House of Dogs: The Last Squires of Trecwn, Part 9: Old Age, Death, and Friendship

We continue our series exploring the history of a Pembrokeshire estate and its colourful family.

Howell Harris

After their final triumph over David Bonvonni, Francis’s last few years with Ada Page seem to have been quiet and contented.

There were no further well-publicised court cases involving him, and he even put the estate’s finances on a steady footing at last by the classic manoeuvres of the asset-rich but cash-poor landowner, selling off a swathe of outlying farms, fields, and houses to clear his mortgage.

In the summer of 1926, destined to be his last, the Western Mail painted an attractive portrait of him to celebrate his continuing the family tradition of munificence — he had just gifted a cottage, garden, and stables to the parish to serve as a caretaker’s house for the church.

‘Capt. Barham is … a most popular landlord. He is of a retiring disposition, and is much devoted to the ancient classics and modern languages. He prefers French to English, has a knowledge of several European languages, Hindustani, and a fair acquaintance with Welsh.

… Capt. Barham is very alert and active, and generally prefers running to walking. He thinks nothing of walking to Fishguard and back, a distance of ten miles. He is fond of his pipe, but never drinks anything stronger than tea or coffee.

He spends most of the year at his beautiful home at Trecwn, surrounded by his loyal tenants, but lives for a few months in the winter at his London house. He has never taken part in public work, but is held in general affection.‘

What had happened to him, apart from the airbrushing appropriate in a tribute to a generous benefactor? He had turned into a local ‘character’ and amiable, harmless eccentric. Perhaps the abandonment of alcohol, as well as the passage of time, had improved his disposition.

Despite the comments on his robust good health, in fact he did not have long to live.

He seemed to know it himself, wishing to add a tenth codicil to his 1912 will to leave £3,000 to Ada rather than just £100 a year, their Croydon house, and another property nearby. But he did not get around to it.

Francis Barham’s Two Deaths

In the middle of September he went swimming, as usual, in the sea at Newgale, an exposed and quite dangerous beach a dozen miles from home. He was carried too far from the shore by a tidal rip, cried out for help, and then sank.

Fortunately he was not alone. His friend Mark Hale, the headmaster of Dwrbach school in the next parish who had known Francis for his whole time as Squire and probably driven him to the beach, was walking along the shore with his daughter Mary, watching.

He stripped off most of his clothes and plunged into the sea almost immediately. He swam to where he had last seen Francis, dived seven feet down, and brought the big old man’s lifeless body to the surface.

With great difficulty he dragged him ashore, where he applied artificial respiration, and it worked.

Mark got a Royal Humane Society medal for his act, and little Mary an inscribed gold watch for helping, but Francis thought they deserved more.

So he promised Mark a farm in his will, and an immediate £100 so that he would not have to wait for Francis to die first.

But he did not consummate either of those good intentions, adding no codicil and telling Mark when he called for his cheque that his bank account was overdrawn. There would be no £100 and no farm.

Did Francis ever fully recover? Henriette Miles was so concerned about the lasting effects of the physical shock that she wrote to insist that Ada Page must get Dr Gwilym Lewis to give him a thorough check in mid-October.

Lewis was reassuring: he examined his “heart, liver and lights and he was good for another twenty years.” This turned out to be over-optimistic.

At midnight on the 7th December Francis began to experience “heart trouble,” and Ada was with him all night until he died at 9 the following morning, after great agony with pain between the shoulders.

Strangely, she did not phone for a doctor, and early reports about his death were inconsistent with this account.

The certificate from the Humane Society commemorating Francis’s lucky escape from a watery grave arrived at a grief-struck Trecwn in Wednesday’s post, too late to matter.

That same day she told Henriette “my darling C.B. [Captain Barham] (The Wolf) passed away in my arms this morning suddenly at 9 a.m.,” and three days later Canon Griffiths, Rector of Llanfair, told Francis’s eldest daughter Winifred that “he died rather suddenly in the morning … He was seemingly in his usual health but somewhat feeble the evening before.”

