Foreigners Everywhere: A triumphant Venice Biennale

Tony Curtis

This year’s Biennale was focused, as far as any Venice Biennale is focused, on the theme “Foreigners Everywhere” curated by Adriano Pedrosa, the first South American to do so.

As always, there is the Giardini site, which has the main National pavilions, the Arsenale which has a huge variety of individual artists and other nations, and finally the many Collateral Events which have to be tracked down in the confusing maze that is the city of Venice.

It would be impossible to sum up the disparate parts of any Biennale, thus my account will be incomplete and partial.

For “Britain” read “England”

The British Pavilion is one of the founding establishments and this year features the work of the film-maker Sir John Akomfrah whose work is “Listening All Night to the Rain”.

This artist whose focus has been so often on the colonial past of Britain and re-imaginings of experiences and shifting identities, has shown very widely: I have seen his work in the Arnolfini in Bristol and in the Artes Mundi Prize in our National Museum, which he won in 2017.

In 1961 one of the three featured British artists in the British Pavilion was Ceri Richards, surely the most significant painter from Wales in the mid twentieth century; his monumental “Cathédral Engloutie” paintings are among the finest works ever produced by a Welsh artist.

Richards won the Giulio Einaudi Prize that year. No solo artist from Wales had featured in the Biennale until the establishment of a Wales pavilion. The future of a Wales pavilion is uncertain, probably very unlikely.

An inclusion in the British Pavilion is even less likely: for “Britain” read “England”.

Of the four UK countries, Scotland, having exhibited for twenty years, has suspended its presence to allow for “a period of reflection and review”.

Northern Ireland’s Cathy Wilkes was the featured artist in the Great Britain pavilion in 2019, but there has been no dedicated Northern Ireland pavilion for fifteen years.

This year the Republic of Ireland has “Romantic Ireland” by Eimar Walshe in the Arsenale. This is a multi-track video installation which interrogates Irish identity through an operatic score based on words by De Valera, and deliberately clichéd characters from historical dramas.

That said, it simply does not work and the wearing of plastic balaclavas by the actors could well be taken for black-face by those who walk quickly through the space.

Still, it is an Irish presence. But there is no official presence from Wales. Cymru yn Fenis was last featured in the city in 2019 when the Cardiff-based artist Sean Edwards took over the Santa Maria Ausiliatrice with an installation that included a daily live audio link-up with his aged mother in Gabalfa where the artist grew up on a council estate in the 1980s.

Reservations

I had reservations with regard to this work (see the Wales Arts Review 26.06.19 website archive), but, nevertheless, was pleased to see a continuing Wales presence in Venice. The argument for representation is surely as vital as it was when this bold statement was made by the Welsh Arts Council:

“Wales’ presence at the Biennale gives a platform for visual art from Wales on the world’s most prestigious international stage. Benefits and opportunities are reflected back into Wales through the strategic commissioning of Cymru yn Fenis/Wales in Venice exhibition and related programmes; including Invigilator Plus, Travel Bursaries provided by Wales Arts International, educational resources as well as talks, events, links, and where appropriate, a re-staging of the exhibition produced for the Biennale back in Wales.

“The Venice Biennale is critically important for the profile, reputation and future careers of artists selected to represent Wales and for the image of Wales as a country that seeks to promote its contemporary culture worldwide, distinguishing Wales’ cultural profile with high quality art. The exhibition from Wales is commissioned and managed by Arts Council of Wales with support of grant in aid from the Welsh Government.

“The partnership between the Arts Council of Wales and Welsh Government is an excellent example of how we work closely to achieve our vision of Wales as a culturally vibrant nation. In a devolved Wales and at a time of great economic constraint, it is vital that the country’s creativity continues to register on the world stage.”

Laudable

That was and remains a highly laudable aim. Cerith Wyn Evans was the first featured artist from Wales: in 2003 he sent a searchlight beam into the night sky from the island of Guidecca. In an abandoned brewery, the Birreria, Wales presented four successive Biennale exhibitions.

