How to win an Oscar: filming Grassholm’s Gannets, June-August 1934

Howell Harris

One fine, bright, hot, calm Thursday, the 7th of June 1934, five people set off from the island of Skokholm in Pembrokeshire to camp for a week on the much smaller (22 vs 260 acres), uninhabited, and often inaccessible isle of Grassholm, the most westerly in Wales.

They took two tents to live and sleep in and store their equipment and supplies, including 63 gallons of water to drink and wash in, because Grassholm could not provide them with any, and 9 of cider just to drink.

They were not going on a holiday, though people used to, before the island’s owners or lessees prohibited it. They were off to make a wildlife documentary for the great producer Alexander Korda’s London Films.

The movie already had its title and its subject, “The Private Life of the Gannets.”

It would go on to gain a special mention at the Third Venice International Film Festival in 1935, and to win an Oscar in 1938, the first wildlife movie ever to receive an Academy Award.

Travellers

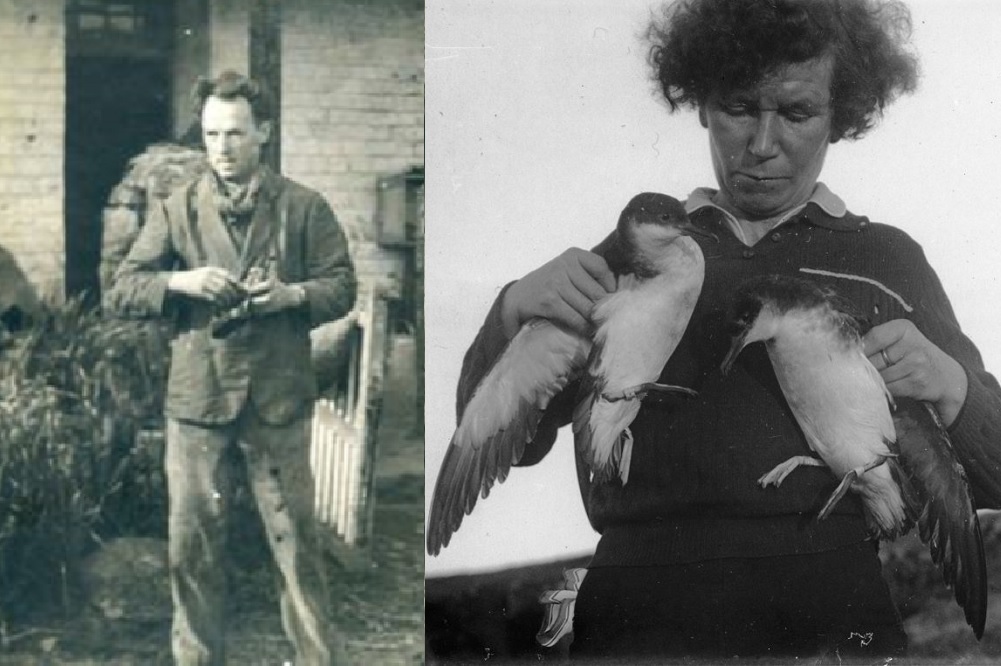

Who were these travellers? The young (31) Ronald Lockley, a self-taught Cardiff naturalist who had been leasing, living, and trying to farm, fish, trap rabbits, and be otherwise self-sufficient on Skokholm since 1927, and his wife Doris (41), a fine wildlife artist, who had volunteered to cook for the party, were the only locals.

The Lockleys had made their first visit to this special place by open boat on their honeymoon voyage six years earlier.

Julian Huxley (47), the eminent Eton and Oxford-educated zoologist, polymath, science popularizer, and public intellectual, was the dominant character among them.

