House of Dogs: The Last Squires of Trecwn, part two.

We continue our series exploring the history of a Pembrokeshire estate and its family.

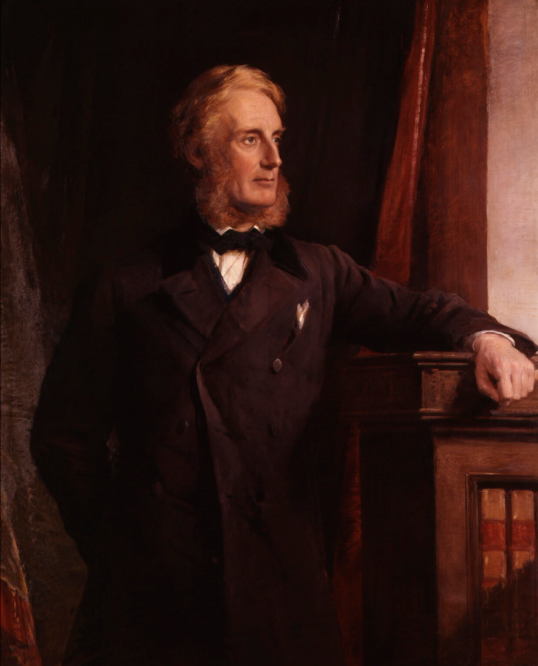

Francis William Robins: His Brilliant Military Career…Goes Bung

Howell Harris

Francis Robins was born in St. John’s Wood in London in 1841 and mostly brought up in the capital and Kent as his father moved from parish to parish.

After completing his schooling at Eton he joined the 60th Regiment of Foot (the King’s Royal Rifle Corps) as an Ensign (by purchase) in 1859, and made his career with them for the next dozen years.

The 60th Rifles was an elite light infantry regiment whose essential purpose by the 1860s was colonial policing. Part of his battalion, the Second, participated in the mopping-up after the Indian Mutiny in 1858-9.

The rest, presumably including Francis, joined them in 1860 from Cape Colony, where they had been based since 1851, in order to participate in the Anglo-French punitive expedition to Beijing that ended with the burning of the Summer Palace and an orgy of looting.

Promotion

They returned from China in spring 1862 for a quiet period of garrison duties in southern England — which was when Francis purchased his promotion to Lieutenant — interrupted by a year on active service in Ireland 1866-67 in anticipation of a Fenian rebellion.

Then they left for India again, the first British troops to travel via the new route involving a railway journey from Alexandria to Suez rather than the traditional voyage around the Cape.

They settled into a decade of garrison duties in Seetapore, Benares, Peshawar, Nowshera, Rawalpindi, and Meerut, and then saw all the action they could ever have hoped for in the Second Afghan War, 1878-80.

But Francis did not make it past Peshawar, gateway to the North-West Frontier, and he was not with them every step of the way there either.

In January 1868 he married Mary Agnes Cook (b. ?1848), a member of a locally prominent family from London, Ontario, in Montreal, where he was stationed. He was probably on detached duties with the First Battalion, which was guarding against Fenian incursions across the American border.

Francis was “very highly educated, a classical scholar with Latin at his finger’s ends; a fine linguist, acquainted with many languages,” including Italian, Hindustani (Hindi and/or Urdu), and most of all French.

In 1870, he became the Second Battalion’s official Interpreter and was with it at Peshawar. In 1868 he may have been rendering a similar service to the First.

His life might have turned out differently if he had stayed with them to participate in putting down the Red River Rebellion of the Métis in what is now Manitoba in 1869. But instead he and Mary voyaged to India to rejoin his unit, moving with them from Calcutta to Benares.

He passed the Military Board with distinction, was among the Regiment’s most senior Lieutenants, and could confidently anticipate promotion to a Captaincy in 1871.

But there was a price to be paid for pursuing his career. He and Mary suffered the tragedy of the death of their first child, whom they had named Cecil Humphrey Sackville after Francis’s great-uncle Sackville Tufton, late Earl of Thanet.

The Earldom was defunct but Francis, like his uncle Charles, may have had some hope of succeeding. Cecil was born, baptised, and died at Benares while they were stationed there in 1869-1870.

Another unfortunate event soon followed. Francis had a bad case of sunstroke in 1870 and, according to Mary, his character changed forever; when they came back to London in 1872 she even wanted to have him seen by Dr Forbes Winslow, a famous authority on lunacy.

