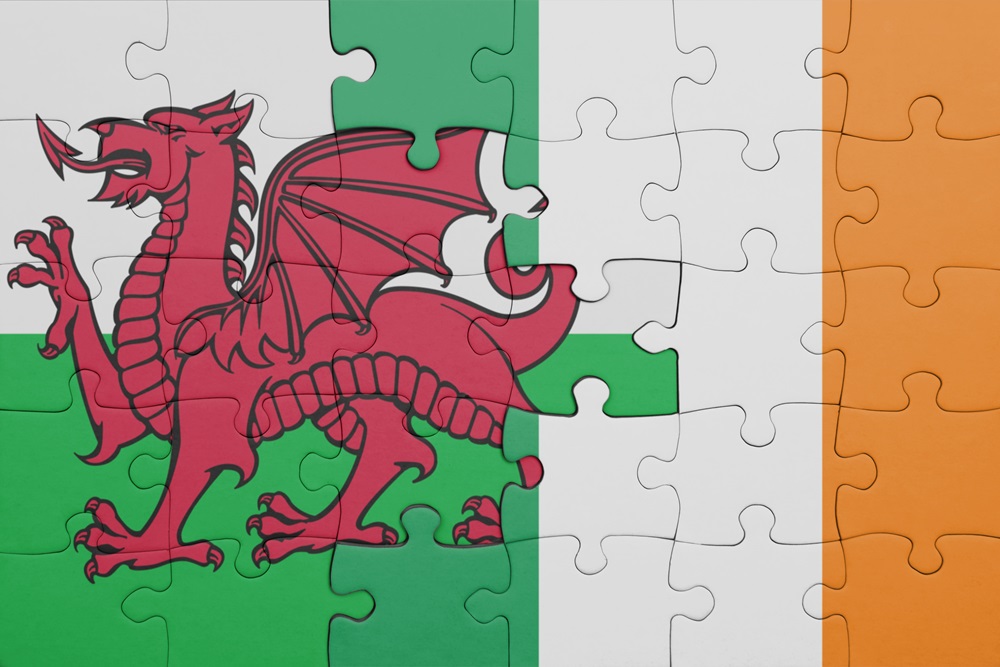

Ireland, Wales and the scholar who helped unravel their Celtic connections

Simon Rodway, Lecturer in Celtic Studies, Aberystwyth University

Ireland and Wales share more than just geographical proximity; they have deep cultural and linguistic connections. And this year marks the centenary of a groundbreaking work which explored the relationship between the two countries.

Ireland and Wales: Their Historical and Literary Relations was written by the Irish scholar Cecile O’Rahilly in 1924. Her legacy in the field of Celtic studies continues to resonate, 100 years after her book was first published.

The Welsh and Irish languages are close relatives, descended from a common Celtic ancestor. It seems plausible, if much less open to proof, that the Irish and Welsh also inherited cultural and literary features from their Celtic-speaking ancestors.

One striking example is the role of the professional praise poet, a revered figure in both Irish and Welsh societies. Classical authors note that poets in ancient Celtic Gaul (present-day France, Belgium and Luxembourg, as well as parts of the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland and northern Italy), held a similarly esteemed position. The word for “poet” in Gaulish, bardos, shares its roots with the Middle Irish word bard and the Welsh bardd. It’s a linguistic link that underscores their shared cultural heritage.

Celtic culture

Irish literature offers vivid examples that closely mirror classical descriptions of ancient Gaulish society. Notably, warriors were said to keep severed heads as trophies and fierce competitions to the death at feasts determined who would claim the choicest cut of meat. These examples led to the theory that a relatively uniform Celtic culture once spanned the Celtic-speaking regions of antiquity, with Ireland preserving these traditions the longest, partly due to the fact it never became part of the Roman Empire.

Wales, on the other hand, was profoundly altered by its absorption into the Roman province of Britannia. The medieval Welsh adopted the Trojan Brutus as their ancestor, and idolised the Roman general Magnus Maximus.

The Welsh word Gwyddel (Irishman) derives from gŵydd (wild), and so literally means “savage”. The gulf between Irish and Welsh was facilitated by the fact that major phonological (the sounds in a particular language) changes to both languages obscured their historical relationship. No doubt the 7th-century Irish who borrowed the Welsh word Gwyddel as a term of self-definition (it gives us Gael today) were blissfully unaware of its original meaning.

Despite the fact that the medieval Welsh saw the Irish as being just as alien as the English, they were in frequent contact with them. There were Irish-speaking communities in parts of Wales, until the 7th century, as can be seen principally from bilingual inscriptions carved into stones in Irish and Latin.

Welsh churchmen such as the family of Sulien of Llanbadarn Fawr, 11th-century bishop of St Davids, were educated in Ireland. And Gruffudd ap Cynan, king of Gwynedd from 1081 until his death in 1137, spent his youth exiled in Ireland. He returned to north Wales with Irish soldiers to reclaim his throne. Day-to-day commerce across the Irish sea is also reflected in both Welsh and Irish literature.

