Gwyneth Vaughan, lost folk traditions and a place for women in the Welsh canon

Adam Pearce, Editor Llyfrau Melin Bapur Books

Literary canons are powerful things. A collective understanding that certain writers and texts represent the core of a tradition is essential if we are to understand that tradition as a thing in and of itself.

We cannot talk about English Literature, for example, without the shared understanding that when we do so we’re talking about a canon of individuals—Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Austen, and the rest.

A canon turns a set of books into a literature. This is the first powerful thing about a literary canon.

The second powerful thing about a literary canon is its power to exclude: writers who are pushed to the margins because of their class, their race, gender, or simply because what they wrote about wasn’t to the taste of publishers, academics, or audiences.

Importance

When it comes to minority cultures, like Welsh, the function of a canon is doubly important.

Newcomers to our culture need to be able to be directed to those works and writers who we feel represent the best of us; yet in a media landscape dominated by English our opportunity to learn about our own literature is too often limited.

This means that those efforts we do make to form, define and promote our canon are absolutely crucial.

But for a minority language, the power of the canon to exclude is also amplified.

With fewer writers, a small audience and a small academic base whether a writer is lauded or forgotten can hinge on the efforts of a tiny group of individuals, without which writers are doomed to languish in obscurity.

One such writer who has never enjoyed canonical status in Wales, yet who surely deserves at the very least a re-assessment, is Gwyneth Vaughan, the pen name of Ann Harriet Hughes (nee Jones).

Born in Meirionnydd in 1852, she took up writing comparatively late in life when the death of her alcoholic husband forced her to find a way to maintain her family.

After an inauspicious start as an Agony Aunt, her mature period as a writer was quite short, beginning at the turn of the twentieth century and lasting until her untimely death in 1910; however during this period she was enormously productive, writing the three very substantial novels which represent her literary legacy (a fourth was mid-serial when she died).

Vaughan’s novels—written in a period the Welsh novel was still young and subject to restrictive expectations—are enormously ambitious works.

The first, O Gorlannau’r Defaid (From the Sheepfolds), completed in 1903, is set during the Religious revival of 1859, but her second novel, Plant y Gorthrwm (Oppression’s Children), completed in 1905, represents perhaps a fuller flowering of her art.

Taking as its setting the infamous Election of 1868, the novel follows the fate of tenant farmers and their families evicted by their landlords (or, in this case, the stewards managing their estates) for voting for the Liberal party (in an age where voting was still public).

This is a subject for a novel which, I suspect, will hold immediate appeal for many Welsh readers today; and though as a work of fiction the novel is primarily concerned with its characters rather history, it has immense significance as a part of the artistic response to a significant event in our national story.

Feminism

Perhaps of greater appeal still is the novel’s status as a proto-feminist text. Although barred, because of their gender, from the democratic act around which the novel’s plot revolves, the novel’s main characters are mostly female: the self-sacrificing daughter Rhiannon, the precocious bookworm Dyddgu, and the neurodivergent Elin, whose perceived eccentricities allow her to carry out a number of acts of resistance undetected.

When one considers the extremely limited roles given to women in Welsh novels, even great ones, prior to Vaughan’s time—being mostly limited to romantic interests, maternal roles or domestic comic relief in male-centric stories—Vaughan’s role in insisting on genuine agency for her female characters is nothing short of revolutionary.

As Rhiannon asks aloud in the novel when asked why women should receive an education, “Onid gwaith anodd iawn yw i fachgen barchu ei fam pan nad yw mewn uwch sefyllfa na chader neu fwrdd yn y tŷ, neu, os mynnwch, un o’r anifeiliaid oddi allan?” (Is it not difficult for a boy to respect his mother when her status in the house is no greater than that of a chair or table, or, if you like, one of the animals outside?).

Her third novel, Cysgodau y Blynyddoedd Gynt, (The Shadows of years gone by) is perhaps her most satisfying novel from a literary perspective, yet amazingly has never been published as a book following its initial serialisation.

Set in the early part of the nineteenth century in a fictionalised version of Aberdaron, it is a complex, and once again, an ambitious work.

Its main plot revolves around the local Member of Parliament, a rather nefarious character and serial womanizer, and his attempts to ensnare a young Scotsman of noble birth to marry his illegitimate daughter.

