Campaign launched to raise ‘forgotten Welsh hero’ from obscurity

Stephen Price

A campaign has been launched to rescue a ‘forgotten Welsh hero’ famed for being a cowboy, frontiersman, soldier and author from obscurity.

Back in 2020, George Owen from Rhyl was introduced to two books on Owen Rhoscomyl, authored by John Ellis and Hywel Teifi Edwards’, and was given an opportunity to see his grave, which George has said is in a very ‘sorry state’.

With George’s interest and appreciation of Rhoscomyl growing, the desire to see someone who has largely been forgotten by his own countryfolk became more urgent after seeing the Celtic Cross on the verge of toppling onto the other gravestone.

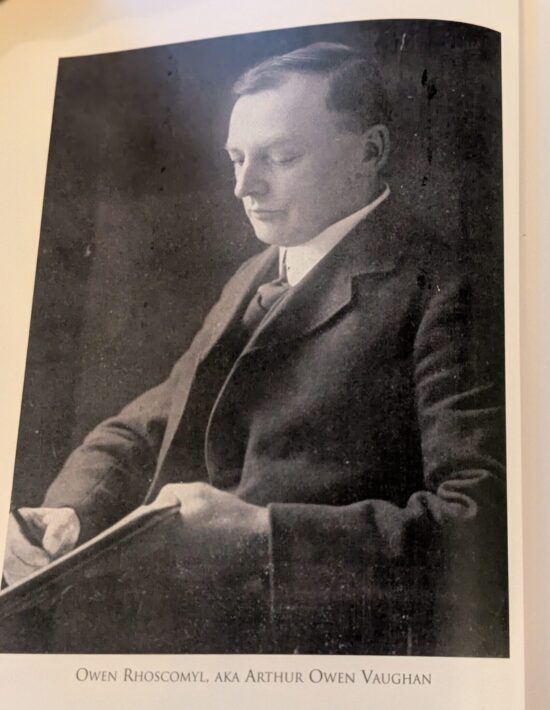

George Owen spoke to Nation.Cymru about his passion for Wales’ forgotten ‘hero’, sharing: “Who today knows of Owen Rhoscomyl, 1863-1919 or, as he was also known Robert Milne, or Arthur O Vaughan, DSO, OBE, DCM, Kings Own Yorkshire Regiment?”

He said: “Outside of the realms of academia I suggest he is a forgotten man.”

“Forgotten man”

Owen Rhoscomyl was a cowboy, frontiersman, traveller, soldier, novelist, historian and war hero.

In 2016 John S. Ellis , Professor of History at the University of Michigan-Flint wrote a well-written and well-researched biography on Owen Rhoscomyl.

Ellis wrote: “Around the turn of the century, Welsh readers thrilled to the heroic stories of Owen Rhoscomyl.

“Having been a cowboy, frontiersman, soldier and mercenary, Rhoscomyl was an adventurous and exotic as his stories.

“Roving the wilds of the American West, Patagonia and South Africa before finally settling in Wales, Rhoscomyl was a flawed hero who led a rough life that exacted a personal price in poverty, delinquency and violence. He identified deeply with the Welsh nation as a source of tradition, legitimacy and belonging within a wider imperial world.

“As a popular commercial writer of historical romance, imperial adventure, popular history and public spectacle, he rejected accusations of national inferiority, effeminacy and defeatism in his depictions of the Welsh as an inherently masculine and martial people, accustomed to the rugged conditions of the frontier, ready to advance the glory of their nation and eager to lead the British imperial enterprise.

“This literary biography will explore the vaulting ambitions, real achievements, and bitter disappointments of the life, work and milieu of Owen Rhoscomyl.”

Boyhood and the Wild West

Owen Rhoscomyl grew up in modest circumstances in Manchester and later in Tremeirchion, north Wales, where he was fed heroic Welsh tales by his Nain Annie.

