House of Dogs: The Last Squires of Trecwn, Part five – Francis acquires a new surname and an estate of his own

We continue our series exploring the history of a Pembrokeshire estate and its colourful family.

Howell Harris

Francis’s mother finally died in 1899, and he gained possession of the estate at the age of 58, changing his surname to Barham the following year. The mansion was still let to tenants until 1901, so it took him a while to move in himself.

But he immediately made his presence felt, falling out with the local land agent, James Thomas, who had looked after Trecwn for his mother and uncle for forty years, ending his contract, and disputing his final bill. So he made the first of his many appearances before the Crown Court in his new county in October 1903, where he lost on every point and had to pay up.

This first lawsuit from his Pembrokeshire years illustrated why the apparently genial old gent in the portrait below could be such a difficult (and self-defeating) man: quick and angry decisions, self-righteousness, blindness to the defects in his own case, stubbornness, sometimes vindictiveness, a touch of meanness, and a streak of paranoia.

He accused Thomas, in court, of a “confidence trick,” which the judge summarised quite accurately as doing what he had been asked to do, presenting a very reasonable bill for his services, and expecting to get paid.

The Hyena

Part of the problem in Francis’s dealings with Thomas was that they had been done through his local representative, Henriette St. Hilaire (Camille Bornier), whom he called either “Minouche” (Pussy or Kitten) or “The Hyena,” perhaps because of her laugh. Her official status was as “a kind of adopted French niece” — the way she was described in the 1911 Census.

She looked after affairs in Trecwn while he was preoccupied with “pressing engagements in London.” But he did not seem to consider himself bound by, or responsible for, anything she had arranged on his behalf.

Camille/Henriette was the first and most important of his younger female companions to figure in the records of Francis’s tenure of Trecwn. He could not remarry until his estranged wife Mary died, but this did not necessarily mean that he was alone.

Henriette popped up in the local papers over the next few years as a member of a gentleman’s household rather than as any sort of servant — going out with the otter hounds, sending a wreath to a gentlewoman’s funeral jointly with Francis, being listed among the ladies and gentlemen at the Letterston St. David’s Day Concert.

Living at Trecwn

Francis did not maintain a large household at Trecwn, a mansion with 29 habitable rooms (i.e. excluding sculleries, lobbies, landings, closets, bathrooms, and offices). His tenant in 1901 had seven family members and six resident domestic staff. But at the 1911 Census, Francis only had one family member, Henriette, and three live-in staff (a groom, a parlour maid, and a cook), plus other outside staff in their own houses (gardeners, the estate foreman, the gamekeeper).

Other staff must have been drawn from the village and surrounding farms.

He did not live lavishly, and it is clear that his financial troubles were not over when he acquired the estate. He continued renegotiating his mortgages several times between 1901 and 1908 (some of his “pressing engagements,” perhaps), as well as making piecemeal sales of outlying farms.

But there was enough money to modernise the house and make Trecwn more convenient — installing electricity and telephone, acquiring a motor car and chauffeur.

