House of Dogs: The Last Squires of Trecwn, Part 6 – Peasants against Pheasants

We continue our series exploring the history of a Pembrokeshire estate and its colourful family.

Howell Harris

Most of Francis’s local arguments that ended up in the courts were more serious than the piddling contract disputes we encountered last week.

They related to his role as squire of a big sporting and agricultural estate, the upper-class English proprietor presiding over a small, scattered community of Welsh tenant farmers and labourers.

His land dominated the adjoining parishes of Llanfair Nant-y-Gof and Llanstinan, where he was separated by class, wealth, religion, and language from his couple of hundred neighbours, most of whom were his tenants and/or employees.

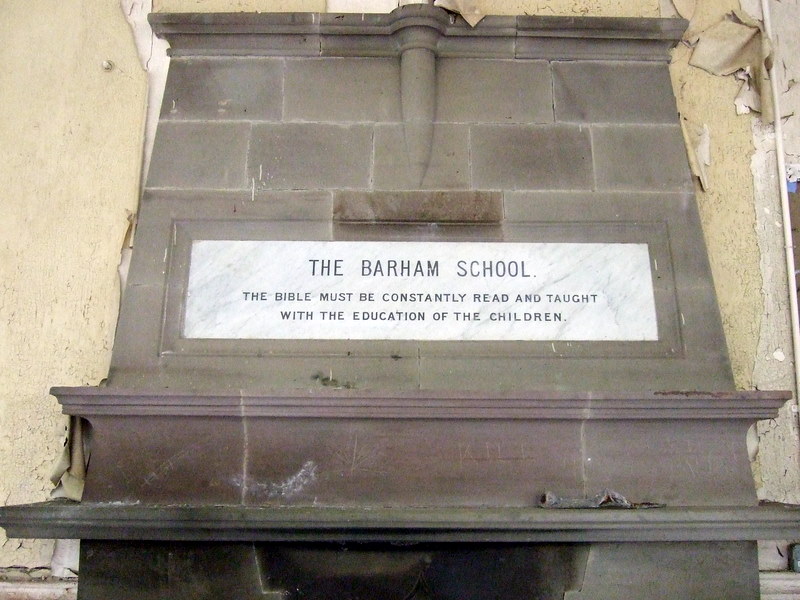

Trecwn had a mansion, a school, a church, a chapel, a post office, a shop, and a mill, and little that happened was free from Barham influence or outright control.

But by the early 1900s that control, and the way it was exercised, was contested. In this and the next two episodes in this series we will read about the resulting years of bitter confrontation that set Captain Barham and his nearest neighbour, the schoolmaster David Bonvonni, at one another’s throats, in a vendetta that lasted until the end of their lives.

David Bonvonni’s Road to Trecwn

Poaching was the biggest cause of conflict between the Barham estate and its tenants and neighbours. Protecting game, especially the pheasants but rabbits too (the key prey for the precious foxes), was keeper Fred Bogg’s duty, and he was very diligent in carrying it out.

In this he was ably assisted by the local magistrates.

Rigorous enforcement of anti-poaching laws, though, came up against locals’ need to trap rabbits for food, to protect their gardens, or for extra cash, and farm tenants’ rights to ground game.

And in 1906 Fred Bogg encountered a Trecwn resident who was not prepared to defer to Francis’s rule.

This was David Evans Bonvonni, the new and progressive head teacher at the excellent Barham School, which meant that he was Francis’s nearest neighbour.

Beyond the schoolhouse, a couple of hundred yards further up the lane from the village, there was only Trecwn and its grounds, and the mansion’s woodland belt wrapped around them both.

David Bonvonni was a newcomer like Francis, but not such an outsider. He was born in Abergwili, Carmarthenshire, in 1864, son of a Crimean War veteran who joined the Glamorgan Constabulary after being demobbed from the Grenadier Guards.

His way into the profession had been as a pupil teacher, the common route for a poor boy, but he had been fully qualified since the mid 1880s and worked in England for the next fifteen years.