But she passed away when he was 15, and seeking escape and adventure he boldly stowed away on a brig at Porthmadog en route to Rio de Janeiro.

Having picked up skills as a sailor during the voyage, he travelled down the US eastern coast, then, seeking further adventure, on the railroad he travelled to the American wild west.

He easily adapted to this adventurous life and, taking only three days learning to ride, became a cowboy herding cattle in Wyoming and Montana and, on this lawless frontier, had dramatic and bloodthirsty confrontations with native Americans and vicious bands of robbers. His letters home reveal exploits easily rivalling the best of Hollywood’s Westerns.

Army

After four years of this tough life, Robert Milne had experienced all the adventure a young man might need – “you didn’t meet many men over 50” he noted.

Thus, in 1884 he came back to the UK determined to put to work what he’d learned from his travels and his skills on the wild west frontier of the US.

In 1887, aged 24, following an unsuccessful effort to join explorer and journalist H M Stanley, who was planning an expedition to the Sudan (Stanley was from Tremeirchion, the same parish as Milne), he enlisted in the 1st Royal Dragoons.

His wild west experience made him well-suited to the army life. However, army recruits were generally an elite group from the well-off into which strata Milne didn’t easily fit and the social barriers and debts caused him problems.

His fortunes changed when he met Elizabeth Surtees-Allnatt, aged 71, a wealthy widow, scholar, successful author and campaigner.

She took him up, paid off his debts and encouraged his interest in history and writing. Life in the military had not developed as Milne had hoped and in 1890 Surtees-Allnatt bought him out of the Regiment.

She fostered his interest in literature and writing. His Nain Annie with her tales of heroic Welshmen combined with Surtees-Allnatt’s skills as an author, were two important influences that guided his future.

Novelist

Mentored by her he wrote several novels over the next few years under the non-de-plume Owen Rhoscomyl, which portray a variety of characters who were Welsh heroes who almost rival Bond in their exotic backdrop and quest for adventure, some based on his wild west experience.

He had a talent for writing exciting narrative and they were well-received in their day finding a ready market in the US, Australia and South Africa.

Boer War, Marriage and Patagonia

The Boer War provided his next sortie and, now in his 30s, he was in Cape Town the day before the Second Boer War was declared in 1899 with a new name Arthur Owen Vaughan.

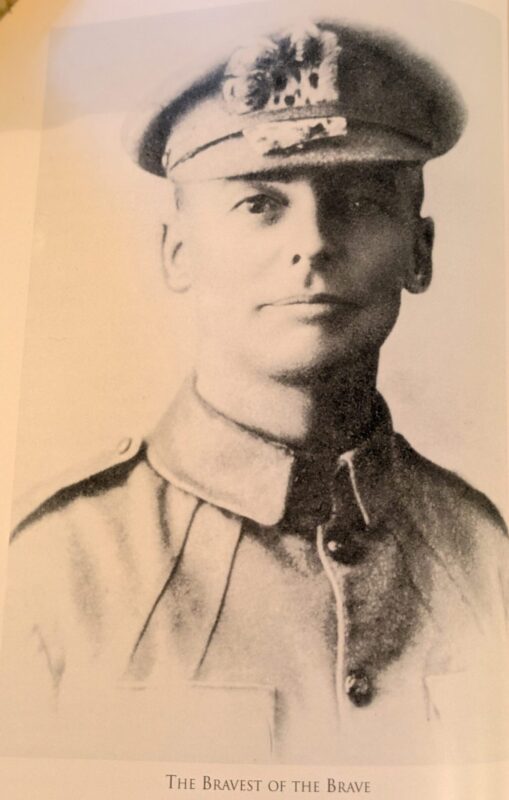

He joined a British force called Rimington’s Guides, a regiment of tough scouts. He found his place in this outfit and was three times praised in front of the army and thanked for his outstanding work; his superiors stated he was the bravest man they had ever met.