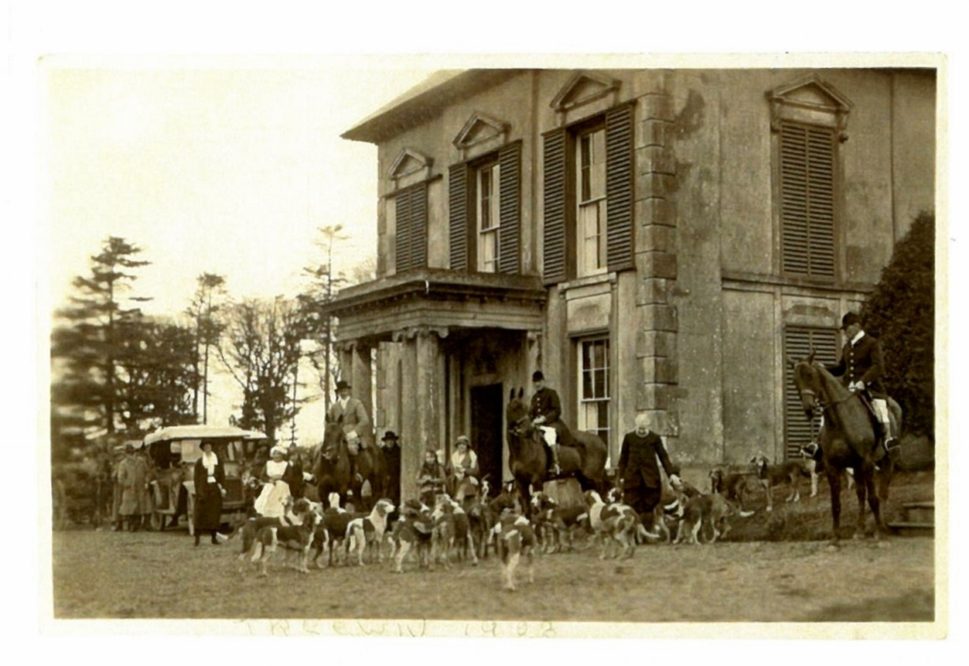

So his life, though not unconstrained, was more comfortable than it had been for decades. He could afford to be sociable, notably with other local sporting gentlemen who enjoyed his hospitality for hunting, shooting, and fishing, but also with some of his Welsh neighbours.

Family Problems

His improving prosperity had one major cost for him. It helped persuade his wife Mary, by then living in Hove, Sussex, to take him back to the High Court in 1907 in pursuit of the £1,121 (£550,000) that, she alleged, he had underpaid her since her 1888 alimony order against him through reducing what he paid whenever another of his children turned 16.

Her lawyers had already been badgering him for an increase from 1901 onwards.

She failed, and for once he did not have to pay her costs as well as his own, but her action had the effect of reminding the newspaper reading public of his new home county about the sad and discreditable story of their marriage.

Francis used some of his wealth to attempt to manage the lives of his now grown-up children, but with very limited success.

Cyril had complied with his demand that he must go to Oxford, but he cannot have been a natural student.

It took him four years, 1895-1899, to obtain a Fourth Class in Jurisprudence at St. John’s College, but with no Bachelor of Civil Law degree to cap it.

He did not even make any inquiries of the Agricultural College at Cirencester, let alone apply or get a Diploma, so he had failed two of Francis’s three conditions.

Disappointed

Francis, disappointed, disinherited him again. Their relationship, mostly by letter and in French, swung wildly from Francis “assailing his son with bitter epithets and sardonic irony” towards temporary reconciliation, and back again, for the rest of his life.

If he had known everything that Cyril got up to in the 1900s he would have been yet more certain that he had done the right thing, but for that you will have to wait until Episode 10.

His daughters were even less manageable.

Francis had inherited a rigid anti-Romanism from his own father, a prejudice he extended to include Anglo-Catholics and sustained until the end of his life. This was the explanation for the strange condition he set for Rita when he made the little girl his heir, aged 6, in 1888: she had to remain a Protestant, or she would be disinherited too.

They all disappointed him.

Winifred turned 21 in 1896, Sybil in 1897, and Rita in 1903. Winifred joined the staff of an Anglo-Catholic girls’ boarding school, run by a teaching order, in Oxford. She went on to become a nun herself but left after a few years.

She returned to live with her mother, by then in Sussex, in her early 30s, and during the Great War became a nurse. She kept trying to repair relations with her father until almost the end of his life, but he was durably embittered towards her, for her loyalty to her mother as well as her religion.

Sybil was even more rebellious. She rejected his offer to pay for her to go to Girton in Cambridge and became a nun instead, but unlike Winifred her vows were permanent.

Eventually she left the country for good and ended up in a convent in New York.

So she became quite dead to him, and will not figure at all in the rest of this story.

As for Rita, she did not even take his new name when he became a Barham, as Cyril and Winifred did, remaining a Robins, perhaps out of loyalty to her mother, as long as she lived.

She also rejected his entreaties to her in the late 1900s that she should live with him at Trecwn and the accompanying offer that, if she married, her son could inherit. She came but she did not stay.

So in 1912, aged 30, she too joined her siblings, disinherited and spurned.

Image courtesy of her grandchildren.

She lived with her mother in Edinburgh while she attended university, and eventually, after Mary’s death in the mid-teens, became a teacher in a Catholic prep school near Liverpool.

Francis turned his back on them all, and left his estate to the young children of his niece Clare Squire instead.

Gertrude was 8, Adrian 6, and Lawrence just 2, but they too would have to satisfy his demands if they wished to get their hands on Trecwn in due course. They must change their surname to Barham and abandon their Catholicism. Francis was nothing if not consistent in his prejudices.

