House of Dogs: The Last Squires of Trecwn, Part 8 – The ejection of David Bonvonni

We continue our series exploring the history of a Pembrokeshire estate and its colourful family.

Howell Harris

On Saturday the 19th of July, 1919, the people of Trecwn were invited to a big party at the Mansion to celebrate “Joy Day” (the official ending of the Great War). “Tea was partaken of indoors in merry mood, Captain Barham and Miss Page making an ideal host and hostess [“gracious and charming”], the latter being assisted by a bevy of lady helpers.”

“Sports formed the great feature of the evening” — cycle races, athletics (running and jumping), other games (sack races, egg and spoon, even hat trimming), ladies’ tug of war (single v. married), bran-tub “dips,” and “free shies” at an effigy of “Kaiser Bill.” At the end of the evening the Kaiser was “exterminat[ed] in a huge bonfire,” and “the singing of the National Anthem brought a most happily spent day to a close.”

David Bonvonni organized the sports, his daughter and assistant teacher Nadine served as “general secretary” for the whole event, and both were singled out for special thanks in the official press report.

It might seem from this as if peace had broken out in Trecwn too, but in fact that was very far from the case. By September 1921 the Rev. Dr Herbert Workman, secretary of the Wesleyan Education Committee, was writing despairingly to Canon James Griffiths, the new vicar of Letterston and rector of Llanfair and chair of the local managers, about David’s “intense antagonism” towards Francis, and the “disquieting and unsatisfactory” situation at the school.

There were rumours about the teaching, a “flagrant instance of scandal” concerning the Bonvonni household, and a thorough inquiry was essential.

How had things reached this condition?

Star Head Teacher

Whatever problems there may have been in Francis and David’s personal relationship, David had always had a key source of strength: the high regard in which his and, until 1912, his wife’s running of the school had been held, by people who mattered if not necessarily by all of the parents of the children they taught and, in David’s case, caned and flogged.

In 1906, for example, at the same time as the two neighbours were falling out, the Bonvonnis were picking up fresh plaudits from His Majesty’s Inspector for the “very satisfactory state of affairs” resulting from their “sterling abilities.” They deserved “all praise.”

They received more the following year, for the school’s excellent Nature Studies exhibits at the Bath & Wells Show, the only ones from Pembrokeshire. David “deserved commendation upon having set such a good example to the rest of the county.”

He and Kate continued to extend and improve their teaching skills, going to summer courses in arts and crafts, and to innovate at the school.

They introduced practical subjects considered very suitable for a rural community (gardening, woodwork, housewifery, etc.) and evening classes through the winter for young people who had left school with only an elementary education (in Agriculture, Chemistry, English, Maths, and Domestic Science, leading towards City & Guilds qualifications).

Trecwn was unique in West Wales for this manual and vocational training approach, and singled out for congratulation by His Majesty’s Inspector for Manual Instruction accordingly.

It was not just other teaching professionals who held the Bonvonnis in high regard. So too did General Sir Edward and Lady Leach of Corston House, near Pembroke, relatives of the original benefactors. They gave presents to the children every Christmas (boxes of fruits etc., boots, dresses, and flannel shirting) and came to make inspection visits of their own. They were most impressed by the Bonvonnis’ work.

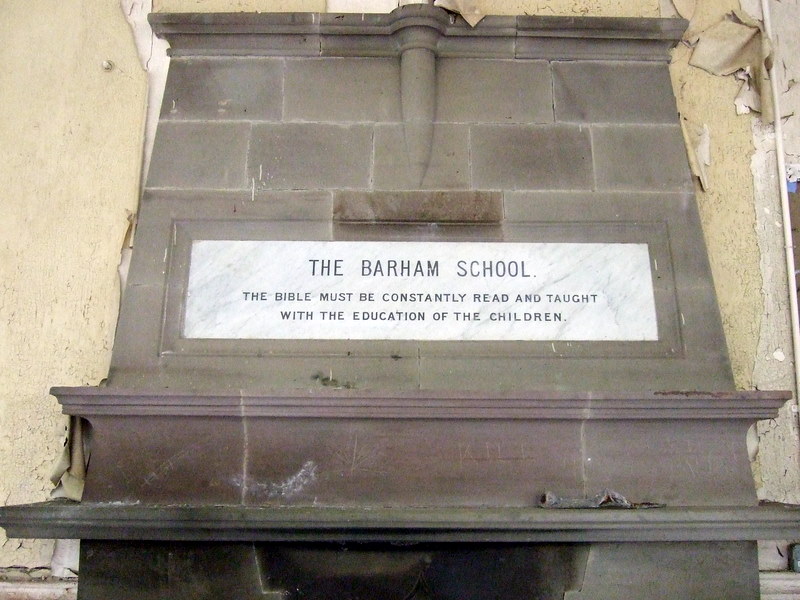

The Rev. Dr Workman was equally satisfied with the religious instruction the school was obliged to provide according to its foundation deeds, though his requirements did not seem to extend to testing the children’s understanding. The excellent “repetition of the various portions of the Holy Scriptures” and “singing” were enough to send him away content.

