Coalfaces revisited

Tina Carr and Annemarie Schöne’s work Coalfaces is a major feature of the Valleys exhibition currently running at Amgueddfa Cymru in Cardiff.

Their work featured in their award-winning publication Coalfaces in 2014 and now republished by Parthian.

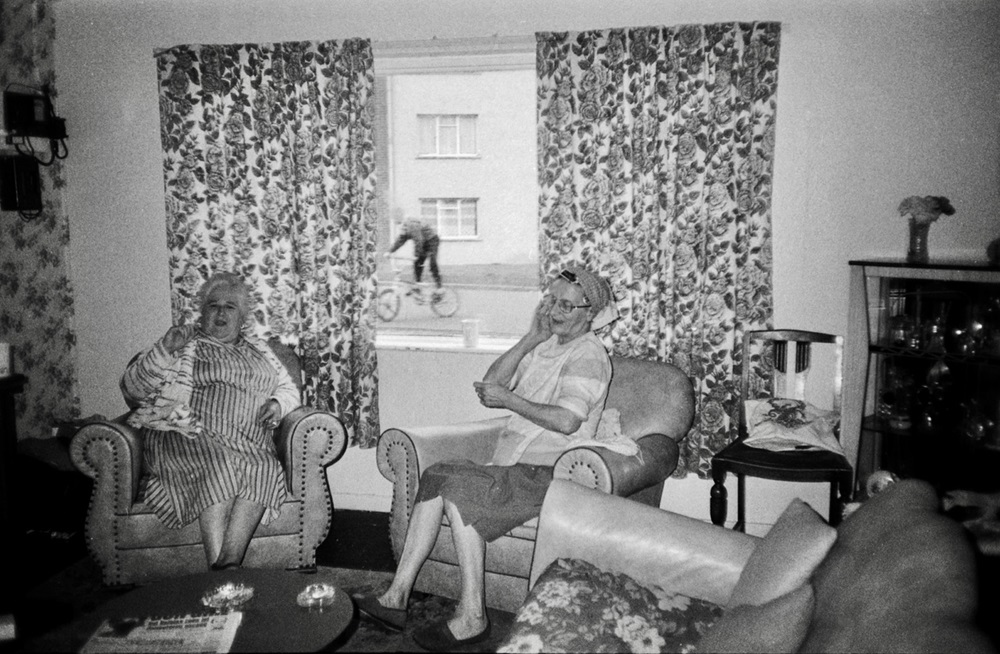

The arresting series of documentary photographs shows the life and landscape of five small settlements in South Wales. These communities in the Afan Valley, after the pit closures, had to deal with high levels of unemployment and found themselves with severe adjustment problems.

Over several years,Tina Carr and Annemarie Schöne worked with the residents of the valley to document the place that they call ‘home’.

The photographs, gritty, beautiful, empathetic, sad and humorous, reflect a hardy and feisty attitude, shared by the residents despite the adversity they are forced to face, and provide us with a much needed reminder of a community all too easily forgotten about.

Their work is introduced and reflected on here by the artist and writer Osi Rhys Osmond

This book comes to us as readers and viewers with a strange duality. It comes to challenge and it comes to praise. It comes to challenge those that have power over other people’s lives, and to passionately accuse those who dispense that power in such a cavalier fashion.

It is, in that sense, an indictment. And it comes, primarily perhaps, to praise those, the subjects of these photographs, who by their persistence, optimism and social energy have constructed a meaningful culture out of tragic and traumatic circumstances.

Acclamation

And it is, in that sense, an acclamation. Additionally these images, words and recordings exist to confront those deeply embedded stereotypes of rep-resentation that the mining community have traditionally suffered, and to offer documentation as an act of social witness that records and gives voice to a people who usually remain unheard.

I cannot look at these photographs, the text or the accompanying DVD, without feeling an enormous sense of anger and shame. These people are my people and this community is similar to the community from which I come, and in which many of my family still live.

What has happened to these people? What has happened to this place? Why have they, their community and communities like theirs across South Wales been abandoned to face the ravages of post-industrialisation with less consideration for their needs than that given to the natural world that surrounds them?