Wherever he taught he was praised for his innovations, notably providing evening classes and practical or technical education. From 1893 to November 1902 he was headmaster at the Hoo Board Schools, outside Rochester in Kent, with his English wife Kate, also a teacher, assisting him.

They were an ambitious and self-improving couple. He took classes in the sciences at the local technical college, and his wife studied for an external degree at St. Andrews.

Bonvonni was a “joiner” and an activist — clerk of the parish council, organizer of the annual athletics competition, a Master Mason — but also sometimes too outspoken for his own good.

He was summarily dismissed from a job at Isleworth almost as soon as he started it, moved a vote of censure against his own Vicar in Kent for not giving a decent funeral to a parishioner he called a “heathen”, and was an active member of the National Union of Teachers.

In 1902 he and his wife were both fired by the school board without explanation — perhaps because of his union activism or his religious unconventionality, or both — and they had to find another job and a home for their growing family.

They bounced back quickly. He was appointed headmaster of Bwlchygroes school deep in the north Pembrokeshire countryside, about 20 miles east of Trecwn.

Teachers’ salaries in Pembrokeshire were poor — even headmasters only averaged about £100 (£49,000) a year — so jobs were comparatively easy to come by, even for a man sacked in mid-career for no stated reason. The local teachers’ union president described the county as “the knackers yard of professional failures.”

David fitted straight into the small community, getting the church organ repaired for the first time in years, playing it and conducting the choir at a splendid Harvest Festival where the Reverend Rees, vicar of Letterston, presided — a useful man for a newcomer to impress.

He brought his forward-thinking into this backwater, along with his hobbies of photography and nature study. He shared his specimen collections with his students and presented well-received, lantern-slide illustrated talks to packed local audiences.

David taught and lectured in both tongues, which his community appreciated greatly. He quickly brushed up rusty recollections from his childhood in Abergwili, Clydach, and Gowerton to become fully fluent in Welsh even when addressing large audiences about specialised subjects.

When he left at the end of 1903, headhunted, perhaps thanks to the Reverend Rees, also rector of Llanfair Nant-y-Gof, to fill a vacancy at the prestigious and well-endowed Barham Memorial School in Trecwn, he was given a splendid send-off by the villagers he had served for such a short time. They knew how much they were losing.

The Bonvonnis settled easily into their new home, in the impressive front portion of the school itself. The Barham was described by admiring local teachers who came to visit them there as “about the finest and best equipped for educational purposes of any in West Wales. Many a college has no more beautiful class-rooms and surroundings.”

They themselves were superbly qualified and “deservedly held in the highest esteem.”

They had only been present for two terms by the time they received their first of many excellent reports from His Majesty’s Inspector for their “vigorous and intelligent” teaching; and their professional peers showed their confidence by electing David, though newly arrived, as their union branch treasurer and delegate to the national union’s conference.

The community, too, welcomed them with open arms. The Bonvonnis and their pupils quickly joined in the round of concerts and other amateur entertainments that were a big part of rural church and chapel life at the time.

David and Francis: Honeymoon and Falling Out

In the beginning David and Francis — who had negotiated and witnessed his contract, because he was the squire and therefore the senior school manager as of right — got along well. Francis was of course chairman of the parish council; David became his clerk, and they cooperated in negotiations with the county council about school funding and other matters.

They were also both Masons, attending the same Fishguard lodge, of which David, characteristically, soon became an officer.

In July 1905 Francis welcomed a day visit from the County School Naturalists’ Club to the school and his estate, letting the Bonvonnis’ guests wander freely and providing them with tea at the mansion.

Francis even gave David a special privilege: he could trap the rabbits eating their way through his cherished vegetable garden, without having to worry about falling foul of the gamekeepers.

David was a dedicated gardener, winning the rare prize of a distinction in the Royal Horticultural Society’s demanding general examination in 1908, the only Welsh candidate to do so, and competing in the annual local horticultural show. He won the prize for honey in the comb in only his second year at Trecwn — appropriate for the future president of the county bee-keeper’s association.

