Cofiwch Dryweryn: A nation remembers Tryweryn

Stephen Price

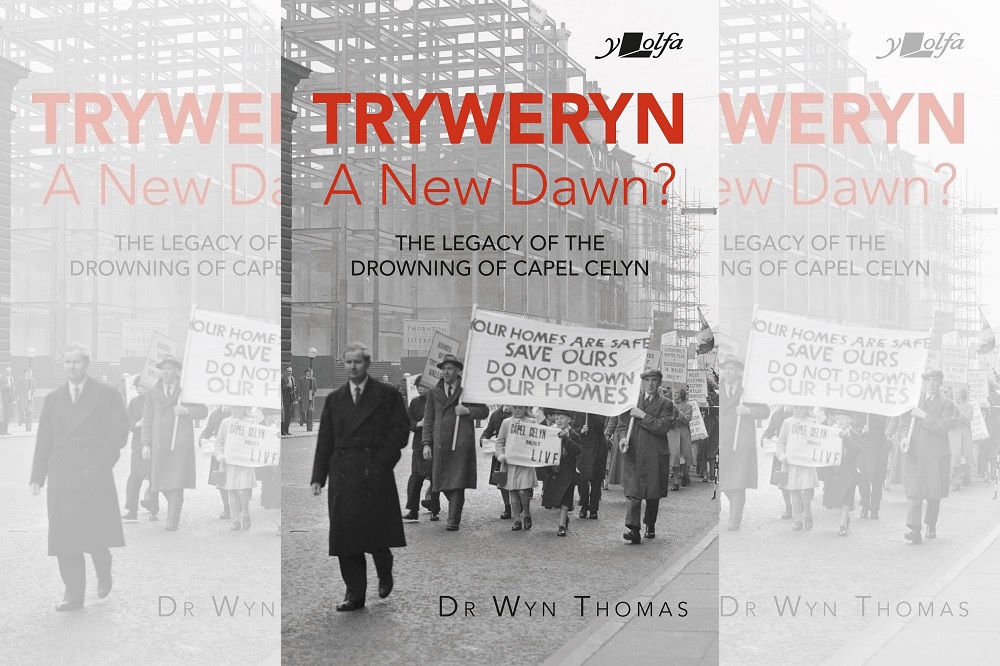

Today, Wales remembers the Welsh speaking village of Capel Celyn, which was drowned to create a reservoir to supply Liverpool and Wirral with water on 21 October 1965.

The Tryweryn flooding was opposed by 125 local authorities and 27 of 36 Welsh MPs voted against the second reading of the bill with none voting for it.

At the time, Wales had no Welsh office (introduced in 1964) or any devolution, yet its act sowed the seeds for the status of Wales’ language and politics ever since.

The villagers first knew about the proposal a few days before Christmas 1955, from reading about it in the Welsh edition of the Liverpool Daily Post.

The villagers created the Capel Celyn Defence Committee, which debated and denounced the scheme all over Wales through newspapers, radio and television.

The villagers marched twice to Liverpool in 1956 to make their objections known. However, Liverpool councillors voted overwhelmingly to proceed.

In 1957, a private bill sponsored by Liverpool City Council was brought before Parliament to develop a water reservoir in the Tryweryn Valley. The development would include the flooding of Capel Celyn.

By obtaining authority via an Act of Parliament, Liverpool City Council would not require planning consent from the relevant Welsh local authorities and would also avoid a planning inquiry at Welsh level at which arguments against the proposal could be expressed.

This, together with the fact that the village was one of the last Welsh-only speaking communities in the area, ensured that the proposals became deeply controversial

On 19 October 2005, Liverpool City Council issued a formal apology for the flooding. Some in the town of Bala welcomed the move, though others said the apology was a “useless political gesture” and came far too late.

Mural

The iconic and much-copied Cofiwch Dryweryn mural was created by the writer and academic Meic Stephens, the father of Radio 1 DJ Huw Stephens.

Though he made an enormous contribution to Welsh literature he said that nothing had as profound an impact on the popular imagination as the Cofiwch Dryweryn mural.

The white letters on the blood-red background, the red of the dragon, the red of Wales, symbolise an act of defiance; a readiness to stand up and be counted.

One of Wales’ greatest symbolisms of our pride, our sense of defiance, and our determination to protect our language.

Battle cry

Writing for Nation.Cymru, Gareth Ceidiog Hughes said: “But that was not the end of the story. It was the beginning of a fightback. The visceral realisation of powerlessness created a determination to take back the power to defend our communities and the culture they incubate and engender.

“It sparked a determination in Welsh speakers, especially, to fight for linguistic rights. Many of those rights have been won. Welsh speakers now have the right to access public services in the language.

He added: “We now have S4C and BBC Radio Cymru. Welsh medium education is being expanded.

“It also reignited the battle for Welsh autonomy. We now have our own Senedd. These things matter.

“Cofiwch Dryweryn (Remember Tryweryn) is a battle cry. That battle cry was heard and acted upon. An army of activists charged the lines of discrimination, bigotry, and arrogant dismissal damaging the language. The mural captured the zeitgeist. It captured the mood of a nation.”

Animation

An animated film telling the story of Tryweryn debuted at Cardiff International Film Festival in October 2021.

The film by Osian Roberts, who comes from Llanerchymedd on Anglesey, was selected to form part of the ‘Welsh Films’ category at the festival.

Osian Roberts studied an Art Foundation course at Coleg Menai, Bangor, before going on to study BA Animation at Manchester Metropolitan University.

He said that he viewed the film festival as an “opportunity to get the story out” of the drowning of Capel Celyn to a wider audience.

“I worked really hard on the film during the pandemic, and I was able to put in the hours because I was spending a lot of time in the house,” Osian Roberts told Golwg360.

