House of Dogs: The Last Squires of Trecwn Part 16 – The World We Have Lost

We reach the end of our series exploring the history of a Pembrokeshire estate and its colourful family.

Howell Harris

There is little point speculating about the future of Trecwn, though a reasonable forecast is that it will probably be an indefinite extension of the last thirty years.

This is perhaps the best outcome, given that nothing that has been proposed thus far would bring us any closer to a better one.

It would just extend and make more permanent the industrialisation of an area of great natural beauty that would never have been developed at all but for the particular requirements and absolute powers of the Admiralty.

So instead I will end with an alternative future that never happened, but could have, and elements of which might still be retrievable.

If the Depot had never happened…

The Admiralty surveyors prowling the county in the mid-1930s reached the somewhat regretful conclusion that the site was unsuitable, despite its attractions of topography and geology.

It was just too isolated, and in the wrong way, i.e. not just from German bombers.

Assembling and maintaining a workforce, supplying the site, and transporting munitions in and out of the depot to where they would be needed, were challenges that could be avoided by locating the depot closer to centres of population near the western part of the coalfield.

So the Barham sisters carried on as the estate’s reluctant owners, administering it from afar and trying, without much success, to sell the least profitable parts of it, while renting out the rest.

Guy Noott stayed on as the Mansion’s tenant until the war dislodged him. It was commandeered to serve as the temporary home of a school evacuated from London in 1939, and then as a special forces training base, so by 1945 it had been knocked about a bit.

But at least it was still standing, and could even look forward to a brighter future.

The National Park Idea comes to Pembrokeshire

In summer 1945 the new Labour government inherited an issue that had been bubbling away through the 1930s and achieved, surprisingly, higher priority during the life of the wartime coalition government.

Establishing a system of National Parks, for purposes of landscape preservation and popular recreation, took its place as an important part of the better Britain that progressives from across the political parties were intent on building.

Labour was bequeathed a blueprint for this system from the coalition government’s work, in the shape of the Dower Report of May 1945.

They also inherited a new National Parks Committee tasked with visiting areas John Dower had identified as priority candidates for the establishment of national parks, and making recommendations about “special requirements and appropriate boundaries.”

After initial meetings in London in early August, the Committee broke into sub-groups that spent 85 days over the next couple of years on 17 inspection tours to the Parks of the future.

The Pembrokeshire sub-committee spent four days in the county later that month, and on their last day they were scheduled to visit the Preseli mountains.

They were made welcome by local supporters of landscape and nature conservation, notably Ronald Mathias Lockley, the county’s leading naturalist and an eloquent supporter of the National Park idea for at least a decade.

The visitors were all members of the Great and the Good, men in their fifties or early sixties at the peak of their careers; three of them had even attended the same Cambridge college, Trinity.

The chair was Sir Arthur Hobhouse, leader of the County Councils Association and president of the Open Spaces Society.

His colleagues were Leonard Elmhirst, a West Country landowner like Hobhouse and a philanthropist with a particular interest in countryside development and forestry; Julian Huxley, Eton and Balliol, an eminent zoologist and long-standing friend and collaborator of Lockley’s and lover of Pembrokeshire’s natural scenery and wildlife, who had just been appointed as the founding head of the new United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO); and the architect, landscape preservationist, and tireless campaigner Clough Williams-Ellis, the only Welshman among them and an advocate of National Parks in and for Wales since the late 1920s.

They were supported by a dedicated secretary, John Bowers, and, on the Pembrokeshire leg of their trip, were also accompanied and advised by John Price, the County Council’s planning officer, a role he would also fill for the Pembrokeshire National Park Authority for its first quarter-century.

Price was a dedicated landscape preservationist in his own right, and an unsung hero in the battles of the previous decade to conserve the county’s finest scenery.

The movement for a National Park in the county since 1930 had focused narrowly on coastal protection.

