Belgium marks 80th anniversary of the liberation of Brussels by Welsh soldiers

Luke James, Brussels

The streets of central Brussels were almost deserted when, at exactly 7pm on Sunday 3 September 1944, a tank appeared on the city’s main thoroughfare, the Boulevard Anspach.

The tank’s crew, five soldiers of the Welsh Guards, had just completed an almost 100-mile advance during a single day despite facing repeated attacks by German forces along the way.

Their arrival brought to an end four years, three months and sixteen days of Nazi occupation of the Belgian capital. Five minutes later, hundreds of people poured out onto the boulevard.

“When the first tank arrives in Brussels the streets are empty because the idea was not to present a danger for the troops that are coming,” said Chantal Kesteloot, author of ‘Bruxelles, ville libérée’.

“But very quickly the information circulates and people come to greet them. The soldiers said they didn’t know what was more difficult: the fact that they could meet some Germans who were still there, or the fact that people were so enthusiastic about their arrival.”

The people of Brussels had been waiting anxiously for the arrival of allied troops since hearing about the Normandy landings in a special BBC radio broadcast on June 6. They were even more eagerly anticipated after the liberation of the French capital in late August.

“Yesterday Paris, tomorrow Brussels,” read the headline of the August 24 edition of Le Peuple, one of the many clandestine newspapers published by resistance groups.

Surprise

The timing was though a surprise to the Welsh soldiers who took part.

After liberating the town of Arras in northern France on Friday 1 September, the Welsh Guards had expected to be given the weekend to “perform maintenance upon our long-suffering vehicles and to rest ourselves,” according to the diary of Lieutenant Colonel JC Windsor Lewis.

Instead, they were ordered by General Aldair to support paratroopers in capturing Brussels.

When bad weather made air operations impossible, the responsibility fell solely to the Welsh Guards and the Grenadier Guards, who took two separate routes towards Brussels.

“It became a bit of a race,” said Guy Bartle-Jones, a Lieutenant Colonel of the Welsh Guards, who will represent the regiment at the commemoration of the 80th anniversary of the liberation in Brussels on Tuesday.

“Both faced some resistance in various villages along the way. But the Welsh Guards had newer Cromwell tanks, which meant that they could achieve speeds of up to 50 kilometres an hour, whereas the Grenadiers had Sherman tanks that were a bit slower.

“In fact, in front of both the Welsh Guards and the Grenadiers were Household Cavalry reconnaissance squadrons. They were actually leading us down and every time we hit a bit of resistance, we’d have to stop and mop up.

“It was the same for the Grenadiers. I think they hit some resistance just outside Brussels which slowed them down and allowed us to have a clear run into Brussels. It was one of the longest armoured advances ever achieved.”

‘Terribly young’

The commander of the first tank to enter Brussels was 22-year-old Lieutenant John Dent, who was serving alongside his cousins.

“They were all terribly young,” said his son, Rafe, who is among the families of Welsh Guards soldiers who will take part in Tuesday’s commemoration.

“They didn’t say anything for years and years. It was the highlight of their lives but it also must have been terrible.

“One thing he always emphasised is how fast they were going. Speed was of the essence. You can’t hit a tank if it’s moving.

“If any of them stopped, they were picked off. There was no way they could steer them or stop them. But it meant they didn’t get hit.

“And that’s why they went quite so fast and ended up in Brussels ahead of the game with the Germans still there.”

The Nazis, who first occupied Brussels in May 1940, had already begun fleeing the city by car, horse drawn cart or bicycle. Nonetheless, these were dangerous days for the residents of Brussels.

“The Germans start to leave around the 29th of August but some people are taken as hostages with them,” said Chantal Kesteloot.” There were more than 65 hostages killed in a period of six weeks.

“It’s really a strange climate because the last bombing of Brussels was at the beginning of August, so people are expecting liberation but, at the same time, they fear what’s going to happen.

“Until the very end of August and the first days of September there were still people who were deported. On the 1st of September there was a last train with women who were sent to Ravensbrück [concentration camp].

“It was a really difficult period for the people here in Brussels.”

The final pro-collaboration edition of Brussels daily newspaper Le Soir published on September 2 told its readers “the Anglo-Americans will pay for each kilometre with heavy losses.”

Instead, the speed with which the Welsh Guards reached Brussels caught the remaining German forces off guard.

The gestapo and their collaborators were still in the process of burning their records at the Palais de Justice, which caused a huge blaze in the iconic building.

The Welsh Guards were intercepted on the city’s outskirts by members of the resistance who helped Lieutenant Dent and his crew navigate quickly towards the centre.