Francis Barham, Serial Litigant

Francis was not a full-time resident – he maintained his house in Croydon for the winters, was an avid theatre-goer when he was in town, and continued to travel to France with Henriette for vacations.

But he was around for enough of the year to get into plenty of arguments, and to add to the bad and quite costly publicity that seemed to pursue him throughout much of his life.

Misunderstandings, fallings-out, and the resulting legal cases, often over trivial sums of money, littered Francis’s quarter-century as a Pembrokeshire squire.

Unusually, he did not participate in the public life of the county at all. A landowner of his significance (c. 4,500 acres at the estate’s peak) could expect, and would be expected, to become a rural district and county councillor and magistrate more or less as a matter of right, or duty.

So his court appearances provide most of the evidence about his Pembrokeshire years that made it into the local newspapers, and his solicitors’ records of those cases are the richest and most abundant material about him that the county archives hold.

Francis’s lawsuits were never just about the money, they were also about his insistence on being right. In 1906, for example, a local carpenter sued him for non-payment of a £2/2/1½d bill for work at the mansion.

Francis refused on the grounds that one of the men doing the work was an apprentice, and that the work should only have taken three days, not nine, anyway.

The judge dismissed his arguments and ruled against him, with costs.

The following year the same thing happened with a different builder for work on one of Francis’s properties, Llanstinan Stores, but for basically the same reason: Francis was a distrustful, pernickety, and tight-fisted customer.

He was no better as an employer, with the result that workers came and went — carpenters, for example, “were like new moons, always changing.”

In 1909 young John Bogg, son of Fred Bogg, formerly his head gamekeeper, whose words those were, sued Francis for non-payment of £6/4/- wages due to him for his time as an apprentice carpenter on the estate.

Francis had not just agreed to pay him far less than he should (3/6 a week bringing his own lunch, rather than a fair 5/- with lunch provided), he had then not paid him anything at all, though his housekeeper had given John £1.

Francis’s defence was to deny that there had ever been any agreement between them, to state that the £1 was just a present, and to apologise that he could not remember any of the details because he had been ill.

That at least was true: he had had two operations at Guy’s Hospital under the knife of Sir Alfred Fripp, the distinguished surgeon to royalty and other members of the élite, from which he was still recovering at the time of the trial and only walking with difficulty.

He “tried to make my mind a blank when I went in [to hospital], and it appears I have succeeded pretty well. (Laughter).”

The courtroom may have been amused, but the judge wasn’t: he awarded young John the full sum.

This case was also interesting because it illustrated the way in which Francis ran his estate, with responsibility divided in no clear way between himself, his agent, and the woman who really ran things, Mrs Henriette Miles, who had actually paid John Bogg his £1 non-wages.

Mrs Miles

Mrs Miles was the new incarnation of Camille Bornier since her marriage (under her original name) in 1904.

Her husband was Francis Henri Miles, a couple of years younger than she was, and son of the old Rector of Llanstinan.

Frank Miles was recorded at the 1911 Census as still domiciled with his older married brother, an author, and not present because he was a merchant mariner at sea.

His normal absence and their lack of a marital home would explain why Henriette continued to live at Trecwn, and remained an important figure in the household and around the estate.

Theirs may not have been a marriage of convenience, but it was certainly convenient for Francis that he could still depend on her.

In 1907 advertisements in the papers for domestic staff gave her as the person to contact, and she was soon managing all of Francis’s affairs.

She made purchases at sales, let farms, collected rents, represented him in a compensation claim, oversaw construction projects including rebuilding the parsonage at a cost of £1,900, and even drafted the will in which he disinherited all four of the children whose governess she had been.

She also still travelled with him — to Croydon for the winters, to Paris in 1914.

She had no formal role — she was not a working housekeeper. The way she described matters herself was simply that Trecwn was her home. “I did it to amuse myself. I like work, and wanted to do work.”

Another explanation for her growing importance may have been Francis’s prolonged ill-health between 1908 and 1916, which resulted in not just the two operations in 1909-1910 but a year in a nursing home and then another operation in 1916.

Perhaps Henriette simply had to run the estate because, much of the time, he could not.

According to later testimony, even before he fell physically ill he was so peculiar in his behaviour and disordered in his thoughts that he could not manage his own affairs and relied on her for everything.

And yet, against all of the evidence, Francis still insisted on denying that she had any proper authority, in order to try to get off paying (six years late!) the bill of a local auctioneer she had commissioned to do an inventory of the mansion in 1912, when he was considering letting it furnished again.