David Bonvonni was thus in a very strong position. In 1910 the Board of Managers (minus Francis) even proposed to include him among themselves, but as he was ineligible they let him nominate his own man instead.

Rustic Rebel

It was just as well that David seemed to be beyond criticism in terms of his job performance, because he was making himself increasingly vulnerable through his high local profile as a union and political activist.

He remained a vocal critic of any solution for the education question short of thorough secularisation, where any Liberal proposals, even compromises, were stymied by the Tory majority in the House of Lords. His opinions about religious oversight of schools like his were also deeply uncomplimentary.

He earned himself a nickname as the “Stormy Petrel” of the Pembrokeshire Teachers’ Association (the national union’s county branch), and his politics shifted well beyond Liberalism.

By the start of February 1908 he had become founding secretary of the Fishguard branch of the Independent Labour Party. By 1917 he was an executive committee member of the Labour Party branch, established the previous year.

He was also union president through the bitter Pembroke Dock teachers’ strike, having to fend off the “usual … bombast and calling the teachers Bolshevists and such like” from the Education Committee.

David was attaching a target to his own back. In 1920 Francis obliged him by firing straight at it and finding the weakest spot in his armour. The long campaign to get rid of him, or at least make him pay for his assault on Francis in 1916, had failed. This one would be a complete success.

Village Atheist

It had long seemed strange, given his strictly secularist views on the education question, and his complaints about religious interference in non-provided schools, that David should have been an, on the face of it, successful headmaster of exactly such a school as he wished to abolish.

Despite his good working relations with successive Rectors and Wesleyan inspectors, despite his high standing as a parish councillor and church organist, there must have been some questions and rumours about his personal religious convictions.

After all, by 1920 the parish was full of children and young adults who had been taught by him, some of them old enough by then to have children at the school themselves, and they all knew how he conducted his obligatory daily lessons from the Bible.

In April and July 1920, the Wesleyan inspector and local Rector made their regular visits to the school and found everything good, as usual.

But Francis determined to get to the bottom of those rumours and, though almost 80, he began once again to exercise his prerogatives as a school manager and to visit the school in person.

He made a thorough nuisance of himself. He checked the registers, signing himself “Senior and only life Manager,” sometimes bringing Ada Page along with him. He made himself familiar with the children.

He listened to the scripture teaching, interfered with discipline, even criticised a detail like the way St. David’s Day was celebrated in 1921, and sounded a bit disappointed on days when he could not find any fault.

And then he set in motion the process that would lead to David’s dismissal (or, rather like his own earlier experience, “involuntary retirement”) by the summer of 1922.

There were numerous grounds for concern, including David’s personal morality. His wife Kate had left the Barham in September 1912 to head her own school in a village at the eastern end of Francis’s estate, Henry’s Moat, though they still lived in the same house.

The Rev. Dr Workman, Wesleyan inspector, joked that “it might be as well to eliminate the first three chapters of Genesis” [Adam and Eve and the Serpent] from the curriculum, “considering the rumours that are current”.

But the files on David’s dismissal are disappointingly free of any juicy details, except for one cryptic note in pencil, after the date of Kate’s departure (1912) — “Mrs Cath Thomas Llanyrolchfa. Capt. B. told her to clear out. Boy — 6 yrs.”

What the files are full of is evidence that David was a militant atheist, and that this was the character of the Biblical teaching he provided when he did not have an adult audience to worry about.

This was the safest ground for the Trustees and Managers to stand on in firing a teacher at a non-provided school, because discipline for religious error was exempt from the requirement to have the local authority’s consent.

Francis set the ball rolling by encouraging the production of a parents’ petition of complaint, which all but two of them signed, some of them after Ada Page’s individual visits to their homes to persuade them.

“Our children are very backward with regard to Elementary and Especially in Religious Teaching. It is our wish that the Head Teacher should be changed and trust that this will recieve (sic) your immediate attention.”

Mystery letter

It is not clear to whom the petition was addressed — the Managers, the Trustees? But it was accompanied by a letter, not signed but probably from Canon Griffiths, which reads like an opening address to the resulting inquiry:

The names signed to the petition represent — I believe all of them — a lot of God-fearing men, who believe fully in the Bible and its teachings. And it is because they are jealous of this belief and are anxious that their children shall have every opportunity to imbibe the same truths that they cherish, we are here today.

