House of Dogs: The Last Squires of Trecwn Part 13 – Cyril Barham and the Curse of Trecwn

We continue our series exploring the history of a Pembrokeshire estate and its colourful family.

Howell Harris

The details of the Barham family’s private arrangement, and thus of how much Cyril inherited and on what terms, never emerged in public. But the settlement was said to be very favourable to him, though he complained that its terms crippled the Trecwn estate.

This was probably by exhausting Francis’s non-property wealth and perhaps also by charges on the rental income to pay off the Squires, other beneficiaries, and legal expenses.

Cyril compensated for the cost of the two court cases and the Squires’ shares by taking for himself the portion that should have gone to his sisters, who had trusted him to represent their interests. This was a trust he neither deserved nor returned; they were left with nothing.

How to Lose Friends

In early 1929 Cyril and his family finally moved in, exchanging their modest semi in West Ealing for an enormous mansion, its grounds, and the surrounding thousands of acres.

That December they made their first big but probably unwelcome impact on the locality, and certainly on their gentry neighbours.

They prohibited the Pembrokeshire Hunt from entering onto an estate that they had been coming to forever, and which offered the only really dependable supply of foxes in the north of the county.

Cyril and his wife Mary told the papers that they “considered hunting a cruel form of sport, and on no account would they allow hunting over their land.”

The former hunt secretary replied mockingly: the next stupid thing the Barhams would do would be to stop rabbit trapping, and ban the use of steel traps! “Mrs. Barham would rather be a vegetarian than eat meat not killed by a humane killer and is working hard to make humane-killers compulsory”!

They would “mak[e] a nursery for foxes at Trecwn,” or, as the South Wales Argus headlined the story, a “Paradise” for the vermin! They would obviously never fit in where “the noble science of fox hunting” enjoyed more respect than ludicrous opinions like these.

Despite this bad start the Barhams made some effort. Cyril turned from a Mr. into a Captain between his court appearances in 1927 and 1928 and his arrival at Trecwn, imitating his father Lieutenant Robins in this respect if in few others.

Unlike Francis he also did more of what a squire was supposed to, becoming a magistrate and a rural district and county councillor for the Henry’s Mote division, the eastern (Tufton) part of his estate.

And he acted to remove at least one question mark about himself that would have caused embarrassment if discovered by, for example, an inquisitive prosecution lawyer.

In October 1931 he and Mary finally got officially married, in Bournemouth, perhaps in preparation for his next act on the public stage.

This came in January 1932, in his trial at the Pembrokeshire assizes in Haverfordwest on a charge of slander.

His final court appearance, apart from his inquest, would have an even worse outcome than either the perjury prosecution or the attack on his father’s will.

Dripping With Malice: Slandering Dr Howard Owen

The case was brought against Cyril by the local GP, Dr. John Howard Owen, Medical Officer of Health to Haverfordwest rural district council and the fourth generation of Owens to serve Fishguard as a doctor.

Dr. Owen was 45, “happily married, with two young children.”

He had “an extensive practice and a high reputation,” but in the winter of 1930-1931 he became the target of a local campaign of defamation by Cyril that questioned his professional competence and personal integrity.

As his barrister’s opening statement put it, “slander as grave, as malicious, and as malignant as could be uttered by one man of another.”

Cyril’s motivation for this campaign did not become clear or comprehensible in the course of the trial, either in his own testimony or that of others, notably the Barham School headmaster Howard Jones, his father’s old chess-playing friend.

Cyril had told him in April 1931 of his intention “to hound” Dr. Owen and his partner, but not why.

Howard had an explanation all the same: Cyril “would quarrel with his own shadow.”

Cyril was also involved in another potential lawsuit — about the school itself — at the same time, causing the trustees and managers much unwelcome effort, which may help explain Howard’s low opinion of him.

Nor did the actual details of what may or may not have happened, rather than of what he said about it and to whom, ever get clarified in two days’ testimony.

But the allegations were plain enough: that Dr. Owen neglected his patients, at least one of whom had died as a result; even more seriously, that he “had seduced a young female patient, and that he had committed a criminal assault upon the girl.

Further, he said that the doctor had performed an illegal operation [abortion] on the girl.”

What lay behind this? Cyril and his wife had had a young servant, Mary (or May) Lloyd, daughter of a local smallholder and rabbit-trapper, on whom they took pity and who became almost a third daughter to them.

By the time of the trial she was reported as having been with them for two and a half years, and to be seventeen and a half, i.e. she started with them in 1929, shortly after leaving school.