The answer seems to be that the physical environment of the South Wales Valleys is now a commodity that can be traded in the tourist markets of the world. The people and mining culture that created this landscape cannot be commodified, other than as caricatures or museum attendants, so sadly they are no longer necessary.

They have become a people stranded by history as the great wealth of the coalfield bypassed the communities that produced it leaving them with deep social and physical scars, powerful collective memories and an extraordinary and very necessary social resilience in the face of the constructive in-difference of the political elites.

The coalfields of Britain, particularly the mining valleys of South Wales, have been a site of struggle and contention since the rapid acceleration of deep mining at the beginning of the 19th century.

The establishment powers quickly saw those communities as a potent threat to political and social order as hordes of migrant workers from Wales and beyond poured in to create a novel and unfamiliar society.

From their beginnings and especially during the mid 19th century struggle for social justice and political rights they were seen as dangerous, a breeding ground for radicalism and dissent, promoting fears that the mining masses were developing into a savage beast that might well prove impossible to control.

With the demise of deep mining and the ensuing endemic unemployment, the policy of treating the economically bereft as problematic and socially contagious continues and is clearly evident in the isolation of these communities, not just naturally by geography, but politically as the governing hegemony ignores their dire circumstances, while taking their political allegiance for granted.

One of the chief problems of depicting the mining and post mining communities is that both the people and the places have made and continue to make very compelling images.

The compositional dynamic of the familiar pit-head winding gear and the characteristic faces of the people, miners or their families, have offered a very potent subject matter for artists, photographers and film makers.

Now, the aesthetic certainties of the past are being overtaken and undermined by new ways of seeing and the post- industrial world needs a new grammar of representation.

The traditional pictorial representation of mining communities is well understood in both painting and photography. Depictions have often been loaded with a peculiar and constantly changing mix of fear, sentimentality and cautious romanticism.

The newspapers of the early 19th century saw the novel mining settlements as newsworthy, a convenient source of images that engendered social unease among the new middle class city dweller. They were good for sales though, as the press barons of Victorian Britain placed our mining communities in the same category as contemporary ‘redtops’ put the illegal immigrant or asylum seeker of today: as the unpredictable and dangerous other.

And interestingly, although their political radicalism threatened bourgeois society, mining disasters made compelling stories, having all the necessary narrative ingredients of waiting and tension, suffering, loss and episodic unfolding that made the next edition eagerly anticipated, a melodramatic approach that remains the standard media response.

The limitations of Victorian printing processes meant that newspaper images were published in black and white, by means of engravings made from drawings initially and later from photographs.

The medium of engraving profoundly influenced the construction of a formal language of representation for the mining communities, soon reinforced and confirmed by the arrival of photography.

The early cameras affected ensuing depictions, as the slow shutter was unable to express action, which continued to be the province of the engraving, and subjects had to be carefully posed, with the result that they tended to portray the miner and even the community as a type, clearly seen in the work of William Clayton in the mid 1800s.

This view persisted into the 20th century and developed into an anthropological representation of the mining classes as an exotic other to be pictured in a grittily romantic manner. A later exception to this, at the beginning of the 20th century, was W. E. Jones, who, coming from that community, made much more celebratory photographs of the mining world than those which preceded him and many that were to follow. By the depressions of the twenties and thirties photographs of mining communities, especially those of South Wales, naturally reflected the much gloomier public mood.

Bill Brandt and Edith Tudor Hart, who visited South Wales in the 1930s, heralded in some respects the later photographic work of the American, Walker Evans, who, while commissioned under the Rural Resettlement Administration, created a powerful aesthetic of economic deprivation that rapidly became the norm for representations of depression period social degradation. Edith Tudor Hart’s work demonstrates great human sympathy, gracefully depicting children and the domestic among the industrial, and while much of Brandt’s work showing the miners in their workplace focused strongly on abstract values, his images of the miner at home, eating, resting or washing, often with the aid of his wife, are gentle and compassionate.

The very nature of the coal industry, with its ubiquitous black spoil, created an atmosphere that easily lent itself to the grainy exigencies of the black and white photography of the time. Carefully composed representations of this dusty world seemed naturally ordained to appear in a darkly carboniferous pictorial conspiracy as a form of visual political confirmation.

