From Chartist rebel in Wales to mine owner in Australia: the amazing story of Zephania Williams

Martin Shipton

Chartist rebels from Wales were treated more harshly than their counterparts from Ireland, according to a book that examines what happened after they were transported to Australia.

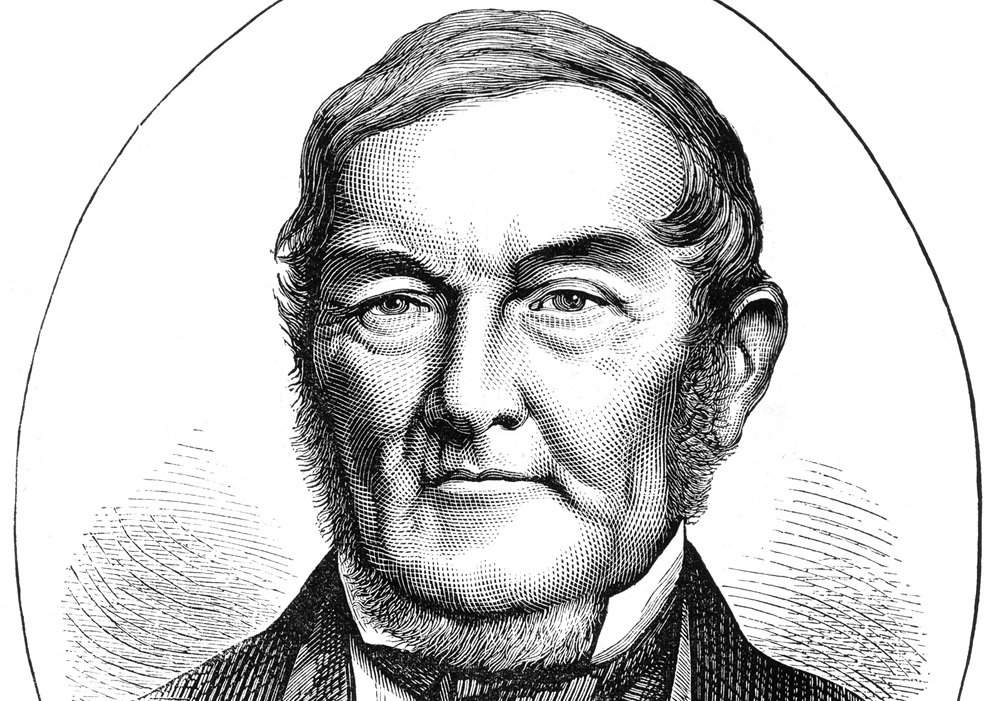

Zeph the Rebel, by the academic David Martin Jones, looks particularly at the case of Zephania Williams, a coal miner and publican from Argoed in the Sirhowy Valley who was one of the leaders of the ill-fated Chartist Uprising in Newport in 1839.

At a time when only a small proportion of the male population was allowed to vote, the Chartists called for votes for all men aged 21 and over, the secret ballot, no property qualification for MPs, payment for MPs, equal constituencies and annual parliamentary elections.

Miners

Around 4,000 Chartist sympathisers marched on Newport, including many miners from nearby towns and villagers. Some were arrested and detained in the town’s Westgate Hotel, where crowds of their comrades gathered, hoping to free them. Fighting broke out and soldiers were ordered to open fire on the protesters, killing up to 24. Four soldiers as well as the Mayor of Newport were injured.

The rebellion was crushed and the leaders convicted of treason and sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered. The sentences were later commuted to transportation.

Williams was taken to Van Diemen’s Land, later renamed Tasmania, where by 1843 he was employed in casting pipes to bring water to the penal station at Impression Bay on the Tasman Peninsula.

It was suggested by Williams’ fellow convict William Jones, who had gained favour with the authorities by acting as an informer, that Williams should be employed as an overseer at the Jerusalem mine in Coalbrookvale. But despite a shortage of skilled labour, the authorities rejected this proposal.

Instead he was employed as a constable in Hobart, the main town on the island, at a salary of 12 shillings a week.