He rose to the rank of Lieutenant, and he clearly thrived in the wartime situation, was mentioned in despatches and awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM) in 1901.

It was at this time that he, now 37, met his future bride Katherine, a beautiful 19-year-old. She was from a wealthy Boer family and despite family opposition they were married in 1900.

The Boer war was an ugly and tough experience and had parallels with his wild west experience. In 1902 the war ended, Vaughan was discharged and with his wife he planned to travel back to Wales complete with a host of plots suitable for his novels and short stories.

Out of the blue he was asked to lead a plan to move the Welsh settlers in Patagonia from Chubut to the South African veldt. Chubut was a relatively inhospitable part of Patagonia and the plains of the veldt showed promise.

With his usual enthusiasm and application, he quickly put forward a plan for an area of the veldt suitable for a settlement and busied himself writing to the Colonial Office and Patagonian officials.

Though the plan was welcomed by the Chubut community it did not get support from the Colonial Office and as a result it failed and with it Vaughan’s hopes for some financial security.

None of Vaughan’s life experiences thus far had brought him any serious financial benefit.

Wales and World War 1

In Wales he fell back on his writing and raising a family, albeit in very modest circumstances, which the well-to-do Katherine was not used to.

In 1903 they had a son and eked out an austere life in Aberdovey, while Vaughan stretched their family finances travelling around trying to drum up support for his literary efforts.

Katherine suffered from ill-health and returned to South Africa for the birth of their daughter in 1904. Rhoscomyl left Aberdovey and lived in a variety of places around mid-Wales in very basic conditions almost like a vagrant.

Owen Rhoscomyl, as he decided he was now to be known, was inspired in his writing by what he saw as a lack of a history of the Welsh people and what had been written by English authors with a patronising viewpoint of the Welsh nation.

Rhoscomyl was trying to counter Celtophobia as expressed by Delaney, the Editor of the Times, who summed up the English attitude as follows: “the Welsh language is the curse of Wales . . . Welsh is a dead language. . . All the progress and civilisation of Wales has come from England.

Owen Rhoscomyl, harking back to his time growing up with his nain Annie, took a more heroic view based on nationalism and imperialism.

He carried out research and produced genealogies that matched with the clans of the Welsh princes. The clans of Wales were heroes far from the “loose twaddle about the Welsh being . . . trembling cowards who fled from the Saxons . . . they are descendants of a race of conquerors.” he proclaimed. This was set out in Flame-Bearers of Welsh History (1905) and was well received in certain quarters but not by of academic historians though it was used as a textbook in Welsh schools.

His books were a success and Rhoscomyl’s publisher wanted more. His friend, historian J Glyn Davies, when comparing his writing with his academic critics, wrote “none of them could write narrative like him; none had his literary gifts; none could approach his style”.

Despite his lack of formal education, he presented himself as a scholar working to establish a Welsh historiography, travelling around Wales giving lectures, studying genealogies and he became a popular speaker with his tales and strong opinions, always presenting himself at these events dressed in evening dress because the rest of his wardrobe was so threadbare.

This nascent literary success and financial promise brought his wife Katherine and his children back to Wales in 1905, though they were to live in a shanty-like existence in Arthog, Gwynedd, which would then have been a predominantly Welsh-speaking community on the Mawddach Estuary.

At this time , Rhoscomyl made frequent trips to Cardiff and became a regular contributor to theWestern Mail. He also wrote many historical articles in the Nationalist.

In 1909 Vaughan became a leading figure in the Legion of Frontiersmen, a forerunner of MI5 1913. There were frequent visits to London and trips abroad are hinted at, including Portugal, Bolivia and Peru. At this time he was befriended by David Lloyd George, and Lord Howard de Walden, a very wealthy aristocrat.