It can be argued that for much of the mid 20th century these ‘types’ were almost always shown as the heroic scapegoat, the convenient sacrificial victim, who would suffer with dignity, for all our sins on the altar of capitalist excess and exploitation. Although it is possible to suggest that the mining community was itself compliant in the construction of certain ongoing stereotypes, some practitioners, chiefly photo-journalists, encouraged suitably melodramatic poses and it is evident that as soon as a formal language of representation had come into being, the subjects themselves quickly learned what was expected of them as they faced the camera.

And so they did, in the work of a wide range of practitioners: from Brandt and Tudor Hart and later Eugene Smith in the forties and Robert Frank in the fifties.

Films including Proud Valley, The Citadel, and How Green Was My Valley consolidated and perpetuated a formal aesthetic of romantic representation for colliery and community life. The language of representation was consolidated and confirmed by the work of artists, many of who were from the mining community, some, like Vincent Evans and Archie Rhys Griffiths, even having been colliery workers themselves.

These examinations of working class society were continued more critically in the documentary film movement that began in the thirties and from which the Mass Observation project developed: begun by Humphrey Jennings and others in the 1930s and focusing strongly on the mining industry. Jennings himself went on to make Silent Village during the Second World War, a film in which the Welsh mining village of Cwmgiedd stood in for a defiant Czech community ravaged by savage revenge during Nazi German occupation.

Jill Craigie’s 1949 film Blue Scar carried on the tradition of mining documentaries, this time celebrating the recent nationalisation of the industry that became the National Coal Board and rapidly established its own documentary film unit.

As well as documentaries, feature films such as The Citadel and How Green Was My Valley demonstrated an admiration of and sympathy for the mining community. These films reflected appreciation of the strong and timely anti-fascist sentiments and brotherly solidarity that underwrote the inter-national socialism of the miner’s major political ideologies; for many, they and their communities were a living embodiment of the socialist dream.

In 1966 the Aberfan disaster saw many pitiful images in the press and television of a mining community in trauma. Later the American photographer I. C. Rapoport spent time living with the bereaved community and photographed the slow process of a society regaining its collective composure in a series of touching, dramatic and melancholy black and white images. By now the end of the South Wales coal industry was in sight and the remaining mining communities were haunted by the threat of closure and redundancy.

Shortly after Aberfan, and deeply affected, Karl Francis, himself from a mining family, began his career as a film maker, writing and directing a number of moving, naturalistic, drama-documentary films, including Above Us the Earth that extolled the resistance and radicalism of mining communities under threat of colliery closure.

Since then, David Hurn and Philip Jones Griffiths and Ffotogallery’s Valley Project have photographed the collapse, death throes and post mortem of a declining industry and its damaged society in black and white images that discreetly confirmed, smiled at and demolished some of the longstanding representational clichés.

Roger Tiley, a photographer from the mining community, photographs the post mining valleys using a traditional documentary approach to working class life, extending his interest into an international concern for heavy industry and its workers. Recently, younger photographers like Paul Cabutts have looked in a completely new way at the mining valleys, giving an ironic post-modern twist to long-standing pictorial expectations.

Overall, the mining community is probably the most photographed industrial subject of photographic history.

This powerful and perceptive publication, coming as it does some time after the demise of deep mining in the upper Afan Valley, shows the community and landscape twenty or more years after the closure of the local collieries.

The photographs and filmed interviews were made more than fifteen years ago, but very little has changed since then. The people and their enclosing valley are sympathetically depicted as stranded in a geographic cul-de-sac where industrial history itself has come to a dead end.

Today in these communities it seems as though history has passed by, they are in a strange sense stranded, standing outside history.

Although the last mine in the upper Afan Valley had closed as early as 1969, large numbers of local men continued to travel to the mines of the adjacent valleys and this remained a mining community long after the local mines had gone. Following the sudden tragedy of initial closure, the gradual death of adjacent collieries and associated job losses initiated a slow haemorrhage of optimism. The rhythm of such events, unrelenting and unavoidable, can shock a community in the manner of a gradually unfolding natural disaster.