He began to display the mercurial temperament and eccentric behaviour that were to accompany him for the rest of his life.

The worst consequence was that he became a quarrelsome, abusive husband. The arguments started because of his conduct towards his mother, with whom he and Mary lived in Notting Hill on their return from India.

The first violent incident Mary reported in her application in 1887 for a judicial separation took place in the November of their first year back..

Why did he have to leave India and his military career? He made the great mistake in November 1870 of complaining to the commanding General at Lucknow about being superseded in command of a company, and asked for his case to be forwarded to his regiment’s Colonel in Chief, Field Marshall HRH the Duke of Cambridge, Queen Victoria’s cousin, back in England.

The upshot of his faux pas in airing a battalion issue with the top brass was that he was put on leave of absence then, in June 1871, placed under arrest on a charge of insubordination (insulting a senior officer) and “discreditable conduct.”

He was hauled before a Commission of Inquiry of his battalion colleagues and given a career death sentence: he was required to sell his commission and resign. While he decided whether to take this relatively respectable way out, his superiors blocked the promotion he could otherwise have expected to purchase that August.

The Second Battalion of the 60th Rifles was a proud brotherhood. According to its brigade commander it was “the perfection of a Light Infantry Battalion,” with “a boundless esprit de corps pervading all ranks,” so that “it would be difficult to find its equal as an engine of war,” something the Afghans would discover in due course.

Francis had violated their covenant, and there was no longer a place for him within it.

He carried on writing letters demanding justice, including to Lord Napier, the acting Governor General, but all to no effect: “he must either sell out or be removed from the Army.” His appeals came to naught.

In February 1872 he was “removed from the Army, Her Majesty having no further occasion for his services,” so he could not even recover his family’s investment in his commissions, having continued to refuse the repeated offer of a slightly more dignified exit. Only then was he set at liberty to return to England, under a cloud if not quite in disgrace.

That was not the end of the story. Being convinced of the injustice that had been done to him, when he got back to London he continued to make a fuss, writing directly to the Duke of Cambridge and publishing in 1873 the correspondence from which most of the above account draws.

He recruited allies, and even got his case aired in Parliament by John Scourfield, the Conservative Member for Pembrokeshire, squire of New Moat and neighbour to his uncle Charles, the Tufton part of whose estate extended as far as Henry’s Moat.

Francis and Scourfield probably met when he and Mary spent part of the winter of 1872-73 at Trecwn; they shared a love of the theatre.

But none of it did him any good. Edward Cardwell, reforming Secretary of State for War, simply endorsed the decisions already taken by the regiment and confirmed by Lord Napier and the Duke.

Francis, a young and rather marginal member of the gentry class, had taken his appeal to the real Establishment, and the grown-ups had turned him down.

What did Francis Robins do next? He and Mary left England after the failure of his campaign for justice. It is possible that one of the attractions of living in Third Republic France, just recovering from the traumas of war and revolution, was that they could make their money stretch further there than at home.

French became the language of their household and of family correspondence, and they had French governesses for their children and companions for Mary (and perhaps for Francis too). Until 1876 they lived in Paris, then moved to Nice until 1881, and finally Turin, with regular trips back to Britain.

Interlude: Francis Robins Adds to the Gaiety of Nations, 1875-1876

The Robinses’ experiences in France were not altogether happy, and included one widely reported diplomatic incident which may help explain why they moved from Paris to Nice in 1876.

In September 1875, they were travelling on an omnibus from Montrouge, Francis and Mary with little Cyril and baby Winifred bouncing on their knees.

An “elderly Frenchwoman, one Madame Besse, belonging to the lower middle class of society,” sat thigh to thigh with Francis, who was, The Times noted, a former British officer and “grand nephew of the last Lord Thanet”; to the Daily Telegraph, that meant he was “a gentleman of unimpeachable honour and respectability,” which was very far from true.

At Place St. Michel they all got off and went to the waiting room for the Montmartre omnibus, whereupon Madame Besse noticed that she had lost her purse and accused Francis of taking it.

He responded in character, “We shall see about that,” and went to call a policeman, presumably expecting the same sort of deference that his social status would invite at home. He proffered his card and a letter he had received from Colonel George Henry Mackinnon, commander of the Cameronians, at the United Services Club, to prove his rank.

