House of Dogs: The Last Squires of Trecwn, Part 7 – The Battles of Barham School

We continue our series exploring the history of a Pembrokeshire estate and its colourful family.

Howell Harris

Francis Barham and David Bonvonni, neighbours at war, had one further meeting in court to look forward to.

The Assault

On Tuesday the 29th of August 1916 Francis was entertaining house guests at Trecwn — Henry Isaac Cundy, b. 1879, an architect and surveyor he had known for 15 years, and appointed as one of his executors in 1915, and his wife Rose, both down from London; and Christine, younger sister of his companion Ada Page, who was living with them at the time.

Francis was recovering from a third serious operation a couple of months earlier, which had followed more than a year in a nursing home in London. He was feeling much better, walking around the estate with Cundy every day of their visit.

After lunch he decided to show his guests over the Barham School, a building of interest to an architect and one of which he was rightly proud, but also somewhere he had not stepped inside for almost a decade because of his falling-out with David Bonvonni and his illness. But now he was feeling more like his old self again, and wanted to resume his old role as a school manager.

This was something to which David objected very strongly. On one occasion when Francis attempted to shelter in the porch of the school from a sudden downpour that caught him out in the open with neither coat nor umbrella, David told the infirm old man to leave, as he had no right to be there, his rank as Senior Life Manager notwithstanding.

So this time Francis asked his permission first. As it was school holidays, so nothing was going on apart from some redecorating, David gave his rather grudging consent and accompanied them for a while, being “very offensive, evidently trying to make a quarrel.”

Quarrel

Francis did not rise to his bait, replying “no one should quarrel during war time, let us live in peace.” David then left them to complete their tour, at the end of which Francis said “now I will show you in the committee room the portraits of my Uncle & his first wife, in whose memory this school was built, also the picture of his home in Kent.”

The Managers’ Room was part of the schoolmaster’s house but also accessible up a flight of stairs from the school — the buildings were not separate.

The Managers furnished and looked after it and had the right of access at all times, but David was permitted occasional use of it by the terms of his agreement with them in 1904.

Over time he had stretched the meaning of “occasionally” so far that he had come to treat the room as his own. On this occasion he and his small household were having their dinner there, which was by then their custom.

Francis, 75 and still quite frail, started walking up the steps to the door leading to the Managers’ Room and David, a vigorous 52, barred his way crudely.

“Man, where are your senses, you are going in the W.C.” Francis ignored him, bade his friends to follow him, and pushed the door further open.

David exploded “No, you can’t, this is my private house, you and your damned dog get out,” at which point he kicked the dog down the steps, “snatched the door away” from Francis and “pushed him so violently that he fell on his back, slammed the doors, pushed the bolts up, & locked up, he used so much force the handle was sent crashing to the ground.”

Francis fell backwards from the fifth step with his heels in the air and was only saved from cracking his head on a stone by the fact that he landed on Miss Page instead.

After checking that Francis was not badly hurt Henry Cundy and his wife rushed round to the front door of David’s house “to ask Bonv. the meaning of his conduct, told him he was a cad to have knocked down a old man (sic). Bonvonni then became aggressive & threatened to knock him down too, but Mrs Cundy was very frightened & begged her husband to come away but told Bonvn. he acted as a cad & a coward.”

This cooled matters, and when David saw Francis, “looking very white & shaky,” he said “oh, you may come in this way & sit down, if you like, I am sorry if you are hurt, I did not mean to hurt you.” But no one accepted his offer, Francis just sat on a ledge until he felt able, with assistance, to walk home, and then took to his bed, so feverish that they sent for Dr Morgan Owen to come from Fishguard.

This has all been taken from Henriette Miles’s full and fluent but obviously one-sided account, compiled from conversations with Francis, Christine Page, and the Cundys immediately after the event. It squares with their witness statements four days later and testimony in the trial of David Bonvonni on a charge of assault at the Petty Sessions in Fishguard soon after.

A Day in Court

Henry Cundy immediately contacted Francis’s local solicitor, and the magistrates issued a summons straight after Cundy and Miss Page went with him to make their statements. The trial followed ten days later and did not go well.

Henriette Miles thought part of the reason might have been that their solicitor was not fully briefed.