Villainous landlords are ten a penny in Welsh literature, but Rhydderch Gwyn is a far more complex and nuanced character than most.

His methods are dishonest, but his ultimate motivation is his genuine love for his innocent daughter, whom he wishes to see accepted by her society, rather than punished because of his own vices.

Folk traditions

As well as this gripping story, the novel serves as a loving catalogue of Welsh folk traditions, superstitions and fairy tales, all of which Vaughan loved, and saw as being in danger of dying out.

These elements—the Cysgodau/Shadows of the title—are all artfully weaved into the action of the novel, rather than feeling in any way tacked-on; and whilst it’s made very clear to the reader that many of the ghosts or magical elements have perfectly logical explanations, others remain deliberately obscure, giving the story a magical, fairytale element that is enormously appealing.

As always with Vaughan, the story is full of complex, dynamic women whose actions are crucial to the plot, such as Sidi and Hagar, gypsy women wronged by Gwyn and out for revenge; Hagar’s accomplices Siani and Susan, and others.

Vaughan’s style is highly distinctive, and nothing like any other Welsh writer beforehand, though it bears similarity to the style of some much more modern writers.

Her novels have a relatively large cast of characters, and the reader is steered leisurely from one scene to another, chapter by chapter.

They are long novels and relatively slow paced, but not—as is the case with some other early Welsh novels—because of a lack of planning or structure: every scene is a deliberate, careful part of the whole.

Crucial events often take place off-stage, to be recalled by characters as they relate them to others, rather than our being shown them as they happen.

Rather than being in any way unsettling, this feels very realistic, and startlingly modern for a Welsh writer of the time: the reader gets a sense that these are characters leading lives of their own, whom we meet only fleetingly; as if we ourselves are a character in the story, never able to be everywhere, and only able to share the perspective of those we are talking to at any one time.

Within this framework the novels’ secrets and plot twists—a given in novels of this era—feel natural and logical—”how would we know that?”—rather than things merely added for effect.

Of her time

Vaughan’s novels have their idiosyncrasies, and there are some elements to them which will appeal somewhat less to readers today.

Occasionally her prose runs rather longwinded, though she is nowhere near as bad in this respect as some of her lesser contemporaries.

Notwithstanding her feminism and her strident advocacy of all things Welsh, Vaughan was something of a conservative in some other respects: her lack of sympathy for Rhydderch’s mistress-turned-wife in Cysgodau feels out of kilter with the way she was otherwise a champion for marginalised women, for example.

Similarly, whilst her portrayal of the Roma—who feature heavily in Cysgodau—is sympathetic, it is also deeply stereotypical. Vaughan was nothing if not a writer-activist, and if her social commentary is usually appropriate to the contexts of her stories, this isn’t always the case: a chapter on the virtues of teetotalism, adding nothing whatsoever to the story, is rather artlessly shoe-horned into Cysgodau for example.

She was also a deeply committed Christian, a fact which clearly shows in her writing, and with which some readers may find it difficult to relate.

Others, of course, will consider her religious perspective a mark in her favour.

Taken together, however, the overwhelming impression one gets when encountering these works for the first time, is to ask oneself: why on earth aren’t they better known?

To say Vaughan has been hard done by the academics would be an understatement. Although popular in her day, as attested by her gushing obituaries, she was also highly thought of by her literary contemporaries, such as T. Gwynn Jones and Richard Hughes Williams.

However, after dying in the middle of her fourth novel, Troad y Rhod, she was very quickly forgotten. Her entries in the Bywgraffiadur and the Cydymaith i Lenyddiaeth Cymru—in which she is described as a pale reflection of Daniel Owen—are perfunctory, and in his influential treatise on the Welsh novel, which won him the Prose Medal in 1948, Dafydd Jenkins dismisses her novels as being formulaic (a criticism with which I simply cannot agree).

This might, to some extent, be a question of fashion—certainly, during much of the twentieth century her ultimately Romantic worldview may have seemed rather passe, and it could be argued that Kate Roberts (in whom one can recognise much of Vaughan’s DNA) did much of the same sort of thing Vaughan had done for women in Welsh literature, but with a good deal more psychological realism.