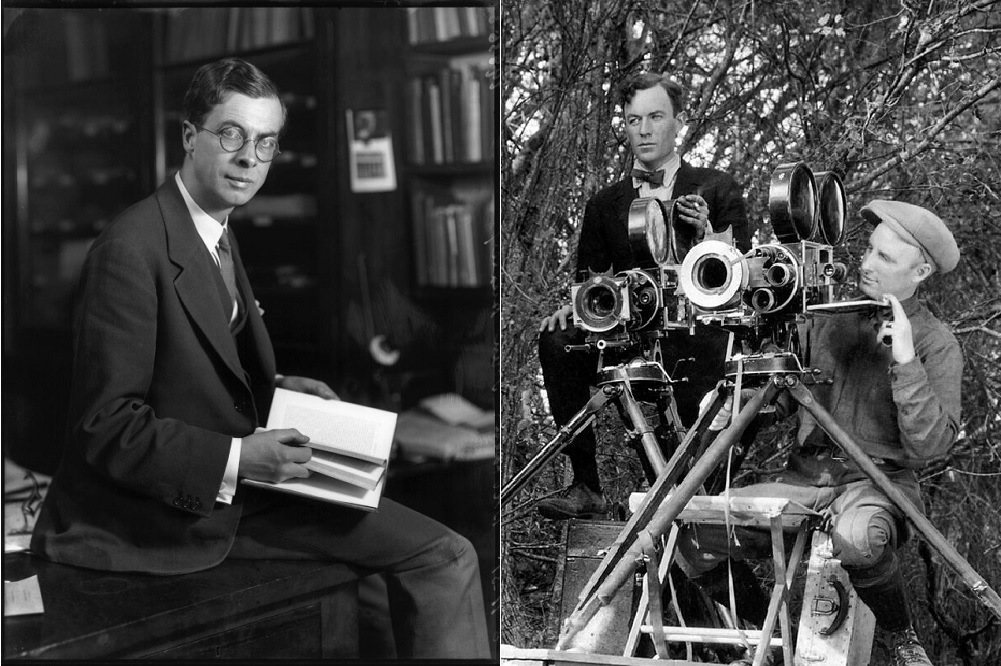

Osmond Borradaile (36) was a very experienced Canadian film cameraman who had specialised in outdoor and aerial work — the best in the business, some said. He and his talented assistant Donald Gallai-Hatchard (23) provided cinematographic expertise.

Borradaile recalled this as “one of his most engrossing assignments,” technically challenging and “among the most instructive I have ever known.”

Huxley narrated the movie in his immaculate RP voice, and gained top billing as the producer and also the writer.

Joint film

Lockley, who had left school at 16 without matriculating and still, decades later, spoke with a distinct Cardiff accent (only the first G in “going,” etc.), was simply credited as his assistant, though he believed until the first time he saw the completed film that it would appear under their joint names.

He might have thought of Huxley as his “partner in the enterprise”; but to Huxley, he was just one of his “keen helpers.”

Lockley and Huxley also disagreed about the project’s origins. Lockley claimed that it was his “long-cherished plan” and that he and Huxley had been discussing it since 1932, though there is no evidence in his diary or surviving letters that it was conceived so early.

However, in February 1933 Huxley wrote to ask if he could come to Skokholm to study puffin courtship, and Lockley agreed.

But bad weather and then the death of his father forced Huxley to postpone his trip and miss the season. Lockley suggested an alternative plan: “our taking a joint film of the island birds.”

Lockley was becoming interested in photography, and Huxley was already involved in making documentary films and using them for educational purposes. He had even taken movies of his own (on his recent travels in the USSR) that were good enough to sell to a newsreel company for public exhibition.

Epiphany

He finally arrived on the island on May 13th, and Lockley took him to Grassholm, where, Huxley claimed, he had an epiphany: it was an “unforgettable occasion … we were struck dumb with amazement: the whole area … was white with birds and their dung.

It was one of the largest breeding colonies of gannets in the world – over 8,000 pairs – and the most accessible. They were so tame that we could walk right up to the edge of the colony and even handle them, though this risked a painful peck from their large bills.”