In 2005 the outstandingly inventive and witty Laura Ford showed her “Dancers” and the “Glory Glory” national costume figures very much pre-figuring this year’s Shonibare work, and in 2007 Richard Deacon was included. The celebrity box was well and truly ticked when John Cale was featured in 2009.

His “Dark Days” explored the sounds and images of a post-industrial Wales. In 2011, Tim Davies’s ambitious plan to swim down one of the canals was cancelled after he injured himself and we were left with a gondola trip and his hand trailing in the water.

In that year Wales relocated to the Santa Maria Ausiliatrice in the Castello area, between the Giardini and the Arsenale.

The new venue attracted 30,000 visitors across the six-month exhibition period, surely justifying the considerable expense involved in the project. Clearly, that money is no longer available and one wonders whether, following the “period of reflection and review”, it will ever be again.

Difficulties

So, Wales, like Scotland, has decided to have “a period of reflection and review”. Of course, organising, staging and curating work for the Biennale, is an expensive commitment.

With our leaking national institutions, protesting singers at the WNO, St. David’s Hall RAAC-ed with pain, publishing and performance facing deep and possibly irrevocable cut-backs, “distinguishing Wales’s cultural profile” is proving to be extremely difficult.

Having said that, there are presences in Venice this year representing distinctly smaller nations – indigenous artists from the Pacific – Maori, Tongan, as well as countries who have not shown before – Ethiopia, Benin, Senegal and Panama.

There is even an artist from Palestine. Nations who must be facing much worse economic and social challenges than we are in Wales, are nevertheless present in the 24th Biennale. In my Arsenale section, you will see work from Lebanon.

The Arsenale

The first work to welcome one into the vast sprawl of the old naval arsenal – The Arsenale – is Refugee Astronaut by Yinka Shonibare CBE RA, another British artist this year at Venice. Through this summer he has had an exhibition in the Serpentine Galley in London – “Suspended States” in which historical figures from British history – Churchill, Kitchener, Queen Victoria – are re-configured; there is also a library and other images are re-worked to include references to our colonial past by covering them with brightly colourd patterns.

He explores the cultural connections and tensions between Britain and Nigeria. Rather than destroying statues, he is re-purposing them by covering the original marble with bright, energetic African designs.

In The Arsenale, Shonibare, who is wheel-chair bound and directs a team of assistants, has recreated the figure of an astronaut who strides towards us. His figure, again, is dressed in colourful African designs.

He carries on his back an oxygen support system, but also the detritus of Western colonialisation. It perfectly and succinctly embodies the Biennale’s theme of otherness. Appropriately, Shonibare is also featured with other artists in the Nigerian pavilion in the Dorsoduro with his “Monument to the Restitution of the Mind and Soul”.

Outside, on the main quayside are positioned imposing totemic columns. The American Lauren Halsey from South Central Los Angeles has Hathoric columns with the features and stories of her community. Their imposing height and prominent position draw you towards them.

Then you begin to encounter the specific faces at the top of each; then the incised details of elements of her community.

Like the Trajan Column in Rome, you are not going to be able to follow the complete and varied narrative, but you pass on having been given an insight, an introduction to the multifarious aspects of her Bro. It is a much more impressive offering than that of the official USA pavilion. As we shall see.

Halsey, 37, is in her prime as an artist and has an exhibition “Emajendat” opening in November in London. She was featured in the Observer’s arts section on Sunday 27th October in a profile by Kadish Morris “Straight outta South Central”.

The show in the Serpentine South Gallery is “an immersive funk garden” inspired by Parliament sister group Funkadelic. Complete with face piercings and baseball cap, Halsey is the black politicised, feminist celebrant of her folks. “Funk is oxygen. It’s life.”