So for him the school’s large garden was one of the major perks of the job, and, thanks to Francis’s generosity, he could keep it safe.

Game Wars and Radical Revolt

This brief honeymoon would soon end. In 1904 Francis appointed a new gamekeeper, Fred Bogg, whom we have already met; and by 1905 Fred was objecting to David and his sons’ rabbit trapping on the edge of the mansion woods, anxious that they might snare a straying pheasant.

However, Francis did not formally withdraw his permission — this, at least, was their understanding — so the Bonvonnis never altogether stopped trapping, though they did keep clear of the woods.

Then in September 1906 Fred Bogg finally pounced — not on David himself but on his 12 year-old son Morris, who was taken before the Mathry magistrates and fined 10s and 15/6 costs — £590 in current money; almost a week’s wages for his father.

The case rested not on the undisputed fact that Morris had been trapping rabbits but on whether Francis had ever withdrawn his permission, about which Morris and David said one thing while Fred Bogg and his assistant said the opposite. David claimed never to have been told; and, if he had had a letter from Francis, it was illegible (the magistrates’ clerk could not read the letters either).

But the magistrates ignored his evidence and arguments, and David exploded with paternal fury. He did not just appeal against the sentence, he went on the attack in a letter to the local paper:

I denounce this selfish mania for the preservation of game …for the purpose of destruction. We, country folks, are warned off from the quiet woodland ways, even the road leading to the school is labelled up “Private road.” My school children are prohibited from entering the copses to gather wild flowers; and for this are enclosures made fitted up with barbed wire fences all around the school premises.

For this curse was my little boy — delicate in health — brought up for sentence before a tribunal of game-preservers. … Our roadsides here are disfigured by impudent notice-boards, telling our children, in arrogant language suitable to the Philistine, that “all trespassers will be prosecuted, all dogs destroyed, and cattle impounded.” … Such is the “land of Gwalia under the rule of the game-preserver.”

A fortnight later he was back in print, widening his attack:

[I]t is not only the game laws that need abolishing; our county magistrates, drawn from the landowning and game preserving classes, are obviously the very last people to sit in judgement on trespassers and poachers.

No one can knock it into the heads of these justice shallows that it’s better to preserve human life in the country than partridges, and that peasants are of more importance than pheasants.

The … sooner we are freed from the tyranny of such village tyrants the better for the community at large. … I for one will always lend my willing help to remove such laws which disgrace the Statute Book and curse the rural life of the people.

So his argument was not just with Fred Bogg, it was with Francis Barham himself and the entire local establishment of which he was a member, and became overtly poitical.

David Bonvonni was a radical Liberal — he had, for example, denounced religious tests for staff selection in Church (then termed “non-provided”) schools as “a farce” at Lloyd George’s great Fishguard meeting on “The Education Question” in September 1905, an intervention earning Lloyd George’s particular approval.

This was an unusual position to take for a practising Anglican and school headmaster who had had to pass and apply precisely such tests in his career.

The great issue in Welsh politics in the run-up to the 1906 general election was the requirement in Balfour’s 1902 Education Act for ratepayers to pay to support Church (and Catholic) schools in which religious instruction took place. Nonconformist Wales was fired up against any such iniquitous imposition.

David’s answer to the problem was drastic, but consistent with his earlier opposition to religious tests: “the only solution of the present education deadlock is purely secular instruction in all public elementary schools,” i.e. the abolition of schools like his own.

“Religious teaching was quite out of place in day schools, and ought to be taught at home.”

This was an awkward argument to make for the headmaster of a school whose motto was “Laus Deo” and where the patrons’ instruction that “The Bible must be constantly read and taught” was literally carved into the stone of the building. The pseudonymous author of a letter to the editor of the County Echo cannot have been alone in seeing the inconsistency.

Turf Wars, Game Wars, and Rights of Way, 1905-1909

David and Francis were embarked on a bitter conflict that would culminate fifteen years later, with David’s enforced early retirement. This enmity showed itself in many ways. Two of them seem almost trivial, but they were a harbinger of much worse to come.