‘Mortifying’

Williams wrote in a letter home to Wales that he considered the “faction” who decided he should do this job had deliberately chosen this situation, “believing … it would be mortifying to my feelings to be made a tool or instrument of persecution. However, they soon found out their mistake, that I was more ready to sympathise than oppress.”

The book states: “As a result of his incompetent policing, in February 1844 he was ‘removed’ to New Norfolk Hospital assuming the role of watch house keeper. Reported for misconduct when found locked in the watch tower with a female prisoner in August 1845, he was subsequently ordered not to be employed as a watch house keeper. Shortly after this reproof, the ‘lunatic’ inmates of New Norfolk rioted. Rather than let the military forcibly restrain the inmates from setting fire to the asylum, Williams offered to pacify them. This he did successfully.

“So impressed was the new governor Sir J Eardley Wilmott, that he sent a memorial to the Colonial Office in London recommending Williams along with 12 other prisoners for a ticket-of-leave. Significantly Williams was the only applicant declined by the Colonial Office. Gladstone, at the time Secretary of State responsible for the Colonies, was instrumental in maintaining an uncompromising attitude towards the Welsh rebels.”

Indentured

In 1846 Williams was indentured as a servant at a Launceston hotel, where he again encountered William Jones, whom he described as “a character so repugnant and odious to my feelings [that] I forbade him ever to speak to me again”.

The quarrel resulted in Jones informing on Williams as he embarked on a plan to abscond to New Zealand with another former Chartist firebrand, William Ellis. Williams was sentenced to hard labour in some mines.

His fortunes looked up after he was released from hard labour in 1848. Following an interlude when he was indentured as a servant to four businessmen interested in mining, he received his ticket-of-leave in 1849, meaning he was now a free man. Now in his fifties, he embarked upon a largely successful career as a coal prospector, mine owner and manager.

He brought over from Wales his wife Joan and children Llewellyn and Rhoda, employing his son to find Welsh migrants to work in his mines and plough the land he had bought in conjunction with a Hobart syndicate.

The book states: “By 1862 Williams had not only opened and closed a colliery at Denison, he had also opened mines at Nook and on the Don and built 40 brick cottages to accommodate the Welsh colliers recruited by his son, and who had migrated in 1857.

“As early as 1853, the residents of Port Frederick, on the Mersey, had presented Williams with a silver cup ‘for perseverance in opening the coalfields in that vicinity’.

“In fact, by 1862 the Launceston Advertiser described Williams as ‘the discoverer of coal in Tasmania’ rather than as a Chartist. In other words, Williams’ identity altered in the course of his exile from radical Chartist to coal prospector, pioneer and entrepreneur.”

Publican

After 1862 Williams returned to his former trade as a publican, together with his wife Joan running the Don at Davenport against significant local opposition. He died in 1874, in his 80th year.

In his preface to the book, Dr Tim Williams, the series editor, writes: “The Zeph of Dr Lones’ account reminds us that the Britain from which the great Chartist was expelled to this ancient but fast-growing and changing Great South Land was itself no monolith, exhausted at the end of empire. It was an economically dynamic force exploding into global dominance that yet was a unique multi-national polity, riven internally by fierce ideological contestation, cultural differences and conflicting identities and values.”

Dr Williams goes on to state that Williams’ Welsh culture and identity led to his being treated more harshly than Irish rebels, who seemingly benefitted from the political influence in the US of a fast-growing Irish migrant population.

He concludes: “Williams’ travails and then successes in Australia inevitably raise the fascinating counter-factual question of how such individuals would have fared in Britain had they not been transported, but also the real world implication of what his ultimately successful trajectory after he left Port Arthur may say about the nature of the country to which he had involuntarily come but in which he afterwards willingly stayed.”

Zeph the Rebel by David Martin Jones is published by Publicani at £12.50.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Any idea where this book can be purchased? Does not seem to be available in the UK!

The Irish diaspora in the USA was a significant factor in the success of the independence movement. De Valera, who expressed his condolences for the death of Hitler, was American born.

Another life: Sir Alfred Lewis Jones K.C.M.G.