I feel sorry, exceedingly sorry for the occasion that I am called upon to lay before you such deplorable facts.

Although I have heard rumours from time to time, still I paid no heed, but now after having been instructed 2 days ago, & gone into the case, I am simply amazed at what I have been told at first hand from young witnesses of the Atheistical teachings the Head teacher of this School has consistently for many many years endeavoured to instil into the minds of the pupils.

It was not that David did not know his Bible — he knew it better than most — but that “he has consistently almost daily used his best endeavours to induce the children under his care to disbelieve [it].” He was “unfit for the position he holds.”

“The serious consequences of his teaching during the past years are incalculable, & it is likewise difficult to estimate the results if he is allowed to continue to sow his evil seed.”

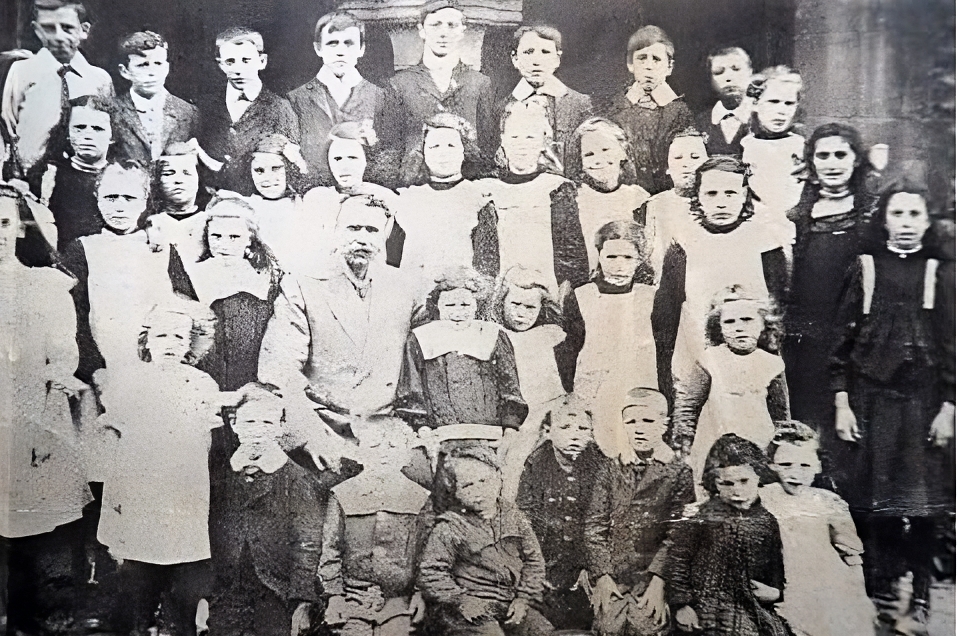

Religious instruction in the Barham School had always been a sensitive issue, even before David’s arrival, because of the inevitable friction when children of an overwhelmingly nonconformist community had to attend an Anglican school, albeit low-church and supervised by the Wesleyan Methodists. But having their children taught by a domineering, mocking village heathen was worse.

What did David actually teach in his morning Scripture classes? The testimony from at least seventeen current and former pupils, aged 9 to 31, and a couple of mothers speaking on their children’s behalf (they were isolated with chicken pox), was consistent and damning.

After he read the Bible verses of the day the children would repeat them, and then David would explain their meaning. They should not believe what they had just read. The Bible was just lies, or damn’ lies, or stories, some of them nice stories, but still lies. If people had ever believed it, it was only through ignorance. The Old Testament came in for particular scorn — a product of illiterates (i.e. the oral tradition).

There was no need to read the Bible. That wouldn’t get you to Heaven, because there was no Heaven (though sometimes, rather inconsistently, he told his class they would all go to Hell, which at other times he said didn’t exist either).

Sometimes he would not even bother to read the Bible himself, but put his feet up and read the paper instead — “The War is more interesting than the Bible.” This was an understandable point of view to adopt for an atheist whose two surviving sons were both in the Army, but not very wise from the headmaster of a church school speaking to a roomful of impressionable children with good memories.

His disrespect for the Bible was also physical — he would throw it on the floor, or across the school, sometimes at an unresponsive pupil. He would tear out pages from his own marked-up copy and put them on the fire, to emphasise his contempt for particular sections.

He comes across as a verbal as well as physical bully, telling a child who could not answer a question that he had better take some bread to Heaven with him, otherwise he would starve.