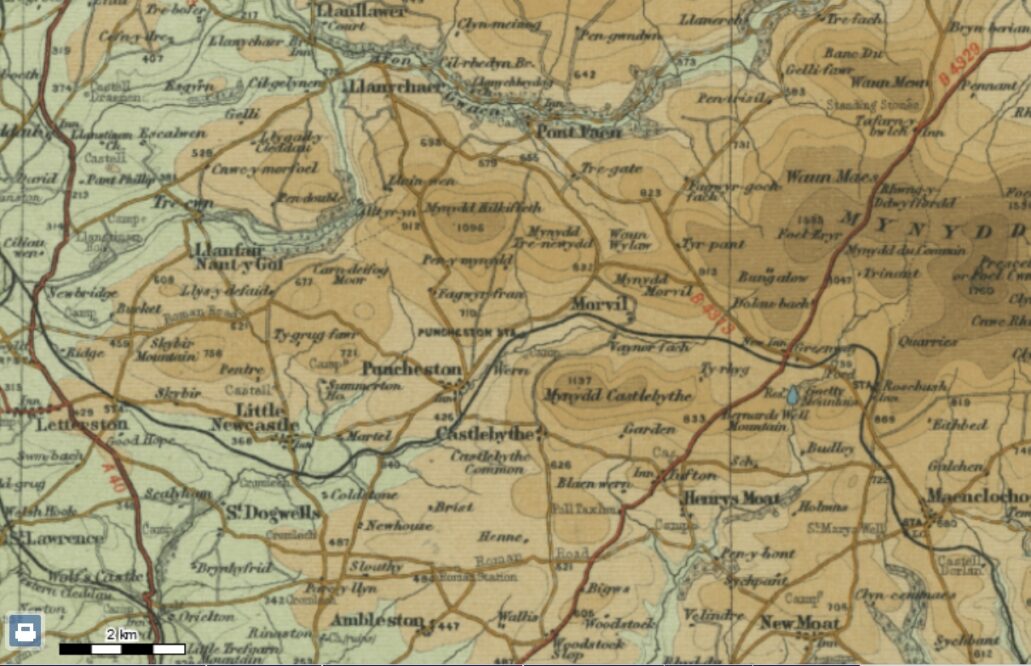

Even in the Dower Report all that was envisaged was a belt a mile or more across, starting west of Tenby, leaving out the Milford Haven entirely, and also excluding Fishguard and its immediate surroundings.

It would have been far and away the smallest of the National Parks, little over 100 square miles.

And by 1945 that coastal belt was badly compromised — with the Royal Artillery establishment at Manorbier, the huge tank training range at Castlemartin, and numerous other abandoned military installations around the coast, the remains of which would take decades to clear up.

But Ronald Lockley and Julian Huxley had bigger ideas, a way of compensating for the spoliation of the coast and also fending off the threat of further land-grabs by the armed services.

The Army had its eye on the whole of the Preselis for an artillery range, a menace that stimulated Waldo Williams, perhaps the greatest Welsh poet of his time, to write one of his finest poems in protest, “Preseli” (1946), with its famous last line: “Cadwn y mur rhag y bwystfil, cadwn y ffynnon rhag y baw.” [“To the wall! We must keep our well clear of this beast’s dirt.”]

Waldo need not have worried. Lockley and Huxley had already mounted a preemptive strike to try to spike the beast’s guns.

Lockley had lived in the county since 1927, mostly on the island of Skokholm until the Royal Navy required him to evacuate after the start of the war, the rest of which he spent farming at Dinas Island near Fishguard.

He knew every inch of the county, including one of its least-visited areas, the Daugleddau — the tidal Cleddau and its offshoots with their beautiful oak woodlands — where he had spent several winters away from his island in the early Thirties.

Huxley had visited the county for decades, particularly since his collaboration with Lockley began in 1933, and deepened with their founding of the Pembrokeshire Bird Protection Society in 1939.

He kept coming right through the war years, holidaying with or near the Lockleys, most recently to get the peace and quiet he needed for drafting UNESCO’s statement of purpose.

By the mid-1940s he shared Lockley’s appreciation of the landscape, wildlife, and antiquities of the north of the county, and together they made a bold pitch to the National Parks Committee: the Pembrokeshire National Park should include a large chunk of Preseli and the whole of the Daugleddau, more than doubling its size.

The decision, however, would be the Committee’s. For the first half of their four-day visit they stayed at Lawrenny, so they had plenty of time to appreciate the Daugleddau; for the second at Dinas, with the whole of the last day, the 24th of August, scheduled for a tour of inspection of the north coast as far as the Teifi, and also the Preselis.