The trauma, though not immediately perceptible, is, however, as profound as that triggered by a major earthquake or tornado.

To visit the upper Afan Valley now is to enter a time warp, a place where two unconnected histories seem to be unfolding. Two different realities confront the visitor, on the one hand the very evident reality of unrelenting post-industrial change and neglect, and on the other the brave new official optimism of rebranding, where the leaflet reigns supreme, shiny and hyperbolic, promising a rebirth for this community and a fabulous future for the valley as the hub of a carefully planned tourist industry that will create the employment opportunities of future generations.

As we have seen, in the wake of post-industrial decline each individual feels redundant, and eventually so does the whole community. In these isolated valleys the promise of new work has yet to materialise to any meaningful extent.

To make the area attractive to visitors, large amounts of public funding have been committed to remedial landscape work, efforts that have been largely cosmetic, acting as a kind of post-industrial botox.

The smile has disappeared from the landscape and is replaced by the rictus grin of the unnaturally realigned.

The Glyncorrwg Ponds project, welcomed and eagerly accepted as almost a local idea at its inception, has become to some bitter evidence of the failure of such schemes, although it functions perfectly well as a fishing facility. Among the filmed interviews the disappointed expectant workforce of unemployed local men air their views and they do so in a very trenchant manner.

The many visitors to the extremely popular cycle trails come for an adventure that utilises the wild landscape in a promiscuously short-term relationship with the geography that bypasses the social reality of life after coal for the local population. That outsiders enjoy their breathless leisure time in full view of a society in decline makes a harrowing accompaniment to the deeply felt hopelessness of the long-term unemployed.

The interviews encompass every generation, from veteran colliery workers and former railway employees to young men, young mothers and their children. Their words reveal the reality of life ‘after coal’ for many of those left behind in the aftermath of industrial decline.

Nevertheless, considering the fate that has befallen their community the people of the Upper Afan Valley remain friendly and unexpectedly optimistic. The pubs and shops, although many fewer than in the old days, are still very welcoming, as are the homes, for the people are as hospitable as they have always been.

The betting office was among the warmest and most inviting places in Croeserw. Carpeted and snug and with a regular clientele discussing form while large wall-to-wall television monitors were simultaneously showing all the events on which it is possible to place a bet, mostly horse races, beamed by satellite from one glitteringly successful social milieu into a very different reality.

The physical wellbeing of the horses, never mind their owners, their energetic beauty, shiny flanks and highly toned limbs contrast strangely with the pallor of many of the gamblers.

Looking at the images in this series I am constantly reminded of the time I spent in Palestine. There, another community with even greater social, political and employment problems, and the sense of powerlessness that they engender, constantly awaits unfolding events with trepidation.

The people in these photographs stare out at the lens and appear in one sense to outstare it. There is the feeling of transience, languor, of time moving slowly, of discontinuity or hiatus as a condition of life. Expectant waiting is the sole continuance; people are out in the world, watchful, looking at a world passing them by.

Those photographed are an inseparable part of the landscape, and in the strange way that the topography of the valleys tilts our visual per-spective, their presence against the rising background, whether inside their homes and social spaces or out in the landscape, emphasises their deep attachment to the very earth, houses and architecture of their villages and environs.

Strangely, the recent past, when re-examined through the photograph, can sometimes look more remote than the distant past. The earlier black and white images spoke effectively to previous times, although these post-coal pictures, having shed the dull sheen of the black dust, confirm the final eclipse of coal, now merely a memory.

The ubiquitous dust darkly flavoured the whole atmosphere of the mining world; now the new clarity in the air is best served by images in colour. This is a physical phenomenon rather than a social one, and some might observe that the bright photographic hues reflect the fact that we live in more chemically enhanced times and that this more accurately mirrors the harsh social realities of the present. The conflict between the beauty in the image making and the hardships of those depicted creates a pictorial tension, a visual dilemma as photography as a political act and photography as interrogation becomes hostage to photography as an artistic quest.

That, in this case, is done knowingly, for in their engagement with the people the photographers have successfully resolved questions of responsibility and complicity, power and exploitation to the satisfaction of both parties.