She went to church, the cinema, and on trips with the family. But some time in 1930 she “found herself in trouble at Bournemouth,” where the Barhams had taken her, and came back to Trecwn that November.

“She admitted she had a baby at Bournemouth, and did not know what to do to keep it from her mother.” “When she told him [Cyril] of her condition she pleaded with him not to tell her parents.”

Even the basic facts were never clearly established — when did she go to Bournemouth, and for how long? Having a baby generally takes 9 months, after all.

Had she actually had a baby at all, or had she simply engaged in ignorant and unprotected adolescent sex, missed one or more periods, and returned home beside herself with anxiety?

What mattered was what Cyril said about it, not what had really happened.

Cyril and his wife took her to see Dr. Owen on November 12th “because she said she did not feel strong enough.”

Dr. Owen, with whom, Cyril said, the girl had been “very friendly,” his “pet” (according to Cyril, Dr. Owen had written her personal letters and sent her a photograph), insisted on seeing her by herself, not just at his surgery but on a long home visit on the 18th, or so Cyril asserted.

All of this Dr. Owen of course denied, responding that he had only been her doctor for a year, and had had little to do with her even professionally; that the letter Cyril purported to have been from him was not in his handwriting; and that he had never seen the girl alone at her home, only at his surgery, and then with her parents — all of which they corroborated.

When he saw her in November, his diagnosis had been that she was anaemic. He “had never charged the girl with misconducting herself with any man, neither had he said she was in trouble.”

And then things got really messy. In late November 1930 Cyril got the first of a number of statements from the girl, i.e. he wrote it and she just signed it.

(Or perhaps not even that — when asked by the judge to produce the original in court rather than a copy, his explanation for being unable to was remarkably weak — he must have left it with his solicitors in London; a dog-ate-my-homework quality excuse).

He also started pestering Mary’s parents about her supposed relationship with Dr. Owen and pressuring them to support his campaign.

He accused her mother of “taking sides with the doctor and not with her own daughter” because of her unwillingness to say that something that had not, to the best of her knowledge, happened at all, had indeed taken place just as Cyril stated.

He wrote to Dr. Owen’s wife alleging his neglect of his patients, and visited the doctor’s sick father to complain about him to the old man too.

He even told Dr. Owen face to face, when he went to settle his bill in March 1931, that he would be writing to the British Medical Association to get him struck off.

Given that Cecil was a magistrate and councillor, and formerly a civil servant at the Ministry of Health, this was the kind of threat that had to be taken seriously.

Cyril assembled his “evidence” for the attack. That same month Mary Lloyd “swore on the Bible that the doctor had taken advantage of her” during the long home visit in November which Dr. Owen firmly denied had ever taken place.

Her statements were full of lurid details, including that Dr. Owen had assaulted her while she was under anaesthetic, and strong claims, notably that “she was chaste before she met the doctor,” which makes the story of the Bournemouth baby all the harder to understand.

She never testified in court herself, so any attempt to make sense of her (or “her”) stories is purely speculative, but here is my attempt: when she came back from Bournemouth in November 1930, fearing that she was pregnant because of a missed period after a fling, the story about having been violated by Dr. Owen might have been a desperate invention of hers.

The follow-up story about an abortion might have been a way to explain the subsequent non-appearance of a baby, after either a miscarriage or a late period had ended the pregnancy or worrying about one that never existed.

And both stories might have resulted from or at least responded to suggestions from Cyril. He was a dominant older man on whom she was dependent.

He even drove her to the surgery to collect the medical certificates necessary for her to be able to claim sickness benefit during the time she was signed off work on account of her diagnosed anaemia.

He also had a tendency to explain the world in terms of malign conspiracies, as the perjury trial and his challenge to his father’s will had shown. If he believed that Dr. Owen had been excessively friendly towards Mary, a girl Cyril treated almost like a daughter, that could have been enough to set him off.

Whatever the origins and veracity of Mary’s (or “Mary’s”) statements, in April 1931 Cyril began to spread stories about Dr. Owen in the locality on the strength of them, out of a sense of duty, or so he claimed.

“Letterston is one of the most immoral places I have heard of. Girls of fifteen and sixteen become mothers and think nothing of it.” He was on a mission to improve village morale, as well as to deliver justice to evildoers.

Why did he embark on a campaign of slander to achieve this? Because he was convinced that other pathways were blocked.

He attempted to take out a summons against Dr. Owen on the 26th of March 1931, but the clerk to the Fishguard justices, R.T.P. Williams, refused, telling him to apply at the regular petty sessions on April 3rd.

At that meeting Cyril made a sworn statement to the justices in the presence of the local police superintendent, whom he had already seen.