In June 1905 Francis wrote to the editor of the County Echo objecting to the fact that David had been referred to in recent coverage (of which he got far more than Francis) as “`Mr Bonvonni, Trecwn.’ It should be Mr Bonvonni, ‘Barham Memorial School,’ Trecwn, and not Trecwn alone, as that is my address.”

But the papers, and David himself, kept using the objectionable short form — not all the time, but probably too often for Francis’s comfort. As if anybody in Trecwn could be better known or more identified with the place than the squire!

Then on the 2nd of February 1906 two of Francis’s workmen came to the school at 8-30 one morning to cut the chain to the school bell. David asked them to leave and told them that Francis had no power to order it.

This was the manifestation of a dispute that had been running for more than a year. The problem was that the ringing of the school bell disturbed Francis’s peace and quiet at the Mansion five minutes’ walk away, where he often stayed in bed all morning reading.

The two men’s approach to this argument illustrated that they both thought the school was their property. For David, it was his home, his place of work, his small domain; for Francis, just another part of the estate which he had every right to control.

Rights of Way at Trecwn

Neighbourly tensions broke into the local newspapers at regular intervals thereafter, particularly after the poaching dispute. In March 1907, for example, the County Echo reported on a revolt against Francis’s authority at the parish council, where the Reverend Rees took the chair in his place and all present (except Francis) voted in favour of the Rector’s motion, seconded by David:

“That this parish meeting … does not admit that the road leading from Treforvol Farm, past Trecwn, to Llanychaer, is a private road and it hereby calls upon Mr Francis Robins Barham, of Trecwn, to remove the notice boards, and further declares that it is a public right-of-way.

This resolution applies to all the paths in this parish as well.” A copy of this was demanded by Mr Barham and given.—The Rev. J. Rees spoke strongly on the stoppage of the right of way, and bore out his statement by quotations from the Act of 1894, and if the wishes of the parishioners were set aside, the District Council and the County Council would be appealed to.

It probably had not helped Francis keep the Rector as an ally that, a few months earlier, he had sued him for using the coach house at a farm next to the church to stable his horse when he came to hold a service. Rees and his predecessors had been doing so for fifty years, but Francis wanted it for his coach and horses when he came to church.

Threatened with a Chancery case for “wrongful entry and user” and an injunction and bill of costs, the Reverend Rees had no option but to give way in January 1907 and promise never to trespass on Francis’s property again.

His opportunity for payback came quickly. The parish council revolt was a direct attack on the key defence of the estate’s privacy and its precious game’s security: Francis’s claim that the whole of the lane through the valleys of the Cellyll and the Aer to the east of the hamlet of Trecwn, and all of the paths across it, were his, and that only people who had his consent — even the children at the Barham School — could enter his domain. (The lane was also, perhaps incidentally, the most direct route to the nearest pub, at Llanychaer.)

How was this conflict resolved? Francis gave way, and David Bonvonni won.

In 1916 Henriette Miles complained about the result: Bonvonni, “a rabid Socialist, thinks he has as much right on the estate as the owner. … he is constantly parading up & down the road right in to the gates in a most offensive manner & to avoid friction, Capt. B. stays in the grounds, practically a prisoner.” Bonvonni “& some of his families were always on our road, one cannot stop them as he will argue that there is a right of way.”

So it seems that Francis swallowed his defeat, but it certainly stuck in his and Henriette’s throats, particularly because David rubbed their faces in it.

The Llanstinan Rights of Way Case

In the only local access issue that did reach the courts, Francis was the plaintiff, not the defendant. This happened in 1910, and he was acting to secure his tenants’ freedom to use a customary right of way over the estate of some new neighbours at Llanstinan a couple of miles to his west, who had blocked it by felling trees across the lane to prevent people coming too close to their mansion.