In 2020 she founded a community centre, Summaeverythang, that produces and donates organic produce to her people. She says, “We can only save ourselves”. In the middle of a Trump nightmare, that can only be a beacon of hope.

Back inside one encounters Brett Graham’s: Wastelands,2024. He is part of a contemporary Maori art movement and his large hand-cart with its outstretched arms appearing to plead for your attention, is filled with the eels that were a staple diet for his community and which are so threatened by climate changes and human interventions in his region.

It is an effective placing in the remains of this huge workplace, a rural, traditional vehicle parked between the columns of the ordinance factory.

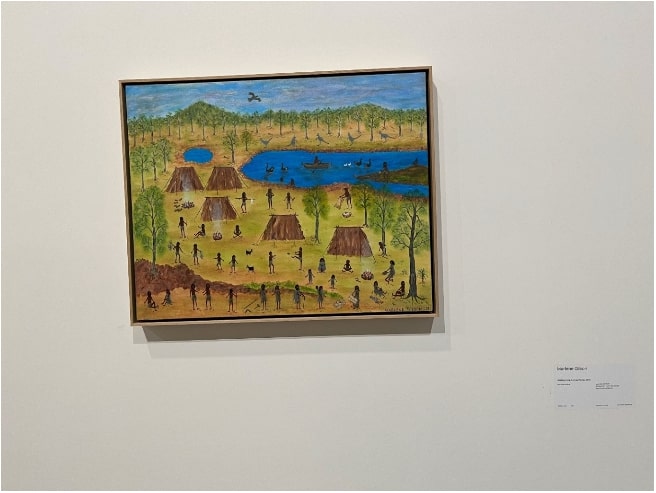

Most of the works in the Arsenale, in fact most in the Biennale as a whole, are works of three dimensions or video installations, but there are some notable exceptions. The Australian artist Marlene Gilson has re-visited C19th colonial portrayals of her indigenous people and re-considered them.

Marlene Gilson is an elder and traditional land owner. Thus, she is empowered to engage with what might be questionable depictions of her people. They are certainly convincing versions of the sort of pictures that were produced by early settlers, whether they were convicts or the military.

Australian and New Zealand art is strongly represented this year. As we shall see in the Giardini.

Bárbara Sánchez-Kane’s Prét-á-Patria is From Mexico and draws most attention in the LGBTQ section. Her skewered marching men are revealed to have women’s underwear beneath their uniforms. There were actors in these costumes for the opening event apparently. It’s a witty comment on the macho military. A show stopper.

Lebanon has Mounira Al Solh’s A Dance with her Myth. An example of the effectiveness of juxtaposing painted works and an installation of considerable size.

The boat, or skeleton of the boat, invites us to take a journey onto the imagery of the hangings. The aim is to re-consider the myth of the abduction of Europa. “Few people know that Europa is Phoenician,” the artist argues. This room has a welcoming organic feel and a narrative, that is not always the case in the Arsenale.

There are also paintings by Patricia Abad of the Philippines and the USA. She is a first-time exhibitor.

These are vibrant mixed media works which bring together the cultures which define her life narratives and locations. I was thinking: Shani Rhys James, Sue Williams, Lois Williams or the emerging Meinir Mathias should be here.

THE GIARDINI

In the Giardini area for the official national pavilions we headed first for John Akomfrah, an artist and filmmaker whose work is an investigation into memory, racial injustice, the experiences of migrant diasporas and climate change.

Listening All Night To The Rain continues the artist’s preoccupation with themes of post-colonialism, ecology and the politics of aesthetics with a renewed focus on the act of listening and the sonic. The exhibition, entirely in darkened rooms, is seen as a manifesto that encourages the idea of listening as activism and is conceived as a single installation with eight interlocking and overlapping multi-screen sound and time-based works.

Bodies of water are a central motif in Akomfrah’s exhibition and form a connective tissue that holds the many layered visual and sonic narratives together. Together with the sonic, Akomfrah explores the role of water in understanding our world and holding our memories.