A better explanation is that Francis was, as usual, a hopeless witness in his own case, while David, a confident and experienced public speaker, put across a narrative of invention, denial, lying, explanation, and misdirection, which succeeded in so bamboozling the magistrates and their clerk that they dismissed the case.

Quite understandably, Francis could not remember anything after David hit him. He was also wholly unprepared for the defendant’s solicitor’s questions aiming to establish David’s alternative facts.

He did not answer any of them effectively: that he had been told by the other Managers not to interfere with the school; that he had been told by David that the entrance was private; that he had been told to leave; and that he had only been pushed, not hit.

David and his Daughter Lie Their Way Out of Trouble

David Bonvonni, in contrast, put in a bravura performance. His essential lie was his first, that “The School was taken over by the Pembrokeshire Education Authority in 1903. That is the only Authority over the School.”

This was a gross misrepresentation of the complex legal status of non-provided schools under the 1902 Act — it was what David and other Radicals and Nonconformists wanted to be the case — but it worked with the magistrates and their clerk, who either knew no better or agreed with him.

His purpose was to establish the idea that Francis had no right to enter the school or the Managers’ Room, and was thus a trespasser. “The house is entirely distinct from the School” — which was not the case — but “I have arranged with the Managers that they can hold their meetings in the room at the top of the steps.”

This was a complete reversal of the agreement he had signed with them a dozen years earlier, that the room was theirs but he could use it occasionally. It represented the facts on the ground that he had created over twelve years of continually pushing against the terms of the agreement, but not the words on the page.

So the Managers might use the room for their infrequent meetings, with his permission. But not Francis.

David claimed that he had had “considerable trouble with Capt. Barham on several occasions” — referring back to the old argument about the school bell in 1906 — and that the Reverend Rees, chair of the Managers, had stated “that Capt. Barham entering had no Authority.”

Iindeed, he had “received instructions [he did not say from whom, but the implication was the other Managers] to prohibit Capt. Barham entering the School” — something Francis had denied, but the result was just a conflict of claims that the magistrates could not resolve at the time, Reverend Rees not having been called as a witness.

David had “nodded approval” to Francis and his party looking round the school, but drew the line at their coming into his private quarters [the Managers’ Room], where his family were eating their dinner.

His reported words were very different from and far more numerous than those the Cundys and Miss Page remembered.

“Mr. Barham this entrance is private you have no right to come to my house … you are trespassing you have no right to come this way, come round to the front door.”

“The Capt. then replied ‘Oh, we are only going into the Managers room’.” David then repeated his previous words, and Francis said “I will go this way.”

So in this account David was polite but firm, Francis obstinate and unreasonable.

And then to the poor dog. David also remembered far more conversation about this than the Cundys and Miss Page did — just a couple of short, angry exclamations, and then a kick to the dog and a blow to old Francis.

In David’s telling, everything was explained — “I pointed to the dog and said ‘why do you bring this dog to my house also as it always fights with mine, my dog is there and should they meet [speaking in the conditional] there will be blood all over the carpets, take it out.’”

He did not kick the dog the length of the corridor, rather he “placed my foot under the breast of the dog and threw it down. There is a mat at the bottom” — presumably guaranteeing Fido a soft landing.

“The Capt. then pushed me aside with his right hand and said ‘don’t do that’. I said ‘Now Mr Barham get you out also.’” “I placed my hand under the Captain’s right shoulder and pushed him out of the door.

His feet seemed to slip. I did not hit him. I then locked the door and proceeded up stairs” — no violent slamming, no handle flying off.

As for Henry Cundy, he “came round to the front door running right onto the mat. He placed his fist near my face and said ‘I will send for the Letterston policeman to arrest you. You damn schoolmaster.”

David’s strategy of reversing facts came into play again — “Someone [Cundy was, he said, the only person there] pulled the door violently and I heard the knob falling off and I heard someone fall,” i.e. he transferred what he had done at the inside door to something Cundy had supposedly done at the front door.

Then “I told Cundy to clear off as he was trespassing” — “his wife was not there.” “Mr Cundy touched my face the second time.”