He mocked religion generally, and church- or chapel-going, as well as the Bible. He only went because he had to. He did not believe in God, he never would, and his pupils shouldn’t either. There was no God, and He had not created anything. Everything was the product of Nature, and Man himself was descended from monkeys (pictures of which he would show the children, to make his point).

Perhaps most explosively, when talking about the Children of Israel in bondage, David asked the children “Why didn’t God come down to help in the war against the Germans”? His answer: because he helped them. His words made no sense, except to drive home the point that he would not miss an opportunity to attack religious belief.

David was no gentler with the New Testament than with the Old. There was no Jesus Christ, and he did not give us anything. There was no Resurrection. Death was the end. When you went to the churchyard, you stayed in the cold earth. There were no miracles. He could turn water into wine just as well as Christ, and had done so many times (probably a joke about his domestic wine-making).

Nor did he confine his attacks to the Bible. Sometimes he would take the words of a hymn and treat it as a crude joke too, e.g. Hymn 341, about the Golden City to which children would go when they died, was one several pupils remembered. He told them that it meant Heaven would be a place where you played cricket and football and did not need to eat or go to the toilet.

Exit David

The outcome was unavoidable, and David’s KC, probably provided by his union, could do little to mitigate the consequences. He was offered the option of resignation without jeopardy to his 33 years of pensionable service and sensibly took it, though he would not be old enough to collect his pension until he turned 60 in 1924, and was now homeless as well as jobless.

He did not go far — he just moved to Fishguard, and may have turned his sideline as a semi-professional photographer into a full-time job. He also became an urban district councillor and chairman of the county Labour Party.

Now at last he was completely free to speak his mind as a radical opponent of the exploitation of the weak by the strong, which was, he said, the thread that ran through all human history from the very beginning.

“Long before there was any civilisation or capitalism the few strong and able were robbing and enslaving the many, and … evolution has merely improved and intensified the methods of exploitation.”

David still made occasional headlines, none of them positive. He was singled out by anxious English reactionaries as a dangerous “Red”, and prosecuted by the county RSPCA for “one of the most blatant and flagrant cases of wanton cruelty brought before the court” (he talked his way out of a conviction again).

The local papers also reported on his overblown but quotable rhetoric in dealing with parish-pump matters (increasing a rate assessment was “a downright insult” and “a cruel injustice” and another example of unfairness by the rich towards the poor), and on his underhand but characteristically self-righteous dealings with fellow councillors.

So David was still making trouble, but at least he was no longer doing it in Trecwn. No child at the Barham School was flogged or even caned in the five years after his departure. He died in April 1930.

Exit Henriette

Loyal readers, if there are any, may have noticed that Henriette Miles, Francis’s companion and advisor for almost forty years, and as hostile to David Bonvonni as he was himself, played no role in his final victorious campaign. This was because she had left Trecwn.

She remained in close contact by letter and probably visited, but she no longer managed his affairs, leaving Ada Page with all the responsibility for looking after the old man she called “the darling”.

The reason for Henriette’s departure was quite curious. Her husband Francis came home from the sea during the war, and worked with the Church Army on military bases in France, Egypt, and eventually England instead.

At one of the latter he met the children’s author and man of letters Robert Leighton, about the same age as he was, also doing war work.

They became friends and Leighton took him home to introduce him to his wife Marie, a romantic novelist. Mrs Leighton was still grieving after the death in Flanders at the end of 1915 of her son the poet Roland Leighton, fiancé of Vera Brittain and a key figure in the latter’s classic war memoir Testament of Youth.

Robert thought Marie needed to meet new people to take her out of herself; Francis was a big character and very diverting company.

Francis and Marie soon became much more than friends, and the Mileses and the Leightons formed a durable ménage à quatre, living in rural Sussex, then St John’s Wood in London, and finally moving out to the country together again.

Francis worked as a wireman on the railways; Henriette formed deep friendships with both Leightons and brought her excellent cooking and management skills to what had been a chaotic bohemian household.

The Leightons’ artist daughter Clare wrote about them quite fondly, as Llewellyn (sic) and Celeste Hughes, in her unreliable memoir of her mother, Tempestuous Petticoat. She described Henriette as short, plump, and ugly, but with still splendid breasts, bags of personality, and many strong opinions.

This unlikely turn of events meant that, after twenty years as a key figure in Trecwn, Henriette moved into an entirely different though not unfamiliar world — her father had been an author and journalist too, and she had spent more time since 1882 living in and around London than at Trecwn itself.

But she did not disappear completely, and will return in the next stages of this story, still capable of setting events in motion if only by writing letters from Hertfordshire.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.