Open-ended in structure, the exhibition is reflective of the artist’s abiding interest in non-linear forms of storytelling and collage. The exhibition probes into the ways in which addressing and connecting vast historical narratives across five continents can then be reflected in the experiences of diasporic people in Britain and in the faces of post-war black Britain.

There’s nothing explored here that we have not seen in previous exhibitions by this artist. Perhaps what he wants to say will bear repeating. Though the ecological arguments have been more powerfully expressed in the whaling sequences of his Artes Mundi winning work in Cardiff.

In other rooms of the British Pavilion, Sir John Akomfrah celebrates “Rachel Carson”. These videos move the argument forward to include climate threats as well as entrenched prejudices.

The whole pavilion is made into a darkened space this year: nothing of the gardens or the wider colours of Venice are allowed in. It is a serious and challenging use of the old building, one of the first to have been established in the Biennale. That said, one knows what to expect from this artist and there are no surprises.

Some years back I would look forward to sitting and taking stock on one of the wooden seats on the British Pavilion’s verandah. These were designed by the Welsh/Belgian artist Sir Frank Brangwyn. If they have been permanently removed, perhaps, like his unwanted House of Lords murals now housed in Swansea’s Brangwyn Hall, we could have these shipped to Wales?

Sir Frank Brangwyn, a regular visitor to and engraver prints of Venice, is no longer present, but other Belgians are. Their national pavilion in the Giardini is a particularly interesting one this year. Large folk-lore figures sourced and suggested by various regions have been constructed and shipped to the city.

Beginning in Leuven and wandering as far west as Pamplona, by road and boat the giants, conceived and constructed by seven artists, have travelled to Venice.

The journey has involved many people, adults and children; recipes, performances and commissioned music. The whole exercise was recorded on video and is accompanied by a free pink trilingual newspaper distributed in their pavilion. “Petticoat Government – l’petti lion”.

It’s Jeu Sans Frontier out of the school of the Eurovision Song Contest. Iconoclastic, exuberant and bonkers, quite bonkers. But irresistible, if you can discount the money they must have spent. The pitch for funding from those artists/curators must have been straight out of Monty Python. And Wales is worried about money…

The seven giants take their places on an aluminium structure. And you enter to the noise of clogs and drums of a carnival procession, some sort of a European cultural heritage.

The claim is that “Giants reflect our desire for hyperbole. In their travels, the Giants changed their scale – facing the Alpine mountains, at the foot of a bell tower in Padua, in front of a dancing child in Mons – they all confirmed the theory of relativity.

Carnivals are great moments of disruption of the social and political order, when assigned positions and roles are suspended – the cobbler becomes king and the dishwasher becomes queen, and vice versa.”

Well, yes. If you then throw in recipes, a version of a Tarot pack, photos, a map, drawings, sketches and menus.

Oh, and a picnic on a frozen lake in the Alps with all seven giants. Many members of various communities participated and there was clearly an inclusivity to the whole exercise. Finally, it was convincing fun and involved many people in the art process. Venice can seem very elite: this wasn’t.

The textile creation and re-working of Nordic myths was almost worth the annoyance of negotiating the bamboo obstructions. In the Arsenale we had braved an even more forbidding structure of scaffolding poles and obstacles in the Italian space after which one was encouraged to sit around a bubbling and plopping pool of what (I hope) was caramel.

One is left with the suspicion that these spaces cannot be filled by effective art-works and that the structures are there as space-fillers. This was not the case with the Belgian giants underneath whose presence one enjoyed walking.

The USA has usually a strong presence in the Giardini, but this year’s was rather facile. The featured artist was Jeffrey Gibson who claims descent from the Choctaw Indians. He has an MA from the Royal College of Art.

His work uses a “hybrid visual language which draws from American, indigenous and Queer histories with reference to popular sub-cultures.” All the bases are touched here, then. Unfortunately, it’s a mess and becomes just silly.