They put on a “fantastic performance. … My reaction was immediate and definite: we must make a film of this, I said, and Lockley warmly assented.”

Whoever had the idea first, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that if Huxley had not taken such an enthusiastic interest in the Pembrokeshire islands where, he recalled, “I felt, perhaps even more than in Africa [where he had recently been on safari], the power and independence of nature”, Lockley could not have turned his own wishes into reality.

Dream Island

Thanks to the sponsorship of the publisher Harry F. Witherby, president of the British Ornithologists’ Union, founding member (with Huxley and others) of the British Trust for Ornithology in 1933, and proprietor-editor of British Birds magazine, Lockley had begun to gain the attention of British bird-watchers, amateur as well as more scientific, for his articles about the birds he observed, trapped, and ringed on Skokholm.

He won a much larger readership (and income) from his first book, Dream Island, about his first couple of years on Skokholm, which Witherby published in 1932. He had even begun a broadcasting career with the BBC.

But Huxley had contacts and credibility he could only dream of. A former professor at Rice University in Houston, Texas, as well as of King’s College London, with a long spell at Oxford in between, and most recently H.G. Wells’s principal collaborator in researching and writing The Science of Life, Huxley was a man at the heart of the British establishment who seems to have known almost everybody.

And the contact that mattered most was with Alexander Korda, without whose backing, financial support, and provision of Borradaile and Hatchard “The Private Life of the Gannets” would probably never have seen the light of day, let alone received national and international cinema distribution and recognition.

Korda later said that, of all his work, this was the film he would most like to be remembered for.

The practical side

Lockley could not bring assets like Huxley’s to the common table. So his major contribution to the joint project, apart, perhaps, from the original idea, was “the practical side,” including arranging transport of a party of five and all their gear to an island with no dependably safe landing place.

For this purpose, he drew on a local contact of his own: William Rouse & Sons, marine salvage and towage contractors of Hazelbeach on the Milford Haven.

The members of the firm were my great-grandfather, my grandfather, and his five brothers, and it was my interest in them that first drew me to this story, even though they only played a minor supporting role in it.

The Rouses had the Trinity House contract to do the monthly “reliefs” of the lighthouses on Skokholm, The Smalls, and the South Bishop, i.e. to transport supplies and carry the keepers at the start and end of their two months on, one month off tours of duty.

Grassholm

Lockley had known them since 1927 as the most regular visitors to his island home, gone on occasional reliefs with them since 1928, and relied on them to transport some heavy supplies for his own use.

He was now able to hitch a free ride for his whole party on their 10th June relief trip as the Rouses’ tug Taliesin made her way between Skokholm and The Smalls — Grassholm was only a slight diversion.

As the Rouses would only charge £14 for a special trip to come and pick them up when they were finished, doing things like this rather than by hiring a large motor boat for £10 each way saved the huge sum of £6 (c. £1,300 in today’s money) from what must have been a tight production budget.

The Tally did not just transport the film crew and their gear, they shot their first scenes of the gannetry from her deck as she circled the island as close inshore as possible.

My great-uncle William announced their arrival by blowing a loud blast on the Tally’s steam-whistle as they approached landfall, causing “thousands of alarmed gannets” to take to the wing and fly straight into celluloid immortality.

Rare sighting

Three days later the Rouses went back to Grassholm, taking family and friends with them, as they often did on a summer relief, making an outing of it.

My mother, then aged 15, was with them. In her diary she only recorded that it was very hot and she got badly sunburnt; Lockley and Huxley reported a rare sighting of a pod of 20 pilot whales just off the island. Perhaps she just did not notice.

The serious purpose of the special trip that made it worth the extra £14 was to collect the film that had been shot so far, taking it to London for processing and letting Korda and his team see how the project was going in order to give them the chance to call for more shots while the crew were still on Grassholm.

The crew was also able to use the Tally to try to film the gannets’ most spectacular behaviour, diving for fish.