Instead the cops took the Robinses to the nearest police station, where they were all, including the infants, strip-searched (Francis even having to remove his boots and socks, Mary also “being obliged to let down her hair”).

Francis was then subjected to aggressive questioning. He took “how many times have you been arrested?” as a “gross insinuation,” and refused to answer, though he easily could have: “just once so far, but only by my own regiment.”

Eventually the police accepted that they were barking up the wrong tree, but did not apologise. Most of Paris’s pickpockets were English, they said, to justify their actions on the strength of one unsupported accusation.

They dismissed the Robinses with an “Allez-vous en” (Bugger off) after Francis had been bound over to appear before the magistrates if summoned. Instead he took the matter to the British Embassy and the Times correspondent, whose thorough and indignant report was extensively reprinted in the British papers.

The French press made a meal of the incident too, generally picking up the Times report and embellishing it with new details, most of them made up (including the award to Francis of another undeserved title, Sir). The story was more often interpreted as grounds for laughter rather than an apology, and the British official reaction as ridiculously disproportionate:

These are the facts in all their darkness. And it is for this reason and no other that the Foreign Office will pile up note after note, … [and] that our ambassador to London, the Marquis d’Harcourt, will be on the rack.

All the trouble spots on the European horizon will be temporarily overlooked. There will be no more Herzegovina question. The freedom of the Black Sea will be relegated to the background, the Chinese customs affair adjourned to a more propitious time; and why? Because for five minutes a French police officer saw a citizen of Great Britain dressed like a subject of the king of Dahomey.

That was not quite the end of the story. A long diplomatic correspondence had no result, so Francis was advised to sue Madame Besse, which he duly did. He eventually recovered 25 francs and she was also ordered to pay 400 francs for the costs of the trial (altogether about £17 at 1875’s exchange rate), which can hardly have given him complete satisfaction.

Keeping the Show on the Road

The Robinses racked up at least fourteen addresses in three countries (England, France, and Italy) for their growing, peripatetic household between 1872 and 1887.

Their son Cyril Hugh Sackville was born in Croydon in 1873, their daughters Winifred in Paris in 1875, Enid (known as Sybil) at Windsor in 1876, and Margaret (known as Rita) in Isleworth, Middlesex in 1882. There may also have been another child who died in infancy, probably between Sybil and Rita.

Francis did not have any post-military career. Instead, he clung to the rank and status that the Army had given him and then taken away. He came to describe himself as a Captain (or, if pressed, a “local Captain,” perhaps referring to the temporary, acting role in which he had been superseded) and as having “retired” (because he had not actually been court-martialed and cashiered).

By the 1890s the caveats disappeared, and he remained an unchallenged Captain for the rest of his long life.

How did he survive without working? The one advantage of his dismissal from the Army was that he no longer had to bear the expense of being a junior officer in a smart regiment.

That had been a way of life rather than an essential source of income. And he remained a gentleman with expectations of eventually inheriting a large estate.

Trecwn passed to his mother when his uncle Charles died, childless, in 1878. Francis’s turn to inherit had to wait 21 years, but the estate was an income- and credit-generating asset for him even before she died too.

In 1888 he spelled out the detail: his mother paid him £700 per year, which by then had fallen to just £500 net (c. £290,000, relative to average earnings then and now) because he had borrowed and spent an additional £2,000 financed by mortgages on Trecwn.

These cost him £200 a year in interest and repayments, which he had to cough up on time or his creditors could seize the whole of his allowance, as the estate was not yet his to distrain against.

So though he was not exactly poor, maintaining his lifestyle as a gentleman of leisure cannot have been easy, because it was not cheap.

It involved houses, servants, far too much drink, probably gambling too, plenty of domestic and foreign travel, and, after a spectacular and costly divorce suit in 1888, alimony of £250 a year for Mary, who was granted a separation and custody of their four children, plus half of his net income.

In 1896 the couple came back to the High Court for a return match, which Francis lost again. Thanks to these two bitterly contested and widely reported cases, we can learn more about his life and character than we could ever hope to about most historical actors who have not left any personal papers behind them.

The next two episodes of this serial will explore these two private tragedies and public dramas.

You can read the first part of House of Dogs/The Last Squires of Trecwn here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.