The Superintendent said that the police were making enquiries, so the magistrates would not grant the summons. At the next meeting, May 1st, the police reported back that the Chief Constable had decided to take no proceedings.

At some point in these discussions Williams told Cyril “You are very silly to do this,” and “the chief constable, before he even opened his mouth, said, ‘It is a serious thing for you.’” But he did not listen.

He had an explanation for their good advice: a local conspiracy against him. “Welshmen clung to one another, … and Dr. Owen had relatives all over the county where he (Cyril) was not known. He knew … when he attempted to take out a summons that he would not get satisfaction.”

He said much the same to the schoolmaster Howard Jones — “he could not get justice in Wales because the people were Welsh.”

This was a pretty fundamental and indeed insuperable problem about which he had complained even before the perjury trial in 1927, i.e. it was a deep-rooted conviction with him. He probably thought the locals only stopped speaking English the minute he went into the village shop, too.

In fact Cyril was the victim, not Dr. Owen. He was a victim, in the first instance, of Howard Jones himself, who had reported his slander. Jones was “‘a dangerous local gossiper’.

He had always been a thorn in his side. He gave evidence against him (i.e. that Francis had been an excellent chess-player) in the action he brought in respect of his father’s will. The action cost him thousands of pounds, which had crippled the estate.”

He “watched him day and night and was doing everything to thwart him. He and the postman had concocted the story that he (Cyril) told Mr. Jones that Dr. Owen had assaulted the girl.”

He was also a victim of Dr. Owen who, most unfairly, had the Medical Protection Society behind him, paying his bills, so could afford to sue him for “a fancy sum of four figures knowing that the action would not cost him a penny.”

Poor Cyril had to face “an array of counsel” (a silk and two juniors) all alone, representing himself for reasons, he said, of economy. To cap it all, Dr. Owen had offered bribes to witnesses to testify in his favour — an allegation that the judge immediately told Cyril that he would have to prove.

But it turned out that Cyril’s witness to Dr. Owen’s attempt to bribe him had in fact already signed a statement that Cyril had bribed him earlier, to testify against Dr. Owen.

“He tried to persuade him to say that on November 18 [1930] he saw Dr. Owen enter the house of May Lloyd and remain there about 55 minutes, that he also told him Dr. Owen was a blackguard and not fit to be a doctor. He took advantage of May Lloyd and gave her a drug to get rid of a child.”

So Cyril’s star witness ended up admitting that he had lied, and Cyril himself denied that he had ever made one of the other allegations he was charged with — that Dr. Owen neglected his patients — though he obviously had, not least to Dr. Owen’s wife, and on paper.

As for Mary Lloyd, surely a key witness, she was nowhere to be seen. Her mother had got at her, complained Cyril, and persuaded her not to appear.

But she would not have been much help to him if she had, because she had already retracted her statements and explained that Cyril had written them and she only signed, something he belatedly admitted under questioning in court.

Dr. Owen’s barrister then proceeded to take Cyril Barham apart. The jury “might call the defendant a squire,” and he “was known as Capt. Barham, but had no right to that title or description.

They would find he was a man of eccentric and quarrelsome character, ‘a man who doesn’t stop and hasn’t stopped at making the most grave and unfounded allegations against people’.”

He brought up the 1927 perjury suit and the 1928 will dispute as evidence that Cyril was a “habitual maker of gross allegations against most people.”

The reason he was defending himself was not, as he had stated, economy, but that he could not persuade any barrister to take on his defence, which was a complicated one: he had not uttered the words complained of; or, if he had, they were justified and indeed privileged.

Cyril almost admitted it — “It was not because of that exactly. There was some suggestion of a settlement then.” If only he had taken his lawyer’s advice, or the magistrates’ clerk’s, or the chief constable’s!

The judge summed up: there was no evidence behind Cyril’s accusations; there was no evidence to support his plea of justification; and when given the chance to withdraw his slanders, he had rejected it.

“They were dealing with a man who had started a campaign and was pursuing it through thick and thin despite the absence of evidence.” Cyril simply threw himself on the jury’s mercy, arguing “that he had acted not on his own behalf but in defence of a young girl.”

Dr. Owen’s barrister would have none of it: Cyril Barham’s case was just “dripping with malice” from beginning to end, and the jury agreed.

It took them only 20 minutes to return with a guilty verdict and a £5,000 award (c. £1.1 million nowadays, presumably plus costs), to the cheers of the courtroom audience.

Dr. Owen’s KC then asked for an injunction against Cyril to prevent any repetition of his slanders, and this was readily granted.