For although made so many years ago, these thoughtful, beautiful and powerfully constructed, coloured images convey a fascinating pictorial intrigue and a very contemporary vitality that is a reflection of the willing and enthusiastic co-operation of all the participants. And it is this that makes this work so distinctive; from its inception, the artists, Tina Carr and Annemarie Schöne have been committed to a collaborative project that immediately and properly involved the community in its creative philosophy.

The people depicted are not simply the subject of the photographs, they inhabit them and contribute to them, are a very real part of them and of the process of bringing them into being. Therefore, these revealing photographs are not condescending in the way that many of the earlier ones were, largely because the characters depicted are able to positively influence the terms of their own representation.

Many of the earlier images told us only about the superficial appearance of the subjects and from this we can have very little idea of the actuality of the lives depicted, as they are usually seen not as lives but as ciphers for a particular social or political viewpoint, used to illustrate something other than the reality of the subjects’ own experience. In these photographs we are closer to seeing people as they see themselves and that is the essential difference between these tenderly revealing photographs and the earlier and more deliberately aesthetically bleak documentary images.

Throughout the exercise the artists have been at pains to highlight the positive attributes of the community, the keen gardeners, the mechanics, home-makers, people with social skills, hobbies and many other attributes that are often overlooked by officialdom.

There was the hope that this project could become a kind of audit, a way of enabling the community to realise hope beyond their present difficulties. The newer interventions, like the Communities First scheme, have taken these ideas as their starting point, but critically, until people feel a sense of ownership their beneficial engagement will never be fully realised.

The dramatic appearance of the physical landscapes as one approaches the valleys of South Wales has softened since the demise of deep mining. Then the feeling of entering another world was palpable and the strange otherness of this place naturally drew seekers after an objectification of certain aesthetic and societal values.

Those conditions, social, topographical, natural and man-made, combined with the newly arrived and diverse workforce and its dependents, resulted in a community and landscape of compelling com-plexity. This remains a vigourous community of extraordinary resilience; a community initially bonded together by the tribulations of harsh but interdependent mining life, although now perhaps distinguished to some degree by the injustice of abandonment.

These greener gentler valleys of contemporary South Wales still carry the scars of their settlement and exploitation; a process that for the most part took place over a very short period. The historical evidence of this is clear in the landscape and in the way that events left their mark not just on the inhabitants, but on the hills, the settlements and the valley bottoms.

These photographs, words and filmed interviews are important for that reason; for they hold within themselves the story of a people and a place, they have become social, physical and human archaeology.

They are a record and a memorial to a changing world. They can be read and interpreted to reveal the historic story of a mining valley through the relatively short period of its birth, growth and decline as an industrial community. The intensity and rapid acceleration of change that this involved and the abrupt and traumatic catastrophe of its sudden collapse are all held within the encompassing grasp of these powerful words and images.

The mines are gone, but under and above the ground this community has embedded itself in the very earth and rock into which it once tunnelled and mined, and so the people persist, they survive, they blossom and live with a defiant, cheerful natural exuberance, they construct their domestic and social stages, physically and metaphorically, they walk, they talk, box, love, marry, give birth and mourn, they play, learn, celebrate and dress up, commute, worship and garden and are photographed and so are now honoured, remembered and held fixed in time in this extraordinarily beautiful act of accusatory and celebratory documentation.

Osi Rhys Osmond was an artist, writer, teacher, performer and broadcaster from a Sirhowy Valley mining family. He contributed regularly to print magazines, including Planet, and was published extensively on the arts and culture in both Welsh and English. He had a longstanding and critically vigilant interest in depictions of the mining community. He died in 2015. His work can be seen at Oriel Osi in Llansteffan curated by his wife, the musician Hilary Rhys Osmond.

Tina Carr & Annemarie Schöne lived in Ceredigion, Wales for over three decades. Their work has won many awards and is held in public and private collections both in the UK and internationally. The Coalfaces project received the John Morgan Writing Award in 1995. In 2003 Tina Carr & Annemarie Schöne were awarded the prestigious Creative Wales Award and in 2007 a production grant from the Arts Council of Wales for new work with Roma communities in Europe.

Coalfaces is published by Parthian and is available at the Amgueddfa Museum and for pre-order.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.