But, one after the other, all of the cars in which they were supposed to travel broke down — this was the end of the war, when private vehicles were old and tired — so they never got to see Preseli or anywhere else away from the coast.

No matter — over a rabbit-pie supper in Lockley’s farmhouse, immediately after the founding meeting of the West Wales Field Society (the new incarnation of the Pembrokeshire Bird Protection Society, and ancestor of today’s Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales), the other three committee members agreed to endorse the whole of the Huxley-Lockley proposal.

This was not the end of the story — their recommendation had to go before the full committee, it would be subject to consultation and modification even after inclusion in the committee’s final report in 1947, and the decision-making process would take years before the official designation of the Pembrokeshire National Park within, essentially, the boundaries Lockley and Huxley had sketched out. But the die was cast on that August day in Dinas, and a third of the county’s land area would eventually enjoy the limited protection that National Park status provided.

The Valley joins the National Park

The previous part of this story is all true, though unfamiliar. But in the future that never happened, in 1945 Trecwn was still available for inclusion within the Park’s designated area, rather than absolutely ruled out and still covered with a blanket of secrecy, as it was in fact.

Why did the valley deserve designation? Not just its natural beauty and wildlife, but the reason for its grandeur — its high, steep sides that appealed so much to Admiralty surveyors.

The vale of Trecwn was not cut by the streams or small rivers that flow through it now, but by glacial meltwater at the end of the last Ice Age.

The gorges of the Aer and the Cyllell are a key feature of the Gwaun-Jordanston meltwater channel system, in Brian John’s words “one of the most spectacular in the British Isles,” and though Nant-y-Bugail is not the largest of these channels (that is the Gwaun itself), it is the deepest.

The Park would not stop as it now does at the valley’s northern security gate, which would not of course exist.

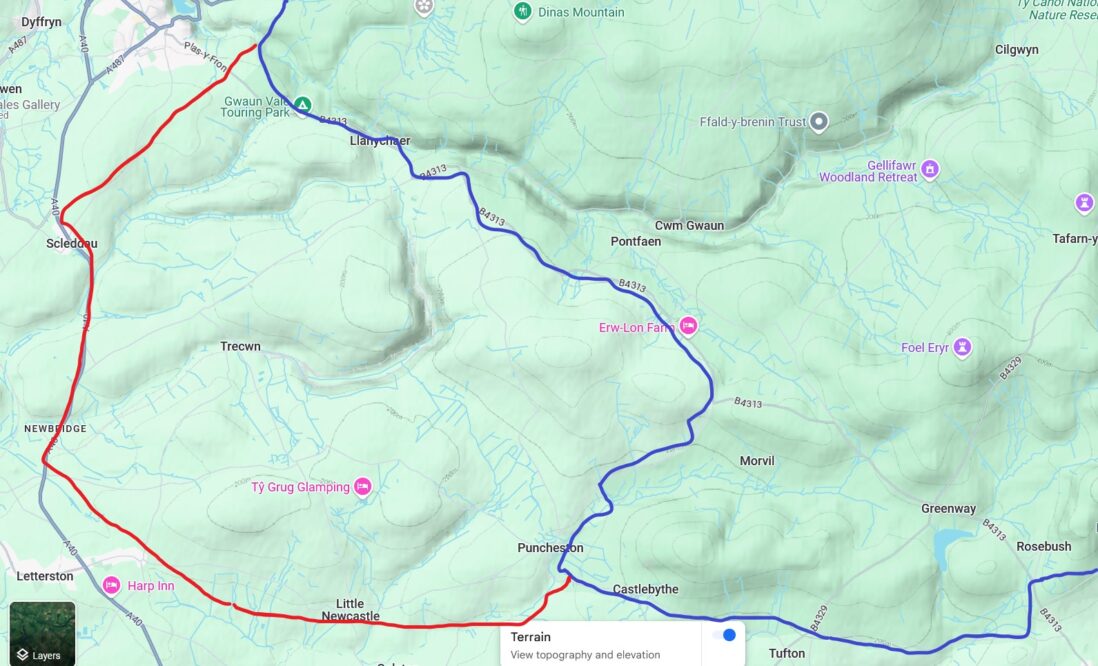

The valley would instead be one of the Park’s most cherished inland areas, crossed by a walkers’, riders’, and cyclists’ path running from the Gwaun at Llanychaer all the way through the gorges of the Aer and the Cyllell to Trecwn.