There was no inquest, and questioning at the later trial of one of his executors on grounds of perjury in completing the cremation form did little to explain Ada’s omission or resolve the inconsistencies in these accounts.

Funeral Rites

On Thursday 9th one of Francis’s executors, the Rev. David Jenkyn Evans, 75, formerly Curate of Llanfair and Vicar of Pontfaen and Morvil, 6 miles away at the eastern end of the Barham estate, rushed back from his retirement home in Clevedon in response to Ada’s call.

They had been friends for sixteen years, and he had worked alongside Francis and Canon Griffiths on the Bonvonni dismissal four years earlier.

Another old friend and ex-executor, Sir Thomas Cato Worsfold, Deputy Lieutenant of Somerset and Francis’s London solicitor since the 1896 divorce, came with him to help, including registering the death.

Doctor Lewis recorded the cause as “senile decay” and cardiac failure, with “nothing unusual or suspicious,” so there was no need for a post-mortem, and he signed the death certificate.

Francis had long had an overwhelming fear of being buried alive, and had told his friends for years about his desire to be cremated, including this in his 1912 will and repeating it in the ninth codicil in 1919.

Henriette Miles mentioned this when she wrote to his son Cyril on Thursday the 9th; she even thought she knew where the cremation would take place — Golders Green or Woking — and that his body would be leaving Trecwn the following day.

She knew this because Ada wired her at noon on Thursday “Do not come all leave for London tomorrow with the darling will write if possible if arrangements alter.” But they did change, and she did not write again, and this was a Big Mistake.

At 10 o’clock the next morning, Friday 10th, Sir Cato rang up the recently opened crematorium at Pontypridd, the nearest facility and the only one in Wales, to see if Francis could be cremated there, and ask for the requisite forms.

But there was no way they could be posted to Trecwn, arrive in time to be completed, and then be brought back with the body the following day before the crematorium closed (11 a.m.).

So the crematorium director pulled out all the stops to make it happen. Sir Cato paid for the forms to be hand-delivered, put on a train for Cardiff at 1.35 and then passed to a train for Fishguard, arriving about 7 p.m.; and the director also extended the hours of Saturday opening to 1 p.m., to accommodate him.

Why such special treatment? It probably helped that Sir Cato was a baronet, former Tory MP, and toff. But why the change of plans, and great haste? The only explanation later offered was that Sir Cato had to be back in Somerset before Sunday, for no reason ever stated.

But there is another plausible motive. If they thought that Francis’s children, particularly Cyril, would make any difficulties and attempt to obstruct or delay the cremation their father had desired, there was every reason for Ada and the executors not to let them know, and to rush ahead with it as soon as possible, before the family could find out.

Given Cyril’s later conduct and statements — for example, that the old man’s body could have kept perfectly well for another ten days, giving plenty of time for an investigation into the circumstances of the death, as his children desired — it would have been a sensible precaution.

The only certain way to keep Francis out of their hands was to deliver him to the fiery end he desired as quickly as possible.

In any event, the forms arrived on Friday evening and were quickly completed. The Cremation Act of 1902 required answers to two key questions:

Had the next-of-kin been informed? Ada told Sir Cato and Jenkyn Evans — or at least she later said that she told them, and they confirmed her story — that she had been in touch with those whose addresses she knew. But she did not add her later caveat that she did not know any of them, which would have been even more directly untrue.

She had written to Cyril earlier that year.

Had a doctor been in attendance? If so, then just one signature (Dr. Lewis’s) was needed; if not, two. Jenkyn Evans, presumably with Sir Cato’s professional guidance, answered very carefully in a way suggesting that Dr Lewis had attended, though in fact he had not, as he had not been called.

Because Sir Cato was legally qualified, the Rev. Evans was able to swear before him that the questions on the cremation form had all been properly answered, saving yet more time by not needing to find a Commissioner for Oaths deep in rural North Pembrokeshire on a Friday evening in mid-December.

Francis was cremated on Saturday 11th at 1 p.m. Ada and the executors took the coffin with them on their drive back to Somerset, dropping it off at Pontypridd on the way.