The pavilion has an amorphous set of lumpen shapes at the entrance upon which one is urged to refrain from climbing. Then the rooms display various shapes, poles and creatures which are garishly dressed in beads. All of which is to dispel what Gibson claims is our general “chromophobia”. His pavilion gives us plenty of colour, but precious little purpose.

The clichés are exemplified by the figures and the walls. In comparison with other American artists in Venice this year, Gibson’s work is simply not up to this national exposure. He fails to engage in the same way that fellow Americans Halsey, Indiana and Fratino achieve in Venice this year.

The France pavilion is usually a high point of the Giardini, but this year it fell short, sort of trying too hard with its flashy mammoth video screen of shape-shifting statuesque figures. Inside, there were more screens and a bewildering maze of ribbon, wool and textile shapes hanging from the ceiling.

The artist this year was Julien Creuzet, of French-Caribbean heritage, who was born in France but raised in Martinique. The curators claim that, “his singular work and his gift for oral literature feed on creolization by bringing together a diversity of material, stories, shapes and gestures.”

The problem was that the visual and aural effects were never focussed for the visitor. Well, not for this visitor, anyway. At the previous Biennale France was represented by Zineb Sedira, an artist of Algerian descent: France is sending out the right signals after being exclusively a showcase for white artists. It’s shame that this year didn’t gel. Lots of sound and weirdness, but to no clear purpose, I thought.

In contrast to a space, focussed and pertinent offering in the Australian pavilion.

We queued for half an hour to get in to this pavilion. That’s the prestige of the Golden Lion Prize. The wait was worth it. Two Australian men engaged us in conversation in the line and were excited to see the Archie Moore.

What Moore had done with the large, darkened pavilion was to fill most of the floor space with an enormous table on which were placed neat piles of A4 documents. These were the redacted accounts of the trials of indigenous people in the Australian courts. Many had died in custody.

No matter how far one leaned in, it was impossible to read these in any real sense. The table stood in a tray of black ink and water, so one risked falling over in to this dark moat.

All the walls were, in effect, blackboards on which Moore has written with white chalk the names of his people. Disappearing into the gloom of the ceiling were the colonial and derogatory given names of the black folk “Jimmy Boy”, “Big Black Fella”.

The names became more anglicised and began to include family names as the chalk remembrances came lower down the walls. It was a powerful enactment of the colonial theft of identity through language. On paper and on the walls, it was a challenge to locate and record the lives of the indigenous people, even when they became subjects of the enforcement of laws.

Moore is 54 and from Queensland where his mother was Aboriginal and his father of British descent. His previous work has included the building of indigenous brick huts and in 2021 he exhibited in the UNSW gallery a conté crayon backboard.

On the basis of such work, he has been given this international showcase in Venice and is surely going to exhibit very widely from this point. This installation should come to the UK.

Politicisation

Protest, polemic and politics is the stuff of every Biennale this century, but the politicisation of the actual pavilions which has traditionally occupied the Giardini has never been so marked as in 2024.

The pavilions, in any case, reflect an old politics and power bases. This year, the Russia pavilion is occupied by Bolivia.

And, as you would expect, the Israel pavilion is far from normal, the space has been voluntarily closed by the chosen participating Jewish artists. They are refusing to share their work until a cease-fire is agreed. It has remained closed and closely-guarded for the duration of this Biennale.

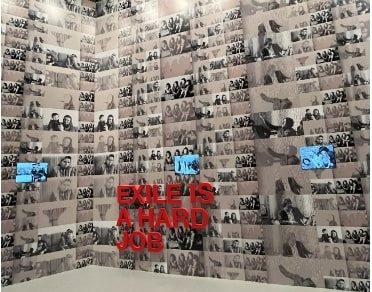

The Central Pavilion, personally curated by festival director Adriano Pedrosa included some of the most powerful political art, though. There was a film and photographic display based on Puerto Rico which was a revelation.