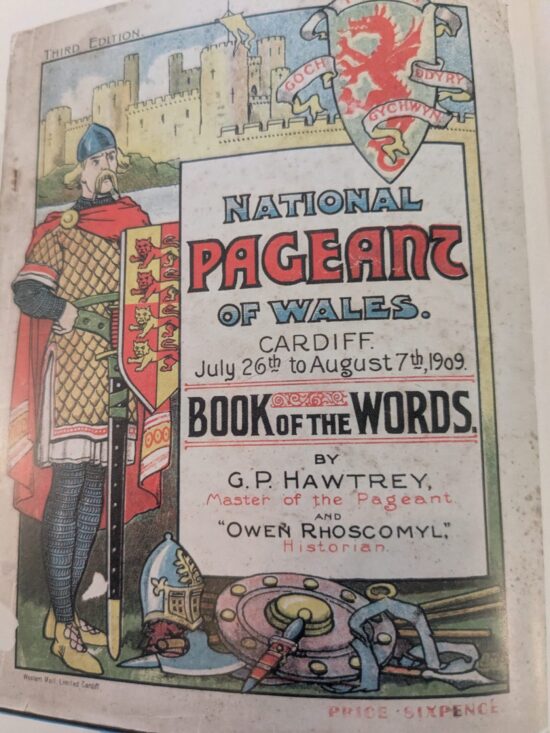

Promoted by Lloyd George, in 1909 he scripted the National Pageant of Wales in Cardiff, and in 1911 he scripted the Investiture of the Prince of Wales in Caernarfon Castle.

The family moved into a new semi-detached house in Dinas Powys. Living beyond his means was a constant problem and as a solution Vaughan dabbled in fruitless gold mining schemes in Honduras and he and Katherine travelled to the West Indies and central America.

Funds were always in short supply and Rhoscomyl had an unscrupulous approach to money dating from his wild west days and frequently tricked his friends to make ends meet, plus his fiery temper sometimes made family life difficult.

Lord Howard de Walden generously supported Vaughan’s work and de Walden also financed the provision of drama and theatre in Wales. Vaughan was very keen on this as it was in line with his nationalist ideas.

1914-1919. Vaughan had seen the war coming and he saw this war as his last chance of nationalist glory, and he recruited a Welsh Regiment of Horse based on his Boer War experience.

Supported by the Lord Mayor of Cardiff he raised 2000 men in two weeks and even managed to gain support from General Kitchener. Later he would lead the Cyclist Division; June 1915 was in action in France and was believed to be acting as Lloyd George’s spy carrying out secret missions to aid PM. I

n 1918 he was put in charge of 6000 men and promoted to lieutenant colonel. In 1919 he was awarded the DSO and, on Lloyd George’s personal recommendation, the OBE.

It was at this point that Vaughan’s health failed him and, in a private nursing home, aged 56, on 15 October, a month after his military discharge, he died of liver cancer.

He received substantial tributes in the press: the Western Mail’s obituary stated “he was a traveller, a soldier, an organiser, and an originator.” Lord Howard de Walden praised him as “the truest Welshman that I ever found in Wales.”

He received many similar tributes but perhaps because of the distressed postwar period his name soon faded. A subscription for a Celtic Cross was organised by the Western Mail but that waited until 1927 to be put in place and was largely financed by Lloyd George and Lord de Walden.

Rhoscomyl’s estate was £85 and he did not immediately receive an army pension therefore his wife Katherine continued to live in poor circumstances.

She passed away due to heart failure in 1927, aged 45, and is buried in OM’s grave along with their son Rhys.

Curiously, he was buried in Rhyl despite having no apparent connection with the town and the local residents asked who he was, despite the fact that his funeral had a coffin on a gun carriage, draped with the Ddraig Goch, a firing party and 300 troops from the Cheshire Regiment, based at nearby Kinmel Camp.

Legacy

George Owen and others campaigning for greater recognition about Rhoscomyl are hoping to find a new place for the gravestone and cross, which are both in a ‘sorry state’ and say an ideal place for the memorial would be in the grounds of Cardiff Castle.