If Cyril thought Howard Jones’s testimony about his father’s chess-playing skills in the 1928 will dispute had cost him dearly, this time Jones had cost him far more.

He had to take out two mortgages on the estate, in March and September 1932, to cover the damage.

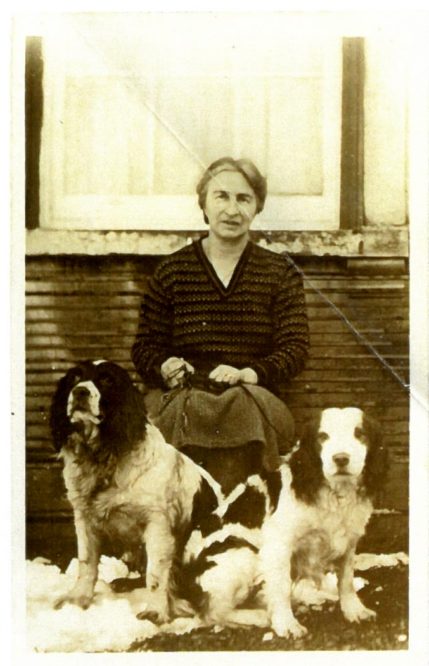

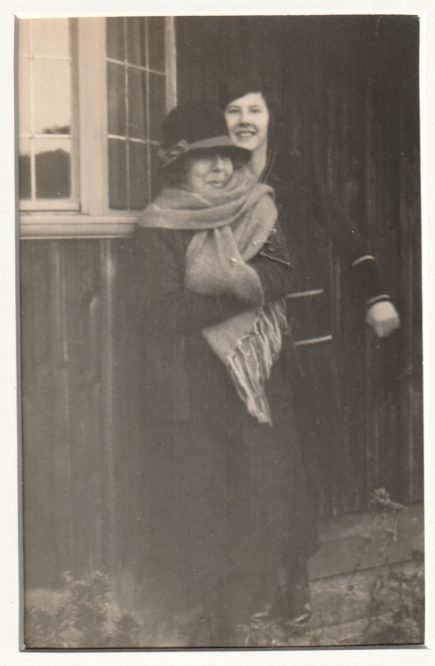

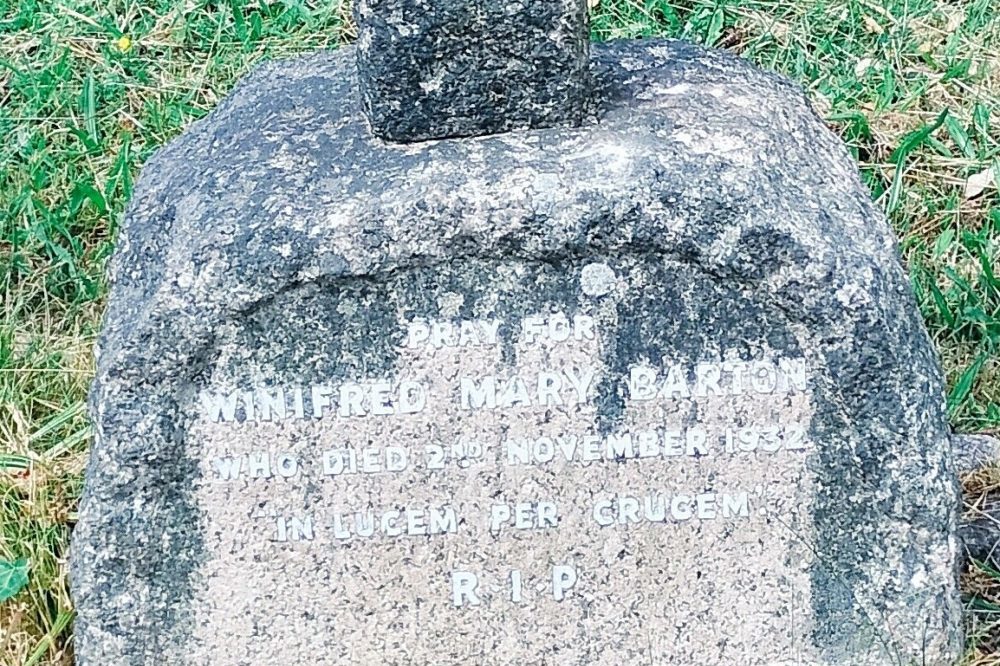

His sister Winifred lived long enough to witness Cyril’s disgrace, but by that time her health was already failing after fifteen years of hard, poorly paid work to support herself and her daughter.