This “rich port” (in Spanish) is a self-governing Caribbean archipelago, a “Commonwealth” of the USA. Also, a photographic and video wall based on immigrants to France. If only Donald Trump could be taken to the Biennale, but that’s an absurd idea.

There is also a rising star of the New York art scene: Louis Fratino, at thirty, is already seeing his paintings nudge towards the million-dollar mark in auction houses.

He is a free, luscious painter of, mainly, gay men. An indoors Hockney. It’s obvious that he is another artist we will be seeing more of in the UK.

Finally, across the canal that splits the Giardini was the Romanian Pavilion with actual paintings by Serbam Savu reflecting displacement and homesickness experienced by those who migrate for work.

This was a large selection of well-executed works which created an impressive wall you walked past and returned to. Just paintings: but they have a point to make, narratives to deliver. Quietly, demanding your attention.

The Wider City and the Collateral Works

We have been located in the Cannaregio area of Venice for the last three visits. This is the sestieri in which the Ghetto is located.

This is the very original coining of the term and the creation of a specific area for Jews which the ever-pragmatic Venetian merchants and Doges conceived to accommodate their sometime unwelcome, but always essential Jewish Venetians.

It is a very constrained little island, a former iron-works (from which “Ghetto” is coined). You can go on a guided tour which is fascinating. There are kosher eating places and moving commemorative wall for the victims of the Holocaust. We did not re-visit this year.

Across the street from our apartment in the Cannaregio – the Romanians made use of an empty shop in which participants could re-assemble version of the paintings in the Giardini using tesserae. It’s the Biennale on the street.

This was set up in an unused shop on the Strada Nova, a few hundred yards from our apartment. This is a major thoroughfare and a fine place to exhibit. Might that arrangement be a possibility for Wales to explore in 2026? Some presence is surely better than none.

One of the most prestigious and breath-taking Venice venues for the collateral art works is San Giogio Maggiore, one of the most painted and photographed parts of the city. Ment’s works are particularly prized and may be seen in our own National Museum.

This vast church floats on its own island across from St Mark’s Square and connected to the Giudecca. In previous Biennales we have seen significant works by Sean Scully, Anish Kapoor and Jaume Plensa. This year it is the Belgian artist Berlinde de Bruyckere with her “City of Refuge III”. She was featured in the Belgian Pavilion in 2013.

De Bruyckere has exhibited in the UK at the wonderful Hauser and Wirth farm-gallery in Somerset (2019). She is a mid-career artist from Ghent whose father was a butcher. She does not shrink from depictions of death and body parts. Often, she uses casts from body parts, layers of animal skins and blankets sourced from charity shops.

She appreciates the lived-in quality of such things. “Because of that, you feel the body even though not seeing the body.” Here, she is inspired by the story of St Benedict, torn by thorns to overcome his carnal desires.

The great church is a perfect place to show this work; it occupies the space as if it were its own. The stark imagery of her pieces resonates against the great paintings and sculptures commissioned by the Church over the centuries. Her sections of torso have the power of saintly relics.

Her reference to skins reflects her experience of visiting an abattoir, “…the men scattered salt on the skins in a sowing-like motion. Nowhere Have I experienced life and death as closely as here, Eros and Thanatos”.

This work in this setting alone justifies the trip to Venice. I look forward to seeing her again in the UK. She is a major artist

From the sublime to the materiality of commerce.

We are always in Venice for the art, but invariably, also visit our favourite department store – Fondaco Dei Tedeschi. This is a huge former post office and trading exchange next to the Rialto bridge. It is a high-end and designer place where few items display prices: if you have to ask, you can’t afford.

During the Biennale, the Tedeschi hosts an exhibition, usually on its top floor, where you can also step out on to the terrace for one of the great views down the Grand canal. That terrace was closed on this occasion, but there was an exhibition of large photographs by Lee Shulman of period American vacations. These were caught between irony and nostalgia, with the washed-out Kodachrome colours and faded fashions of another era. In this palace to conspicuous consumption, they were given added meaning.