However, it’s also hard to escape the impression that there has been an element of sexism in Vaughan’s treatment by the academic establishment in the past, a suggestion made by Rosanne Reeves, the author of Dwy Gymraes, Dwy Gymry, a joint biography of Vaughan and her contemporary, Sarah Maria Saunders.

Notably, it was not until 1978 that Vaughan’s novels were discussed in any real length, and that by Thomas Parry—the man who had chosen to include the work of only a single woman in The Oxford Book of Welsh Verse.

In his lecture, Parry accused Vaughan of writing unrealistic female characters: whilst there is arguably an element of truth to this accusation, it has never seemed apparent to me that realism was much of a priority for Victorian novelists.

I cannot believe either that this is a criticism that would have been made of a male novelist writing about women. Rather than bringing Vaughan in from the cold, it seems likely that Parry’s lecture buried her more deeply in obscurity.

Challenge

Fortunately, however, there is a third powerful thing about literary canons: they are always open to being challenged, re-interpreted, and remade.

Gwyneth Vaughan’s work, in many ways, seems likely to appeal more to readers today than it was fifty or a hundred years ago.

Thanks to the tireless efforts of people like Rosanne Reeves at Honno (who have previously published Vaughan’s work), to whom we are very grateful for writing an introduction to our new edition of Cysgodau y Blynyddoedd Gynt, it appears that Vaughan is finally starting to receive the attention her work so obviously deserves.

One can only hope that this continues, and that Vaughan can finally be given her due as a major voice in the history of the Welsh novel.

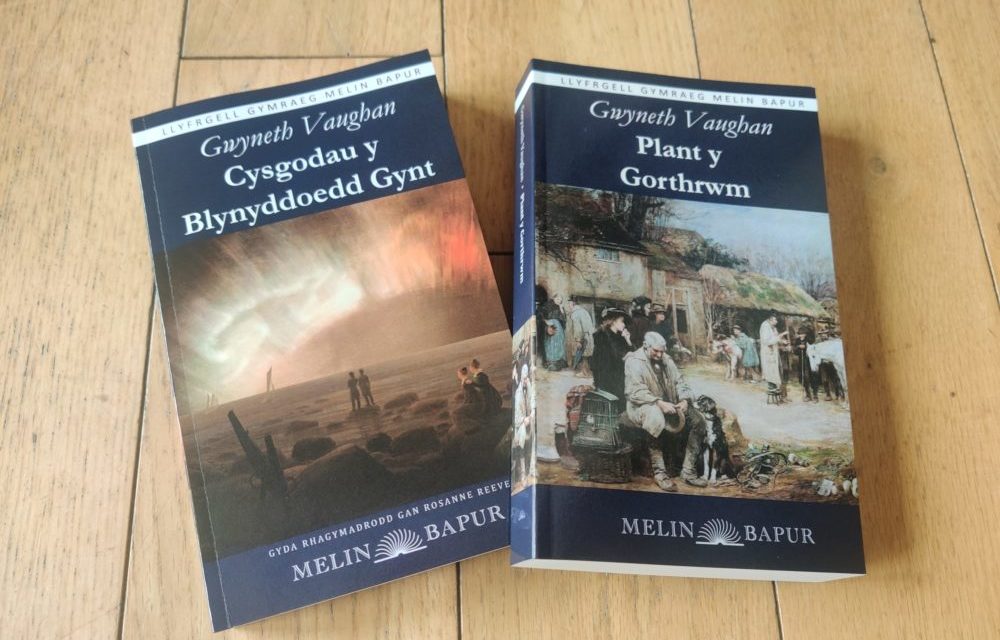

Plant y Gorthrwm and Cysgodau y Blynyddoedd Gynt are both published in new editions this week and available from www.melinbapur.cymru, priced at £11.99 each + P&P.

All Melin Bapur’s books are available as eBooks from many popular eBook platforms. Bricks & mortar bookstores interested in stocking Melin Bapur’s books are encouraged to contact the publisher at [email protected].

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

It is wonderful to see such a recent article mentioning Gwyneth Vaughan. Annie Harriet Hughes was my 3rd great-grandmother and I’ve been long wanting to read her novels. Thank you for such an interesting summary of her work and life.