Perhaps it would be called the Lockley Trail, recalling the route of his last visit in December 1936 (which would not of course have been his last).

And when Lockley looked for a new home in the early 1950s he might not have settled on the dilapidated Georgian mansion at Orielton, in the south of the county; he could have found the equivalent challenge and reward much closer to home, at Trecwn.

The world might have been deprived of The Private Life of the Rabbit and, in due course, of his friend Richard Adams’s Watership Down; but The Private Life of the Otter would have been ample compensation.

And Trecwn’s greater distance from the industrial development of the Milford Haven that began in the late 1950s might even have persuaded him to stay in the county rather than to escape the refineries and power station by leaving a couple of decades later.

In my semi-alternative history, when Lockley finally packed up, whether through old age or death, the Mansion could have become, as Orielton did in real history, a Field Studies Centre, bringing students and other visitors to appreciate the natural beauty and wildlife of the valley itself and its North Pembrokeshire surroundings.

And when the Field Studies Council could no longer make a go of it, perhaps it might have been snapped up by Harry Handelsman, fresh from his experience of turning the Chiltern Firehouse in central London into a successful hotel and looking for new challenges and opportunities.

He certainly appreciated the Mansion’s wonderful location as much as Ronald Lockley, Richard Fenton, and John Wesley had, and saw its future as a country-house hotel, a 12-month destination like The Grange in Narberth or Lamphey Court, and the centrepiece of a much larger development of the valley’s possibilities for green tourism.

The walking trail would start from one of Lockley’s greatest legacies to the county — the Coastal Path, which he surveyed and laid out — and march across the hills from Dinas Cross to the Gwaun.

It would extend beyond Trecwn to link up at Letterston with his unrealised dream, the transformation of the old North Pembrokeshire and Fishguard Railway’s abandoned track, finally closed in 1949, “which wandered delightfully along the southern foothills of the Presceli (sic) Mountains,” into a “linear nature reserve (which it had already become), making the inland boundary of the new Pembrokeshire National Park.”

The old railway did mark that boundary between a point just north of Maenclochog and Morvil, but there the original park boundary struck north until it met the B4313 from Rosebush to Fishguard along which it ran north-west, and eventually down the lower Gwaun.

But in this lost future the boundary would have followed the railway down the valley of the Anghof to just south of Little Newcastle, then across country almost as far as Letterston Junction, and along a short section of the A40 as far as Scleddau where it would have turned north-east to reach the Gwaun a mile or so outside Fishguard, where the actual Park boundary lies.

The valleys of the Cyllell, the Aer, and the other smaller meltwater channels of the Gwaun-Jordanston system in the headwaters of the Western Cleddau, the Criney and the Esgyrn, would all have been safely enclosed within it.

Even in the real world of Britain at the end of the Attlee government, with Trecwn and its surrounding hills and valleys unavailable for inclusion in the National Park, the dream of a linear nature reserve from Rosebush through Puncheston and Little Newcastle to Letterston was still possible.

Lockley’s friend Sir Cyril Hurcomb, chairman of the British Transport Commission and a fellow naturalist, was very supportive.

But the Treasury overruled Hurcomb’s “fancy plan” to sell or lease the trackbed and right of way to the West Wales Naturalists’ Trust or the new National Park Authority, which in any case lacked the funds to buy it, and instead it was sold piecemeal to local landowners.

So what might now have been one of the finest level walking and cycling routes in the country, a green magnet for slow tourism meandering along the southern edge of the Preseli hills, and perhaps extending all the way down the beautiful Eastern Cleddau valley to the railway main line at Clynderwen, died in the womb.

Enough of lost dreams. We are where we are.

But perhaps the valleys of the Cyllell and the Aer could still find themselves a better future than as a decaying reminder of their fifty unlikely years as a hive of a peculiar sort of industry, never to be revived, and blighted by a continuing series of unfortunate development proposals destined never, with luck, to come to pass.

You can find the rest of this series here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.