She had to stop nursing, and Cyril made her a less than generous allowance of £2 a week to support her and Margaret until she died in Swansea that November.

Margaret, orphaned aged 15, went to live with her aunt Rita at the Catholic prep school she helped run near Liverpool, where she had to work for her keep.

The Journey to Coventry

Cyril can hardly have found Trecwn, or Pembrokeshire more generally, a very welcoming place after his very costly purchase of even more notoriety than his father had ever achieved.

It is hard to believe that many of his neighbours and associates would not have sent him to Coventry. And how could he have continued as a magistrate and a councillor after this fiasco, unless he possessed an Olympic-standard brass neck?

But at least there was the future of the next generation of Barhams to concentrate on.

They were trying to get their son Cecil into Oxford, and moved to a house on Wellington Square to be close to him, probably while he attended a crammer to prepare himself for the entry examinations.

But things did not turn out well for them in the South Midlands either. On the evening of Friday the 14th of March 1933 the Barham family, apart from their younger daughter Jeanne who was at home in Oxford, were driving home from Wales in their Daimler on the A45 just south of Coventry itself, young Cecil, 19, at the wheel.

The road was excellent, and made for speed. The night was dark but clear, and the road was dry, with no mist.

Just after crossing the River Avon at Ryton Bridge they stopped on the verge on the north side of the road, at the bottom of a long, straight incline that ended with a slight bend or dog-leg.

They wanted to go across to the Knight of the Road (now the Citrus) hotel on the south side for refreshments, before turning off towards Oxford. They left the sidelights on and Cyril, Mary, and Cecil walked around the back of the car and out into the road, which they thought was clear.

Unfortunately two motor engineers, Henry Brooke and George Everett, returning home to Coventry for the weekend from their work at the Ford factory in Dagenham where they lodged together, were coming the other way in their small, light car. Brooke was driving.

They had stopped twice along the way for a pint of beer and then a gin and tonic each, but were deemed to have been quite sober by witnesses and the attending police.

They had their headlights on and were going about 40 mph — their little car could not do more than 50.

They saw the sidelights of the Barhams’ Daimler on the verge opposite and dipped their headlights in response, so they did not see the trio in the middle of the road until they were almost on top of them; they may also have been a little distracted by the hotel’s illuminated sign.

Brooke slammed on his brakes, started to skid, and swerved to avoid them, hoping to go between them and their car.

But the Barhams made the fatal mistake of jumping back in the same direction, so he hit them head on instead.

The Barhams’ older daughter Dorothy, 23 at the time, saw everything from her seat in the back of the Daimler. Walter Miles, the first witness on the scene, spotted Brooke’s car stopped on the verge, and then he too had to swerve to avoid Mary Barham’s body on the road, all except for her head, which was on the verge too.

Miles stopped and saw a dazed Brooke wandering in the carriageway, holding his head and bleeding from his face and neck. “I dimmed my lights; they came from nowhere, he said.”

“Then I got another shock,” said Miles. “The driver said ‘there’s another one over there’ — pointing to his own car.” Young Cecil was impaled on the bonnet, as dead as his mother.

Then Brooke said “I’m sure there was a third.” Miles had a torch, and found Cyril lying on the verge. He had severe injuries to both legs, one arm, and his head. He never recovered consciousness and died later in Coventry hospital.

The inquest verdict on the three Barhams was Accidental Death. Brooke was sober, his speed was reasonable, his reaction was appropriate, there was nothing more he could have done.

The Curse of Trecwn

The Curse of Trecwn had struck again, and for the last time.

The Barhams could trace their descent and their ancestors’ tenure of Trecwn all the way back to Owen ap (son of) Dafydd in the early sixteenth century, and beyond him to a fourteenth-century chieftain, Llywelyn y Coed (Llywelyn of the Wood), progenitor of several Pembrokeshire gentry families.

Owen ap Dafydd ruthlessly destroyed many dwellings to improve his lands for hunting, so one old hag, reputed to be a witch, cursed him and his descendants.

Though the land would remain theirs, the name of its occupants would change constantly, because of a lack of male heirs. This had happened repeatedly over the centuries, including to the Barhams. It would never happen again.

Cyril left £47,136, Mary £7,890, i.e. despite his considerable legal expenses they were still quite rich, and their daughters would not go hungry.

Dorothy would have the complex task of being administratrix of their intestacies, and then owner of the rump of the estate, to keep her busy for years afterwards.

In the next episode we will find out what she and her sister did with the heart of the estate, and how its new owners for sixty years from 1936, the Admiralty, transformed it.

You can find the rest of this series here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.