All of this to ‘welsh’ on a £10/15/- debt for what the judge described as “a tremendous amount of work” which had resulted in the production of a typewritten inventory, pages long, which it would be fascinating to see, had it survived.

The auctioneer’s lawyer tried to pin down what Henriette’s role had been: “I think we may describe Mrs. Miles as a general manageress? [Francis] I hope you won’t describe her at all.”

Henriette was no more responsive or credible as a witness than Francis was himself. The auctioneer “had a very good time of it” while compiling the inventory.

“He came about 10 o’clock, and at noon she gave him a very good dinner. [Prosecuting solicitor] He was very well entertained? (Laughter). [Henriette] He didn’t have a bad time of it at all.”

She thought it was “abominable to bring an action of this kind in war time,” because it was “a bogus claim.”

She did not help herself, or Francis. The main reason the poor auctioneer had been slow in presenting his bill was that he had volunteered in 1914 and spent the rest of the war in arms. The judge lost his patience with both of them, and Francis lost the case.

The Mule

Henriette was not the only one of his younger women companions to give the Pembrokeshire reading public as well as the trial audience at one of Francis’s court appearances cause for amusement.

There was also the central character in a 1908 case that the Pembrokeshire Herald described as a “Screaming … Farce.”

It was a complicated matter involving the breakdown of his relationship with Miss Lucia Mary Mooning, b. 1875, whose official role was as his housekeeper, but who may also have been Henriette’s successor in another capacity after her marriage to Frank Miles.

Francis was on “very friendly terms with” Lucia and gave her the pet name “The Mule,” perhaps because of her stubbornness; hers for him was “The Grizzly Wolf,” though the judge suggested that “Grizzly Bear” would be better (see the picture at the start of this episode), provoking laughter in court.

An alternative might have been “Old Goat”.

He was very generous to her, for example opening an account with a jeweller’s in Croydon where she had free rein to order jewellery for herself (some of which she wore at the trial, where she testified).

In 1905 he offered to pay her £100 down and £50 a year.

He later raised his price to £250 per year — significantly more than he was paying his estranged wife.

But she abandoned him after three years, leaving his employment to marry Walter Bourdon, the recently widowed elderly managing director of a small cycle and motor company in Kent, instead.

Francis went down to Somerset to intercede with her family (at their invitation), and raised his offer to £1,000. She still refused, and the marriage went ahead.

The case was about two rather confused payments of ten guineas that he made to Lucia after she had left, one of which she refused and returned, the other not.

In this case Francis won his ten guineas back but no costs, so once again he had a lawyer’s bill to cover that was probably larger than the sum at issue, as well as the damage to his reputation from having his unorthodox domestic arrangements exposed for public amusement.

His testimony on his own behalf was unconvincing but quotable, as usual — “Oh! dear no! I offered ten guineas for Miss Mooning, but I would not have offered ten cents for Mrs Bourdon. (Great laughter).”

The defence solicitor “said he felt sure that His Honour, as a man of the world, would take the proper view. The relationship between the parties were (sic) of a nature about which they could form their own conclusions,” which they probably did.

The Panther

After the departure of Lucia Francis was also disappointed in his hopes that Rita, his youngest daughter and heir, would take her place, at least in some respects.

So in about 1911, when he turned 70, Francis acquired his last young female companion, Henrietta Ada (Noel Douglas) Page, more than 40 years younger than he was.

Ada would share the task of looking after him with Henriette Miles through his years of illness until 1916 and then of renewed vigour afterwards.

She was his partner and fierce protector (his nickname for her was “The Panther”; she called him CB or “The Wolf”) for the next fifteen years.

Ada, as she was usually known, or Noel to close friends like Henriette, was born in Whitchurch, Cardiff in 1882, the daughter of a Taff Vale Railway Company executive, so she was the same age as Rita.

By 1911 she was 28 and still living at home in Caerphilly with her parents and two other single adult sisters, 22 and 34, who also had no occupation.

Her father had been forced to retire on grounds of ill health (he was gripped by delusions that he was the heir to a defunct title and an immense fortune), and her mother was the household’s only breadwinner. So a situation as companion to an eccentric and ailing elderly man in a country mansion miles from her home must have seemed comparatively attractive.

Francis proposed marriage to her in 1917, after his wife Mary had died; but she declined on account of his age. Still, she did not leave him, and she would be with him until he died in her arms nine years later.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.