Francis had set at least one record, though with rather than in his life: the fastest cremation in the west. There was usually three days between submission of the completed forms and the final act, rather than a few minutes.

The only one of his children who found out about it for themselves and was able to attend was Winifred, a nurse living in Cardiff.

Francis Barham’s ashes were placed into “an indestructible weather-proof casket of solid gunmetal” inscribed simply with his name, the date of his death, and his age, brought back to Trecwn the following Sunday, and buried by the wall of Llanfair church, next to his relations and ancestors.

The service was carried out by his old friend Canon Griffiths. A long, difficult (for himself and others), and achievement-free life had come to an end. An enormous legal argument was about to begin.

De Mortuis Nihil Nisi Bonum

After his death friends and acquaintances gathered together and shared their recollections of him, which complement the Western Mail’s premature eulogy.

There was plenty of agreement about his eccentricity. His GP thought him “a funny old chap,” owning a magnificent mansion and choosing to live in its poorest room. George Bennett, a Trecwn gardener, remembered one of his ways of taking exercise or recreation: going outside to burn brushwood at 2 or 3 o’clock in the morning, variously described as stripped to the waist, or just with his coat and waistcoat removed — either way, odd behaviour in an elderly gentleman.

He did not even wear a hat in an age when everybody did, because he had heard of (or seen?) a man killed by a motor-car while chasing his hat, so resolved never to wear one again.

Dr. Workman, Principal of the Westminster Training College for Wesleyan Ministers and religious education inspector for the Barham School, noted that Francis was a man for getting “bees in his bonnet” like this, or, he might have added, his fear of being buried alive.

And once they were there, they were likely to become fixed — notably his dislike of Anglo-Catholicism and Roman Catholicism, and his loathing for David Bonvonni.

But beyond the eccentricities, there was much about him to cherish and respect. He impressed his solicitor, Frederick Morgan, as “a brilliant and delightful man,” “interesting and intelligent” and “capable of transacting any kind of business.”

John George, his Fishguard dentist, found Francis “a highly intellectual man. He was the only one who ever made him … feel ignorant. (Laughter.)”

Howard Jones, Bonvonni’s successor as headmaster at the Barham School in 1923, “often used to play chess with [Francis] who was the best chess-player he had ever met.” He could also be a sparkling, stimulating conversationalist.

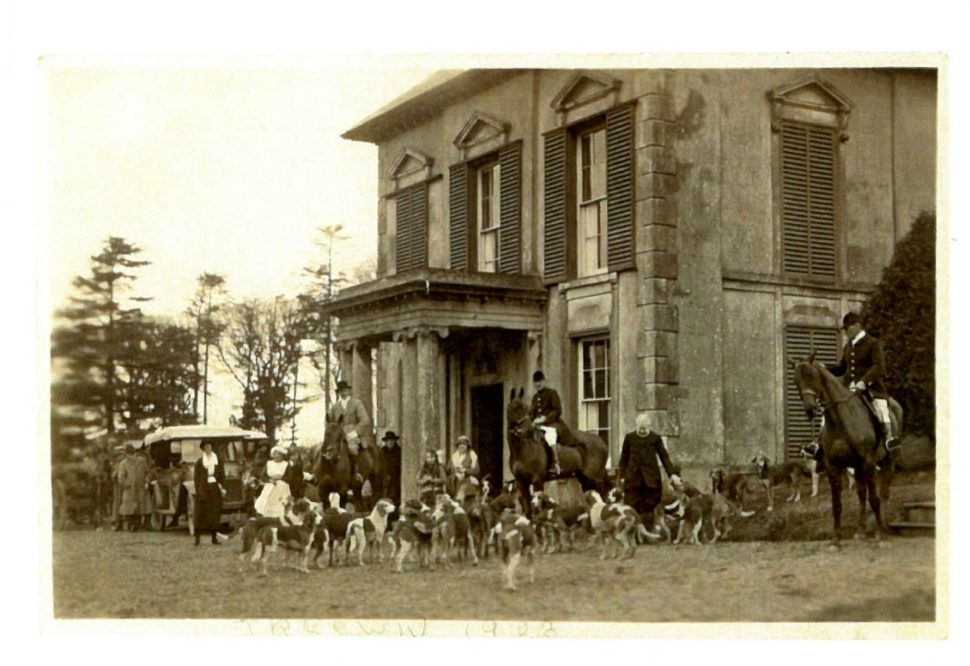

David Harris, a cattle dealer, found him excellent company — “he always talked intelligently, especially on foreign affairs. He was full of life and very jovial, and they often followed the otter hounds and fox hounds together.”