Finally, on Thursday 14th June, the Tally went back to Grassholm again, and picked up its five visitors for their return to land with most of the movie’s raw footage safely in the can. Their island idyll was ended.

I could not escape the feeling on those glorious mornings at Grassholm that I was living through a vivid and beautiful dream. These were most truly the halcyon days, free from all care, rich with sunlight, blue sky, and clear, quiet sea, the companionship of a few chosen persons, of half-tamed wild birds, of seals and porpoises, and of the sun-warmed rocks; and we had the long green grass for bed. [Lockley, I Know an Island, p. 82]

Bird’s eye view

But the project was not over. London Films decided that extra scenes were needed, so Gallai-Hatchard and another promising young cameraman, John Taylor (20), were sent back to Skokholm in August to stage close-up shots with gannets Lockley captured on Grassholm. One was even shipped to Elstree Studios for some more elaborate fakery.

Korda also wanted some aerial shots, so Borradaile came back to film them from the front hatch of a new Supermarine Stranraer flying boat provided by the RAF base at Pembroke Dock after Korda had pulled some strings.

The plan was to provide a bird’s eye view, as if from a gannet returning to its nest.

The result was, in Borradaile’s words, a “beautiful, exciting shot, quite avant-garde for its time,” well worth the risk to the Stranraer and its crew and the death of the birds killed as it power-dived through a snowstorm of them, startled into flight.

This provided the film’s opening sequence.

The crucial slow-motion footage of gannets diving to fish that closed the film was also shot later, by a contact of Huxley’s and Lockley’s, the cameraman and director John Grierson, ‘father’ of the British documentary movement. Borradaile and Hatchard’s Grassholm version cannot have been sufficiently spectacular.

Grierson filmed his in the Firth of Forth instead from the deck of the same Scottish vessel that featured in his pioneering documentary “Granton Trawler,” also released in 1934.

They were the gannets of Bass Rock, but they stood in perfectly well for those of Grassholm. He did the job in an afternoon.

Cruel

Lockley got his first sight of the finished work at the Zoological Society of London, where Huxley was in the process of being appointed as Director, in early November.

He “thought it rather cruel of Huxley to allow himself all the honours on the title of the film… After all the whole idea was mine & he only stepped onto the island … with everything arranged by me.”

He tackled Huxley about it, and his partner wrote to Korda to get the title changed to reflect their earlier 50:50 agreement, but it was too late.

So just before Christmas the Lockleys attended the premiere at Leicester Square — a grand affair, with the “Gannets” receiving “prolonged applause … at the curtain.”

He was very happy with the way the film turned out. It helped make his name, and put Pembrokeshire’s bird islands on the map as a natural wonder.

But Huxley’s treachery still rankled. Though they remained friends, collaborators, and quite frequent correspondents until Huxley’s death, Lockley never forgot.

After Huxley died his widow tried to smooth things over, offering Lockley the Oscar to keep, but by then it was too late.

Suggested Reading and Viewing

Ronald M. Lockley’s I Know an Island (Harrap & Co., 1938), pp. 76-84, is the best as well as the longest participant account of this project.

Huxley’s Memories 1 (1970; Penguin ed., 1978), pp. 208-11, covers it from his perspective, as does Borradaile’s Life Through a Lens: Memoirs of a Cinematographer (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001), pp. 51-3.

More information is supplied by the Lockleys’ daughter Ann in her Island Child: My Life on Skokholm with R.M. Lockley (Gwasg Carreg Gwalch, 2013), pp. 46, 49, and esp. 58-9 on his anger at not sharing the credit equally with Huxley.

The best secondary account is Gregg Mitman, Reel Nature: America’s Romance with Wildlife on Film (Univ. of Washington Press, 2012), pp. 76-9.

The film should be watched on the British Film Institute’s site. YouTube’s version is lower quality and has the commentary re-voiced for the American market.

Read the other installments of the Gannets of Grassholm here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.