Can a song save a language?

Eluned Haf Head of Wales Arts International

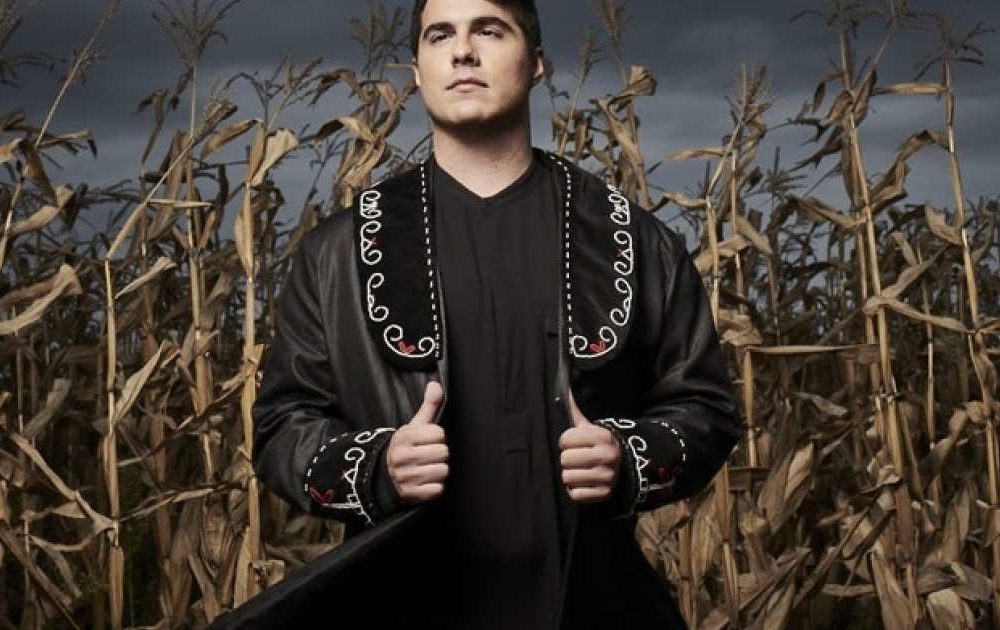

When Jeremy Dutcher performed at Neuadd Ogwen in north Wales during UNESCO’s International Year of Indigenous Languages in 2019, the audience, me included, was mesmerised by his voice and his use of archival recordings from his ancestors, the Wolastoqiyik Nation of northern Turtle Island.

Turtle Island is a name many Indigenous peoples use for North America, including what we now call Canada, drawn from creation stories where the land rests on the back of a giant turtle.

In Canada, the term honours Indigenous nations’ deep connection to the land and acknowledges their histories that predate colonisation.

I could hear and feel that connection in every beat, sound, and breath of Dutcher’s performance that evening, and not at all surprised when he went on to win Canada’s prestigious Polaris Music Prize twice.

If you’ve not discovered him yet, have a listen to his album Wolastoqiyik Lintuwakonawa and tell me you don’t feel this too.

Colonial legacies

During the post-performance Q&A, Dutcher, struck by the Welsh commitment to their language, remarked, “If you can aim for a million speakers of Welsh, I can aim for a thousand speakers of Wolastoqey.” An endangered Algonquian language with only a few fluent speakers remaining,

Wolastoqey is deeply tied to the Wolastoq River and central to the cultural identity of the Wolastoqiyik people.

Like many Indigenous languages facing extinction, it stands as a powerful symbol of Indigenous sovereignty and the enduring efforts to preserve these cultures, languages, and environments in the face of colonial legacies.

This reminded me of ShoShona Kish’s stirring speech when she received the WOMEX 2018 Professional Excellence Award.

She challenged us to truly listen and confront the ongoing injustices faced by Indigenous peoples across the globe.

I hadn’t fully grasped the extent of the horror of the 139 residential schools that existed, where thousands of Indigenous children in Canada and other parts of the Commonwealth were forcibly stripped of their culture and language.

The last of these schools in Canada closed in 1996, shockingly within my lifetime.

But how did I not know this? Why isn’t this common knowledge?

Trauma

These moments had a profound impact on me, opening my eyes to the widespread ignorance and lack of awareness in Wales and the UK about the deep trauma endured by the rich cultures of the First Nations of Turtle Island—what we now call North America.

Colonised by Christopher Columbus and later subjected to the ongoing conquest by millions of settlers, including the Welsh, these communities have faced immense cultural and linguistic destruction, much of which we have overlooked or misunderstood.