Cecile O’Rahilly

Born in 1894 in County Kerry, O’Rahilly’s academic journey began in Ireland but her work soon took her to Wales, where she won a scholarship to pursue a master’s degree at Bangor University. She submitted an essay to the National Eisteddfod Welsh cultural festival in 1920 and ended up winning. The essay was the seed that grew into her seminal book, which explored the complex relationship between Ireland and Wales during the middle ages.

1/ Cecile O’Rahilly (1894–1980), appointed Assistant Professor in the School of Celtic Studies, DIAS in 1946 & Professor in 1956, was a talented scholar in all periods of the Irish language, who left a deep and lasting impression on the field of #CelticStudies #DIASdiscovers pic.twitter.com/iHRnTaToHM

— DIAS_SCS Library (@SCSLibrary) May 25, 2020

She remained in Wales, teaching French at a number of different schools, until 1946 when she took up a post at the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. She later became a professor there, the first woman to hold the post. O’Rahilly lived in the Irish capital with her Welsh companion Myfanwy Williams until her death in 1980. She is best known today as the editor of the epic Irish saga Táin Bó Cúailnge (the Cattle-Raid of Cúailnge), released in 1967.

O’Rahilly did not return to the question of the relationship between medieval Ireland and Wales in print. Nonetheless, her work was pioneering, but it also opened up debates that continue to this day.

Debates

Among the discussions arising from her work, scholar Proinsias Mac Cana and others, posited plenty of Irish influence on Middle Welsh tales such as Branwen, one of the earliest surviving Welsh prose stories.

But given their shared heritage, some similarities might date back to prehistoric times rather than the medieval period. They could also have arisen by independent generation, or have been independently borrowed into the two traditions from a third source, such as Latin literature, for example. A colleague of mine, Patrick Sims-Williams, has shown that it is difficult, if not impossible, to choose definitively between these possibilities.

This article was first published on The Conversation.

![]()

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

In Wales we seem to give too much bandwidth to Irish influence upon Wales and very little thought to the effect Wales had upon Ireland eg Christianity. Perhaps Wales saved western civilisation?

The mention of Brutus and Troy is interesting as it may not have been adopted if the geography of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey are actually based in NW Europe – “Where Troy Once Stood” Iman Jacob Wilkens.

I agree. Well said. People forget that we Welsh Christianised Ireland, and they in-turn celebrate now a Welshman Saint Patrick whose real name was Maewyn Succat. His first language was not Gaelic but Old Welsh. He was educated in Latin which at the time was the scholarly language used by the likes of Gildas , Nennius & Saint David ect….

It’s frequently overlooked that in hilly and/or boggy terrains and in an era when good roads were largely absent – Roman military roads in Wales were relatively few and weren’t systematically maintained after the legions left – sea travel, at least in calm weather, was often easier than land travel for those who had the navigational skills.

So it’s no real wonder that there was a fair degree of contact, both ways, between communities on the west coast of Wales and on the east coast of Ireland.

The fishing boats of Abermaw criss-crossed the water to Arklow, Wicklow, Howth and Malahide on a regular basis in the 60’s and 70’s, nothing like steaming past the lights of the towns mentioned a few miles offshore on a dark and starry night… RIP Keith A… A teenager when the troubles started, I assumed that the big battle between England and Ireland would be fought on the beaches of Ardudwy… or so I hoped, so I could put my plan to occupy Pen-y-Dinas Hillfort, into action… A year later I had a walk with my thumb out around the South… Read more »

That’s a bit of more recent history which I didn’t know!

Entirely agree that the influence of Irish traditions on the Welsh traditions is over emphasised. The narrow sea between the two afforded two-way traffic, so a tale or poem clearly appearing on both sides cannot be sourced as one or the other origin without evidence. I think this Irish emphasis goes back to John Rhys, first Prof. of Celtic at Oxford (1880s). He thought the Irish traditions were primary because much more has survived (So?) and the lack of Roman mixtures. The latter just means a different culture for Wales, not an inferior one. Paradoxically Rhys, Anwyl and later Welsh… Read more »

Simon thank you for a characteristically clear and friendly account of this fascinating topic. One item puzzles me particularly. In the Mabinogi of Branwen, which you mention, we have a quasi-historical account of total war between ‘Britain’ and ‘Ireland’. So appalling was it that it merits the term genocide, as almost all fighters on both sides were massacred. The tale may well exaggerate the scale and scope. Locations mentioned are in Gwynedd in Wales (for ‘Britain’) and Leinster (Ireland). While genocidal massacre might be exaggerating there seems to be a notable war remembered on considerable scale. But as the Mabinogi… Read more »

As I understand things the first person to work out that the languages of Britain and Ireland and Breton,exceptingemnrd English,were closely related was Edward Llhwyd.He also cristened these languaes Celtic but on what evidence I do not know.