On the basis of this version, with Cundy as aggressor, he had summonsed Cundy for assault two days before his own trial, a bold move to undermine the standing of one of the key witnesses against him. There seems to be no record that any trial resulted, but the strategy worked.

David’s testimony ended with yet more improbable conversation that only he had heard. “Capt. Barham [who could not walk without somebody on each side of him, holding him up, according to his friends] came to the front door by himself and Miss Page about 2 yards behind.

He sat on the pillar and said ‘I hope nobody saw me tumbling down, I slipped my foot when you pushed me and fell backwards into the arms of Mr Cundy and Miss Page.’

I said I was sorry the occasion should have arisen and he said ‘I am sorry too, I ought to have come round to the front door, Mr Cundy told me so, I thought you had buried the hatchet’ and I said ‘And so I have it is you who have recussitated [sic]’ and the Capt. replied ‘it is all my fault, it’s all my fault, may we go into the Committee Room.’ I said certainly come this way.” But Miss Page declined the offer, and Francis did too.

David was bold, inventive, and fluent, and the brief cross examination did not touch or shift him.

He was supported by his daughter Nadine, his assistant teacher since his wife had left in 1912.

Nadine had remained in the dining [Managers’] room with a visiting relative, who was not called as a witness. She confirmed her father’s story, adding details that she could not have seen, even if they had happened.

“Capt. Barham resented [the expulsion of his dog] and pushed my father. My father put his right arm under the Captain’s right arm and pushed him out.” As for Cundy, “he was vicious and put his fist in my father’s face.”

At the end of it all, “Capt. Barham … walked by himself and expressed regret.” “My father did not hit Capt. Barham.” “I did not see the Capt. falling.” According to the other witnesses, this was because she was not somewhere she could see anything.

Perhaps a more alert advocate than Walter Williams could have taken David and Nadine apart, or the magistrates might have seen through him, like the barrister and judge he had run into at the Llanstinan right-of-way trial in 1910.

But on the day the magistrates and their clerk dealt with the matter differently. Faced with a conflict of evidence and also of claims about who exactly had legal rights of access to the Managers’ Room, they simply threw their hands up and decided “it was a question of title, and the Court, therefore, had no jurisdiction.”

A Second Attempt at Prosecution

Francis and, even more, Henriette Miles were stunned by the result. Could they appeal? Their solicitors’ advice that it was hopeless “arrived as a bomb.”

They then began to develop a Plan B: a civil suit against David for the pain and suffering he had caused Francis, and for costs (Dr. Owen’s medical bill).

The amount of their claim was trivial — it came to £27/1/-, including a nominal £1 for refusing Francis access to the room in question. But the aim was to win something, including an injunction restraining David from any repetition of his obstruction in the future.

This case occupied Francis’s solicitors and the barristers whose opinion they sought for most of the next two years. The paperwork it generated, even in the obviously incomplete form preserved in the archives, occupies 150 pages, many of them crammed with text. The cost was incalculable but probably significant.

Francis had to abandon his case, and write off his costs, in the summer of 1918. The rocks on which it foundered were the ones David and his solicitors had identified at the outset — uncertainty about the division of power between the parochial managers and the Local Education Authority; about how, if at all, the 1902 Education Act affected the operation of the founding Trust Deed; and about the meaning of the words in the 1904 agreement between David and his employers.

Unfinished Business

There are just three features of this long, tedious, expensive, confused, and unproductive legal process that are interesting.

The first is the barrister’s conclusion about what was essential to the successful prosecution of a case: “Get Cap. B’s [indecipherable abbreviation — attn, attention?] so that he will not drift & make light of the whole affair (as he is unfortunately too apt to do) — The gist of the whole biz is to get him to take a serious view & not give the show away as he did before.”

He evidently reached the same conclusion about some of what went wrong at the trial as I have, but as Francis’s courtroom performances since 1871 had amply demonstrated, the only way to prevent him from sabotaging his own case was to not call him to give evidence in the first place.

The second is what Henriette Miles and Francis said about why they were prepared to invest so much money and effort in the search for such an uncertain and limited outcome.

It was partly a matter of amour propre — as Francis explained, “I wish to avoid as much as possible unnecessary expenses, yet I feel I cannot let the schoolmaster have the laugh of me, I must revendicate my position as Manager of the Barham School.”