What has become clear to me is that, as Welsh people, we often avoid acknowledging our direct and indirect role in colonisation and imperialism, even through the medium of Welsh.

Some try to separate Welsh from Indigenous languages, as if we are somehow exempt from the colonial history we were part of—not just in Patagonia, but also in Canada, the United States, Australia, India, and across the Commonwealth.

This reluctance feels like a form of Welsh “cancel culture,” where failing to admit our wrongdoings allows us to avoid confronting them.

If we don’t recognise our privileged colonial linguistic footprint, we cannot be part of the change we wish to see. While Welsh itself is fragile due to historical oppression—perhaps as the Commonwealth’s first colony—we must also remember that the Welsh were participants in colonisation.

My own family’s history revealed that one ancestor migrated from Penffordd-Las (Staylittle) in Wales to Minnesota, where, in 1862 they were involved in genocide against the Dakota First Nation in America, making our complicity undeniable.

Ancestral journey

In 2022, inspired by Dutcher and Kish’s words and performance, along with my own ancestral journey of understanding, I worked with staff at Wales Arts International to launch the Gwrando / Listening Project as part of the United Nations Decade of Indigenous Languages, inviting Welsh artists to connect with Indigenous languages and cultures from around the world.

With one language disappearing every two weeks globally, and the Welsh language itself at a critical point, falling below 20% of speakers, the project aims to build bridges of understanding, respect, and solidarity.

Through creative collaborations, the initiative hopes to raise awareness of the urgent need to preserve vulnerable languages and inspire efforts to revitalize them.

At its heart, Gwrando also reflects on Wales’ own complex role in colonial histories—while we’ve endured linguistic oppression, we’ve also been part of colonial expansion.

To guide this work, the project has developed a set of principles—always evolving—to help artists form genuine, respectful relationships with Indigenous cultures.

These principles aim to avoid cultural appropriation and foster a shared responsibility for protecting the world’s endangered languages while addressing the global challenges we all face, from cultural loss to climate change.

If you want to see the set of principles currently in development or contribute in a meaningful way to the project, then please get in touch with us at Wales Arts International.

“From silence comes listening”

Artists are particularly good at engaging with social and cultural behaviours, so supporting them through the Gwrando program has allowed us to confront challenging themes and gain valuable insights from their experiences.

When we launched the programme, The Archdruid of The National Eisteddfod, Mererid Hopwood remarked, “From silence comes listening,” a concept that continues to guide us.

By creating space for silence and reflection, each artist involved in Gwrando has deepened their understanding of our collective responsibility, as speakers of small languages, to support other endangered languages and challenge monolingual imperialist thinking—even when it appears in the bilingual context of public life in Wales.

The program also highlights the cultural indifference toward other languages and forces us to recognize that both we and the Welsh language have played a part in global colonisation.

Acknowledging this opens the door to meaningful conversations about our role in collaborating to protect the world’s small and Indigenous languages, both within the Commonwealth and beyond, while providing a platform for Indigenous artists in Wales and across the UK.