Owen shared: “The Museum of the Welsh Soldier (housed in the castle) would also be a fitting place. During WWI Owen Rhoscomyl raised the Welsh Horse in Cardiff and Bryn Owen, the late curator of the museum, believed the museum has Rhoscomyl’s WWI era “cleddyf”, or trench sword, in its collections. Just outside the castle walls are the grounds of Sophia Gardens, where Rhoscomyl’s 1909 National Pageant of Wales was held. It was also the location of “Pageant House”, where he and his family lived during the preparations.

“St. Fagan’s Museum of Welsh Life would also be a great place. The museum has Rhoscomyl’s pistol (a muzzle loader gifted to him by Lord Howard de Walden) and his mother’s wedding ring in its collections.”

Owen added: “It is ironic that in Rhyl town cemetery, opposite the church cemetery where Rhoscomyl, 1863-1919, is buried, is the grave of E J Williams,1853-1932, Civil Engineer, who grew up in Mostyn (only a few miles from Tremeirchion where Rhoscomyl lived as a boy).

“E J Williams was the man who went to Patagonia and against considerable odds designed and built the railroad that ran the length of Chubut down to Port Madryn and was an enormous boost to the Welsh Patagonian economy and community living in Chubut.

“He returned to Wales in 1902 and chose to live in the large (now Grade2 listed) Pendyffryn House, Rhyl. There is written evidence held in the National Archive at Aberystwyth that EJW, when in Chubut, was involved at a high political level in the administration of the community.

“It is as yet unconfirmed that Rhoscomyl travelled to Patagonia and was involved in politics there and John S Ellis makes reference to this in his book. It is possible that the two men met but further research is required. Railway in the Desert,Kenneth Skinner, 1984, tells of EJW’s life and work building the railway in Patagonia, no index and out of print, available on ebay.

Rhyl

According to Owen, what is clear is that Rhyl is unaware that two important Welsh historical figures lie forgotten in the town.

HE said: “EJW’s house had a garden of several acres and in the 1930s two streets named Patagonia Avenue and Madryn Avenue were built on land provided by EJ Williams’ family. To my knowledge, as a resident myself in Madryn Avenue, no one in the town is aware of this or to my knowledge has questioned why the streets are so named.”

His grave in Rhyl has two stones: one is a military gravestone, and one is a Celtic plinth which is about to topple over onto the other stone.

This plinth was put there by David Lloyd George eight years after Rhoscomyl’s death in 1927. His wife and son are also interred there. The church cemetery is closed, overgrown and neglected.

Owen added: “Rhoscomyl’s great granddaughter Tamzin Evershed is a solicitor who lives in Helston, Cornwall, and she is in touch with several other members of the family who also support the campaign to rescue his reputation as a forgotten hero.

“He deserves to be brought out of the shadows and remembered along with other Welsh heroes, and where better to start than putting his overlooked and dilapidated memorial right, and in its rightful place.

“The story is of national importance, and I encourage anyone who might be able to help to join our recently launched Facebook group and to give this great man of Wales the lasting legacy he deserves.”

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Owen Rhoscomyl was lucky he died when he did,many people with his mindset and experiences ended up as fascists.

A substantial number of Welshmen joined the International Brigade and fought against the fascists.

Good Lord, my grandfather was a ‘biker’ before getting into a ‘tank’, I hope members of our ‘film industry’ pick up on him…Thanks for the heads-up…

Well said Mab. Please send an email of support to [email protected]. Hwyl George Owen

Owen is such an interesting person to read about! It would be such a shame to see his grave fall to ruin 🙁

Your spot on Seren, OR deserves a better location for his Celtic Cross put in place by former prime minister David Lloyd George.

It would be wonderful to see this grave restored and given the recognition it deserves. Honoring our history and remembering those who made a difference is so important!

Emma. Well said, please send an email of support to [email protected]. Thanks George