Strangely, this devotee of the Game Laws did not have a gun and did not shoot, but he went on shoots with neighbours and friends, where he was a complete liability: “His company had rather a disturbing effect, as he would begin to ‘jabber’ when a bird rose, and this would put them off their shot.”

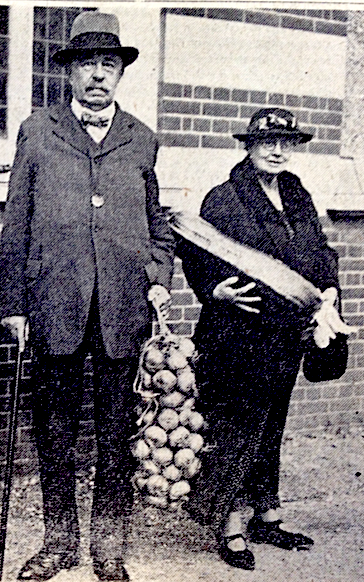

Archibald Hodges, clerk to Fishguard Council and Francis’s land agent, thought him “a very distinguished figure,” with a well-stocked mind that he used his ample leisure to resupply.

He “would sometimes stay in bed till the afternoon, often reading French newspapers. He was a prolific reader.”

Francis was quite an exotic in rural north Pembrokeshire, but equally happy talking about “district council affairs and such-like” with his cattle dealer friend and about his “great knowledge and love of the theatre, which he was particularly fond of discussing” with Canon Griffiths.

He was an obviously educated man, who “used to interlard his conversation with quotations from Scripture, poetry, and the classics, but they were always relevant.” His range of languages even came to include Welsh.

Francis began to learn the native tongue of most of his neighbours in 1918, from an elementary school teacher who gave this 77 year-old “The First Baby’s Welsh Book” to help his progress.

He became reasonably fluent — “I do not say he was quite correct but he got the meaning.” He wrote to her half in English and half in Welsh, just like he had to his children, where he moved seamlessly between English and French.

But being a considerable linguist did not necessarily mean that he was a great communicator. Hodges noted that he “spoke English very quickly, and that would account for some misunderstanding among some of the Welsh people.”

His solicitor’s managing clerk remembered that “sometimes one word stumbled over the other.”

How much of his difficulty with people was caused by his simple inability to make himself understood and, as so much of his courtroom testimony demonstrated, his disinclination to think before he spoke?

So he was not perfect, and some of his behaviour strayed beyond charming eccentricity into being quite annoying. David Harris noted that “He had an absolute mind of his own.” He did whatever he wanted and would not listen.

He also still had the quick, hair-trigger temper he had displayed for decades, exploding in outbursts of unexpected anger at trivial provocations — for example when English friends mis-spelled his address as Trecwm — but in old age just with words, not physical violence.

He was also very self-centred. His surgeon Sir Alfred Fripp was irritated by his tendency to turn up without an appointment and wander off if he was not seen very quickly. (Treating his solicitors the same way may be an explanation for his failure to write the planned last codicils to his will, leaving Ada Page more money and Mark Hale the promised farm.)

Sir Alfred also found his conversation less sparkling than his Pembrokeshire friends thought — “He always wanted to tell the story of his life, which was rather boring.” I hope some readers disagree.

His friend Canon Griffiths summed him up: clearly no angel, but he had “fewer failings than hundreds of people.” Unfortunately, among those most inclined to disagree with that conclusion were his own children, notably his son Cyril, who set about overturning his father’s settled intent to cut them all out of his will.

In the process he showed himself to be a much worse, more damaged and damaging person even than his father had been in his prime.

You can find the rest of the episodes here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.