Commitment

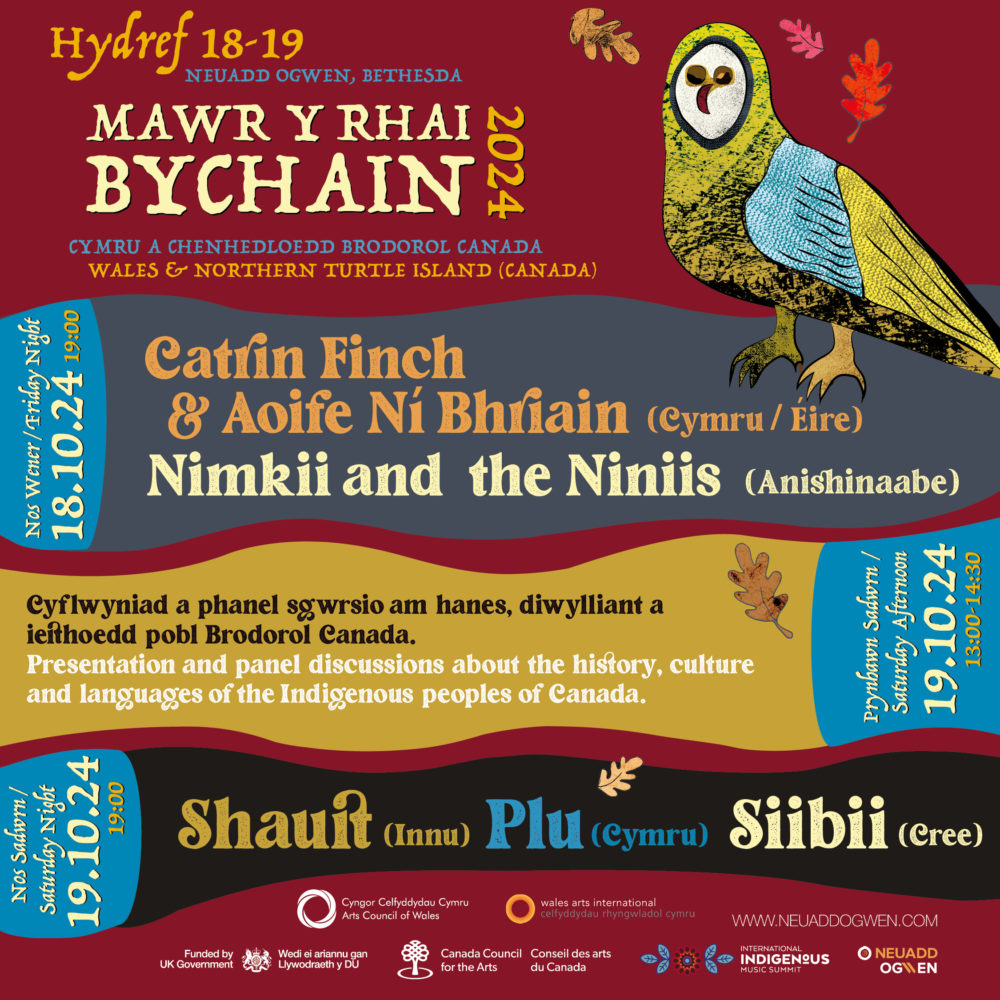

As part of our commitment to the UN Decade of Indigenous Languages, we’re excited to support Gŵyl Mawr y Rhai Bychain, the International Indigenous Languages and Music Festival (October 18-20 in Bethesda).

This year’s focus is on the languages and music of northern Turtle Island (Canada), in partnership with the International Indigenous Music Summit.

The festival will welcome Indigenous Elders, artists, and activists with strong ties to Wales, celebrating Indigenous creativity and wisdom.

Highlights include Cylch Gwrando / The Listening Circle on October 18th in Caernarfon, where we’ll explore global responsibilities to Indigenous languages and discuss fair collaborations, aligned with Wales’ Wellbeing of Future Generations Act.

We look forward to welcoming international guests like JUNO award-winning artist ShoShona Kish (Anishinaabe), curators, and artists including Denise Bolduc (Anishinaabe/French), Shauit (Innu), Nimkii and the Niniis (Anishinaabe), and Siibii (Cree).

Indigenous leaders from British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec, and the Pacific Islands will also join us, creating a space for reflection, learning, and connection before their participation in WOMEX24 in Manchester.

Now is the time for us all to listen, to truly hear the voices of Indigenous peoples and acknowledge the role we’ve played in their stories.

The injustices faced by Indigenous communities across the world are not relics of the past, but pressing realities that continue to resonate today.

As Welsh people, we must recognise our own complex history of both suffering and complicity in colonialism. By facing this truth, we can begin to repair the damage and forge new paths of collaboration and respect.

The Gwrando / Listening project calls on us to take responsibility and it’s a start, but we have so much work to do as citizens of the world who are deeply invested in the preservation of the world’s endangered languages and cultures.

We must act now to protect what remains, to create meaningful connections, and to ensure that these languages and traditions endure.

The future of our shared cultural and linguistic heritage depends on what we do next—so let’s listen, learn, and act together.

Tickets for Gŵyl Mawr y Rhai Bychain are available on Neuadd Ogwen’s website:

Weekend tickets – https://neuaddogwen.com/en/events/mawr-y-rhai-bychain-2024-weekend-tickets/

Friday tickets – https://neuaddogwen.com/en/events/mawr-y-rhai-bychain-2024-friday/

Saturday tickets – https://neuaddogwen.com/en/events/mawr-y-rhai-bychain-2024-saturday/

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Waw, The damage, including extinction, done to languages & culture by imperialism.

But at least Indigenous Elders, artists, and activists can now fly around the world at our expense, to discuss in the global language of English how to celebrate Indigenous creativity and wisdom.

Interesting article, not least because American pop music is responsible for spreading the English language more than anything else. I used to teach EFL and nearly all the students used rock music as a way of learning the language – that and TV obvs

What priviliged colonial linguistic footprint? This Anglo-American nonsense has to stop. Does dim rhaid i ni ymddiheuro. Cymru am byth.