Shulman’s “The Anonymous Project” is an exnormous collection of the slides and emories of others. Shulman was born in London in 1973 and now lives in Paris. He collates sourced and donated slides and curates his exhibitions from these. One cannot imagine any of the holidaymakers he depicts being able to shop for anything in the Tedeschi.

Throughout the city there are posters and reminders of the Indians exhibition. The American artist Robert Indiana (1928-2018) has a partial retrospective in Procuratie Vecchie in Piazza s. Marco: The Sweet Mystery. Some of these works have already been shown at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. Robert Clark re-named himself after moving to New York City in 1954, and in regard to his adoptive parents back in that state. Here he established a precarious existence in an old loft in lower Manhattan, suggested by Ellsworth Kelly.

He became involved with Andy Warhol and was filmed by him. With no money to establish himself in a conventional studio, Indiana used the discarded ship’s masts and other detritus of Coenties Slip, which had been an industrial part of the city. Artist and writers occupied spaces here for over a decade.

Educated courtesy of the GI Bill, he had been at the Chicago Institute of Art and later spent a year time in Edinburgh College of Art. He is best known for his playful and profound re-presentation of letters and numbers, none more so than his LOVE sculptures.

The totemic former masts are strange and quirky and affecting, more so, for me, than the configurations of numbers. Though I wish I had seen them in the Yorkshire context too.

Apart from the two very substantial grounds for national and officially curated artist, there is art just about everywhere throughout the city. The C18th Palazzo Diedo right next to our apartment in Cannaregio was staging the JANUS works while being renovated.

The Berggruen Arts and Culture foundation clearly has a large purse and while engaging in the renovation of this vast Palazzo, is hosting a number of interesting artists who variously respond to their particular surroundings.

Upon entering, one encounters layers of history and decoration.

And the work continues through the staging of the exhibitions and, indeed, underneath and alongside new works of art.

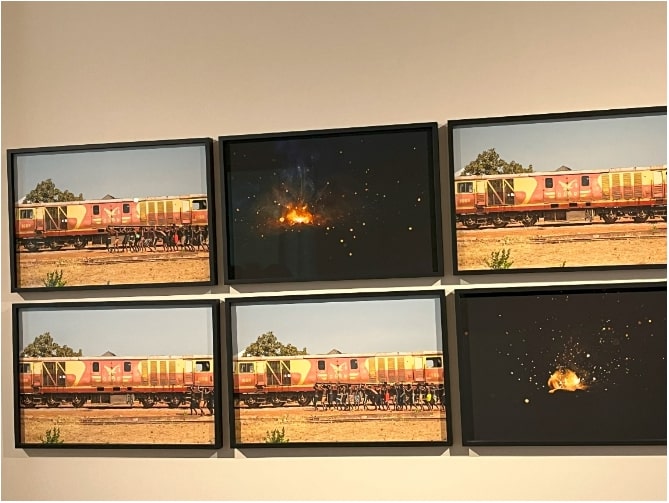

This railway-themed room was especially effective. Photographs complementing the three-dimensional re-workings of the ceiling by Sugimoto. The way in which railways were instrumental to the colonising and later development of nations, and the essential function they still have in those counties and the opportunities they provide for expansion and economic survival.

More portentous and less convincing was the room showing “A Prayer for World Peace” by Mariko Mori of the Faou Foundation. A glass crystal was the focus of the installation. This was “a sacred jewel signifying Buddha’s greatness and virtue”.

The jewel would be taken at the end of the Biennale to be deposited in a cave in Ethiopia, the birthplace of humanity. It might be supposed that the poor Ethiopians might have other priorities. Still, Mori is highly regarded in her native Japan and has laudable ecological principles. Her work has been installed across six continents.