“I worked on the film, the animation and so forth, on my own – and then I had someone to help me with the music.

“I’m just really proud that the film was chosen, it’s a little surreal really.”

But when he discussed the film with his friends and fellow students at Manchester he realised that the history wasn’t as well known as he thought.

“Over the border in England, I noticed when I was pitching the idea at university that not many people had heard the story,” he said.

“They knew the wall, but not the story.”

The event has continued to influence Welsh art and literature ever since, and has inspired songs such as the Manic Street Preachers’ song Ready for Drowning, Enya’s song Dan y Dŵr (“Under the Water”) from her self-titled album of 1987 and Tryweryn by renowned harpist Catrin Finch.

Reservoirs by R. S. Thomas appeared in Not That He Brought Flowers, published in 1968. It was written soon after the opening of Llyn Celyn and Llyn Clywedog.

Reservoirs

There are places in Wales I don’t go:

Reservoirs that are the subconscious

Of a people, troubled far down

With gravestones, chapels, villages even;

The serenity of their expression

Revolts me, it is a pose

For strangers, a watercolour’s appeal

To the mass, instead of the poem’s

Harsher conditions. There are the hills,

Too; gardens gone under the scum

Of the forests; and the smashed faces

Of the farms with the stone trickle

Of their tears down the hills’ side.

Where can I go, then, from the smell

Of decay, from the putrefying of a dead

Nation? I have walked the shore

For an hour and seen the English

Scavenging among the remains

Of our culture, covering the sand

Like the tide and, with the roughness

Of the tide, elbowing our language

Into the grave that we have dug for it.

by R. S. Thomas – from Not That He Brought Flowers (1968)

View this post on Instagram

In a poignant Instagram post shared today, Plaid Cymru wrote: “75 people lost their homes in Tryweryn, and 12 farms, a school, chapel, and post office disappeared under the water.

“Capel Celyn wasn’t just a village. It was one of the last communities to speak only Welsh. Its loss came to symbolise more than just the pressures on our language—it proved how powerless Wales was in the face of Westminster.

“Today, we’re lucky to have more of a voice, with 4 Plaid Cymru MPs in Westminster and our own Senedd. But Plaid Cymru is still fighting for the powers Wales deserves and a future where our communities are never overlooked again.”

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Y mae pob pentref yn Dryweryn bellach, diolch i gynlluniau gwladychu lleol Llywodraeth Cymru. Y mae’r gelyn yn y gaer. Y mae’r pydredd oddi fewn.

Liverpool may have apologised for it’s actions but the establishment in England still treats Cymru with far far too much disrespect, irrelevance and contempt. It’ll never change, not until we get our independence and international respect as a sovereign country in our own right. Even then, if England doesn’t come to terms with that – who gives a toss.

The Labour Government in Westminster is eyeing up some of our valleys. Expect announcements in the months ahead regarding water. Miliband wants more dams.

How can people read about stories like this, and many other things that have gone in the 60 years since, where the Welsh people have no say over their own future and not want independence? Cymru am byth

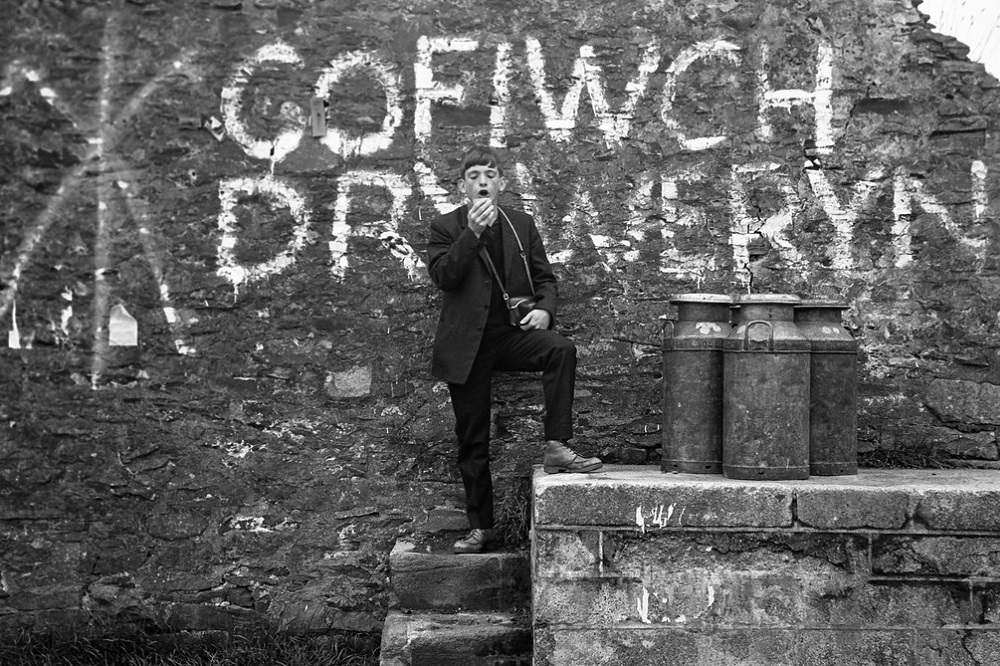

The old photos illustrating this story recall for me the first time I saw the ‘COFIWCH DRYWERYN’ graffito at Llanrhystud, back in my student days around 1966 when the bus on which i was travelling passed it by. If memory serves, it was then just white letters on the old stonework, and ‘Tryweryn’ was unmutated. It probably says a lot about how relatively little heed events in Wales received east of Clawdd Offa back in those days that I – an English lad brought up barely thirty miles from the Welsh border – had no idea at all where Tryweryn… Read more »