a sensible register,

God’s gift, so easy to understand!’

Here we have that noun, cywair, still used in Welsh to describe ‘a (linguistic) register’, as well as a conjugated form of the verb cyweirio, ‘to establish (a linguistic register).’ It is truly wonderful to have a contemporary poet praising William Morgan for doing exactly what we – with hindsight accumulated during 436 years – can see clearly. The 1588 Bible established a proper Welsh linguistic register for all of the people of Wales.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.