En-route they twice engaged German forces, near the Parc du Cinquantenaire and at Place du Trone near the Royal Palace, and ended the day with around 700 prisoners.

But the regiment’s official history says resistance “came mostly from the eager Belgian crowds.”

Radio Londres, the BBC’s French-language service during the war, had broadcast a message calling on Brussels residents to stay indoors to help allied troops move through the city freely.

While the streets were empty when the first tank arrived in the city, it didn’t stay that way for long as grateful locals pressed flowers, fruit, drink or themselves on their liberators.

“One was left wondering which was worse – to be kissed, hugged and screamed at by hysterical women whilst trying to give out orders over the wireless and to control the direction of your tank; or to be free of the crowd and shot at by Germans who did not shoot straight,” wrote Lieutenant Colonel Windsor Lewis in his diary.

The excitement only grew the following day when members of the Free Belgian Forces, who had regrouped and trained in Tenby following the occupation of their country, arrived after having themselves liberated towns in northern France on their way home.

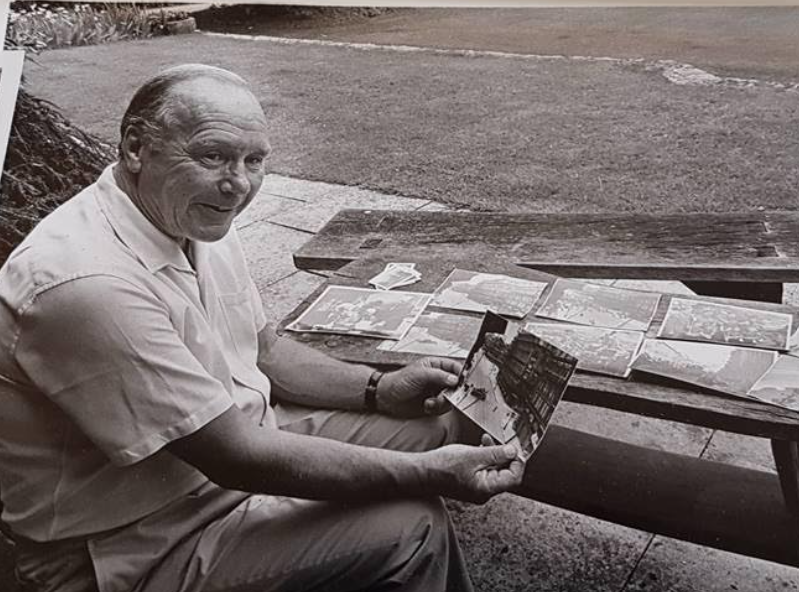

Welsh troops were naturally keen to remember the historic events. A notice was placed in one Belgian newspaper, La Dernière Heure, asking for amateur or professional photographers to send in any photos they had taken of the liberation so that “nos premiers libérateurs les soldats gallois” could “keep a memento of that memorable day.”

Back home, the press reported with pride that Welsh soldiers were first into Brussels. The South Wales Evening Post even suggested the first soldiers to enter the city were “greeted in Welsh.”

“It was a moving moment for two small nations who have always had much in common,” read the paper’s report on the liberation. “Belgium will never forget Wales.”

While the former claim is almost certainly an exaggeration, the latter is certainly not.

Ultimate compliment

The Welsh Guards were invited back to parade through Brussels on the first anniversary of the liberation and were also paid the ultimate local compliment, with the famous Manneken Pis dressed-up in one of their uniforms.

David Owen-Edmunds was among the Welsh Guards who maintained a connection with the city.

“My father spoke about September 1944 all his life, and maintained a lifelong fondness and association with Belgium,” said Tom Owen-Edmunds, who will be among the families of veterans represented at Tuesday’s commemoration.

“When we were growing up, he hosted the Belgian Admiral’s Cup sailing team at Cowes Week and we all had ‘Vive La Belge’ t-shirts which he printed. In his letters we found one from the lady he was billeted with, to his mother saying what a fine young man he was.”

The connection has been maintained over decades, even as veterans passed away, and on Tuesday’s 80th anniversary of the liberation, the band of the Welsh Guards will once again lead a parade through Brussels, passing a uniformed Manneken Pis on the way to the Grand Place.

“Through these commemorations, we bring to life the soul of Brussels, this city where the spirit of resilience and solidarity has never faltered,” said Philippe Close, the mayor of Brussels.

“We remember the sacrifices, the courage, and the unity that allowed our city to regain its freedom.”

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

The Cromwell tank not the Churchill…

A good read, at the same time the Florence Cooke was keeping pace supplying the Monitors with their massive shells and my uncle was driving a Diamond T tank transporter on the Red Ball Express…