It was also, though, their hatred of David Bonvonni and desire to get rid of him somehow.

In this Henriette was even clearer than Francis, who had reservations about pressing the case, including the patriotic argument that “during War time & in view of the serious state the Country is in, this case is rather too trifling to occupy the time of the Court.”

Henriette had no similar doubts. “It is a lot of trouble yet unless steps are taken to put down the Schoolmaster, there will be no living at Trecwn.” “He has been a pest & a nuisance to everyone since he is come, & will be until dislodged, I fear this will be difficult.”

He was worse than a nuisance, he was also a threat: “It seems a monstrous thing that a notorious violent man like Bonvonni should be allowed to knock down a Manager of a school & the Court dismissing the matter.”

If Francis’s head had struck the stone rather than Christine Page, it could have been a case of manslaughter, not just assault. Whoever had title to the Manager’s Room, David had used excessive force to assert his rights.

And this was not the first time. He was not just a threat to his adult neighbours. Crucially, he was an everyday threat to the pupils he taught. “[E]verybody is afraid of him, he is quite unfit to have charge of children.”

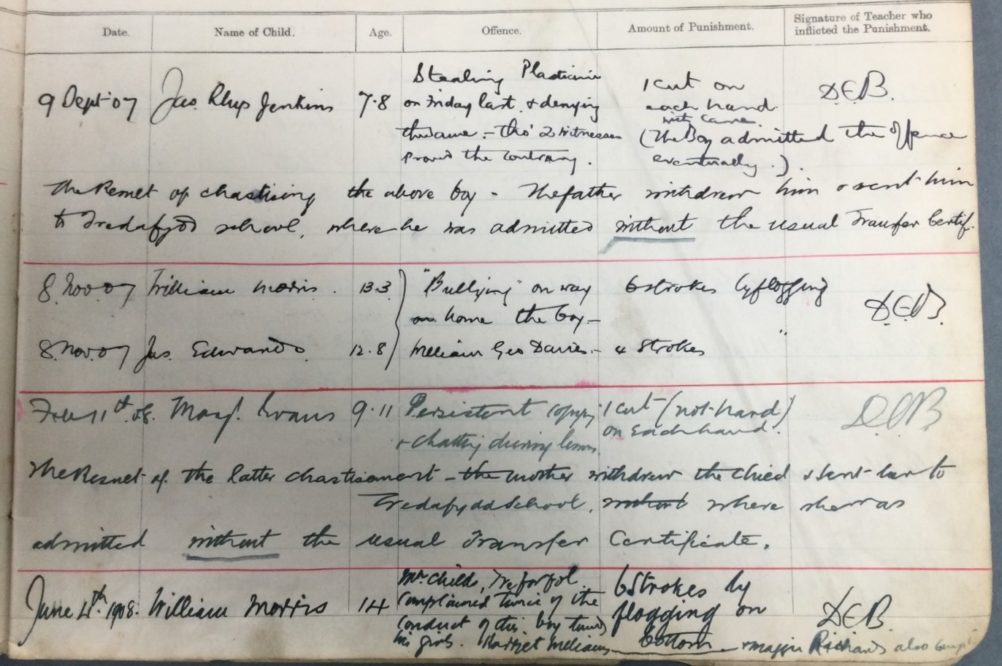

He was a bully. And for this she could have produced ample evidence. The school’s Punishment Book survives in the county archives. David did not spare either sex the rod and, if the rod was not enough for a boy, he was not averse to flogging.

Unsurprisingly some of his victims’ parents withdrew their children and sent them to other schools nearby. Shortly after his assault on Francis one of them even consulted a solicitor about David’s behaviour towards his son.

The third is the Reverend John Rees’s wise opinion about the whole affair: after “a further fracas between these foolish people” in March 1917, when both men behaved in “a very reprehensible and unseemly manner,” the best course would be to abandon the civil suit altogether.

David was no longer stopping Francis coming to meetings and using the room, and whatever happened in court he would still be around and “very obnoxious.”

He did not say this but others would reach the same obvious conclusion as Henriette Miles already had: the only real solution was for David to be driven out. But this would be neither quick nor easy. In the next episode we will find out how it was finally achieved.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.