This foundation and its featured artist also showed a large “Peace Crystal” at Palazzo Corner Della Ca’Granda, but this had been removed the week before our visit

To put all this contemporary art into context, a visit to the Scuolo de Rocco and The Frari is a reminder of why and how Venice became one of the great centres of European culture. Unfortunately, the enormous Tintoretto Crucifixion was inaccessible because of restoration work, but there was plenty more to see, including this stunning work leaning against a wall in the Frari. You look up to see its place in the ceiling to which it will be shortly returned.

Venice is an old city built precariously on a swamp and marshes. It is constantly working to preserve its buildings, its heritage and its integrity. Yes, it can sometimes and in some places resemble a building site; yes, there are far too many people visiting, but if one avoids the obvious congestion of St Mark’s Square, uses the Vaporetti sensibly and eats with the locals away from the tourist drags, then it has plenty of charm and intrigue.

They have legislated against the monstrous cruise ships and there is now a tourist tax for day trippers. The former were almost certainly jeopardising the structure and survival of the old building; and as for the latter, why would you visit this unique city for just a day?

Waiting for the Aligaluna boat to take us back to the Marco Polo airport, we got into a conversation with three Americans who were over for a PR conference. In common with most of the Americans we encountered, they were embarrassed by the awful state of their country and the dark clouds of its coming elections.

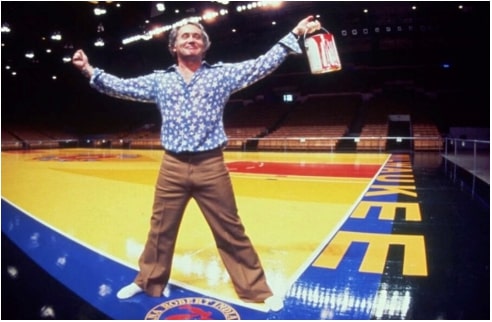

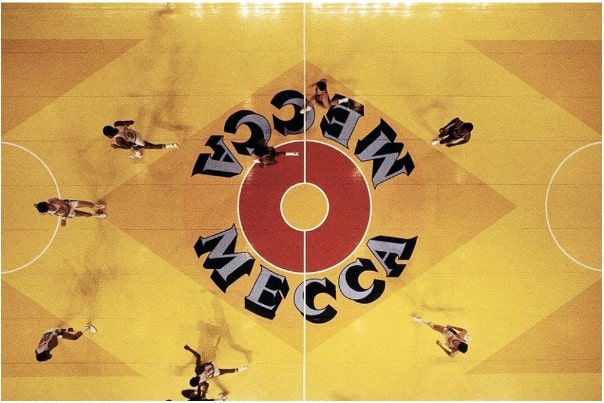

However, when I mentioned the art we’d seen – the silly American Pavilion and the fine Robert Indiana retrospective, one of them lit up – “I’ve met him – Robert Indiana – in our city, Milwaukee. It was years ago when the firm I was working for stepped in to save the basketball court.”

What on earth was she talking about? Well, if you search online for Indiana and basketball court you have her account verified. The artist was commissioned to design a court for the city’s NBA team. Years later, when they moved to a bigger stadium, the court was to be ripped up and discarded, until the business this woman worked for stepped in to save it. Hung now on a gallery wall, it is larger than the Frari’s Tintoretto.

That encounter on the Alilaguna was a final reminder that art and commerce, vision and energy will triumph. It is a principle that we in the arts in Wales seem to have forgotten. If the Arts Council is too poor, if the Senedd can’t find the money or enthusiasm, then is there no commercial concern in Wales which would see the support of a Wales presence at the 2026 Venice Biennale as not only relevant and prestigious, but also as good business?

Tony Curtis is a poet and novelist who often writes about art. His latest collection, Leaving the Hills, has a number of poems based on contemporary art and photographs. His two books of interviews, Welsh Painters Talking and Welsh Artists Talking were notable contributions to the appreciation of the visual arts in Wales.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.