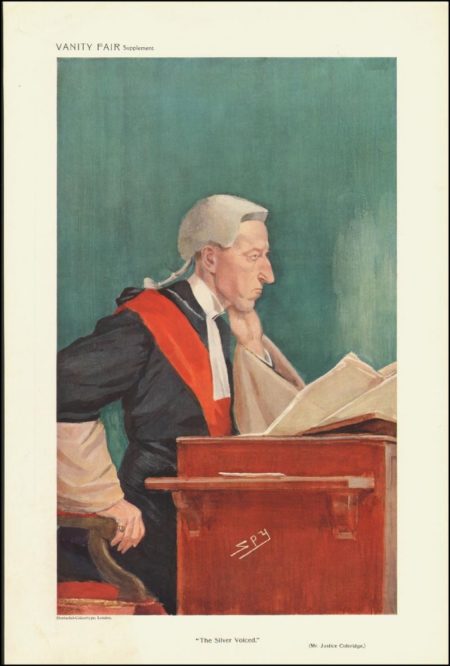

Francis won, in a case that drew a large audience and was widely reported for its fascinating testimony. The judge’s difficulty with Welsh witnesses and place names, even with the help of a translator, was also a great source of amusement. Lord Coleridge, ‘The Silver Voiced,’ “with a despairing gesture said, I pant after you in vain.” (Pant is a common Welsh place name.)

The only way he could follow ancient peasants’ minute recollections of the precise routes they had followed half a century ago driving their cattle to market, or going on errands, or carrying corpses to funerals, was with the aid of a numbered map.

In this case David gave evidence against Francis and his tenants. Lord Coleridge was not persuaded. “[T]he schoolmaster Bonvonni did not appeal to him. He hardly liked to say that Bonvonni was shifty, but he gave him the appearance of a man who wanted to score off counsel rather than give really sensible evidence.”

The county Guardian’s columnist was equally unimpressed. David had “made the great error of ‘trying to be too clever’.” An approach that went down well enough with his usual Pembrokeshire audiences was out of place before a High Court judge.

David’s willingness to testify against Francis’s interest in the Llanstinan case, even though he was in principle an advocate of free public access, demonstrates how bad relations between them had become.

The Vendetta Continues

There were other examples of the same hostility.

In 1908 David had been a key witness (and also the agent provocateur — he told the complainant what he alleged Francis had been saying about him, to get him fired up) in a complicated action for slander and malicious prosecution against Francis by one of his tenant farmers, a neighbour to them both. This was in its origin yet another case of Fred Bogg’s zealous enforcement of the game laws, and was another (partial) defeat for Francis.

Then in 1909 David was even happy to testify in young John Bogg’s favour in his successful unpaid-wages case against Francis.

Why the sustained hatred? Not just the prosecution of his son Morris in 1906, but another incident in 1908, which was all over the local papers because of its “Remarkable revelations regarding the relations existing between two of the most esteemed residents of the picturesque little village of Trecwn.”

David Bonvonni and Levi Miles of Pendouble Farm, a deacon of the chapel, Francis’s tenant, and immediate neighbour to both of them, made several wild claims and counterclaims against one another. But at the heart of one of them was another accusation against David and his son of rabbit-trapping in the field next to his garden where “Capt. Barham had given orders that no one should trap.”

The keepers’ intervention to enforce that order produced a typically vehement eruption from David — the School was “an awkward place to live in and if he were prevented from setting traps he would shoot every pheasant he came across.”

“[A] person might as well live in [Hell] as live there as permission had been given by Captain Barham and had never been withdrawn.” “He would buy a gun and shoot everything he could see, and witness could tell Captain Barham what he liked.”

Both cases were dismissed, as was David’s claim for costs “on the ground that he was a professional man.”

There were no more reported poaching cases after then, but this was not because David and Francis buried the hatchet, though David later claimed that they had. It was more likely because Francis fell seriously ill and rented out his shooting to another gentleman who did not live nearby and whose enforcement of the game laws may not have been so rigorous.

Next week we will pick up their arguments in 1916, by which time Francis, 75, was at last recovering his health and David, 52, came perilously close to ending his life.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.