Letter from Crymlyn Burrows

Suz Mendus

There are nine circles to Crymlyn Burrows, a Site of Special Scientific Interest slipped between Swansea’s Fabian Way and the Bristol Channel: the horizon, the sea, the strandline, the sand, the dunes, the marsh, the bog, the pond, and the fen woodland.

These circles whisper its history and prophesise its future. But at first glance it’s hard to believe there’s life here at all.

In the 1960s, the brackish marshland of Crymlyn Burrows lay under eight million tonnes of boiling crude oil. Though the BP petrochemical plant is long gone, a keepnet of industrialisation still circles its border: a sulphurous breeze from Gower Chemicals; the mangled remains of a Network Rail yard; the exhausted wasteland of Tir John Landfill. And, looming behind four clogged arteries of traffic on the A483, a watchtower of capitalism: an 800,000 square-foot Amazon warehouse.

Over the road, at Crymlyn beach, a sluggish horizon beaten by a storm is lumped on a cold slab of the channel. Its weight flattens the ebbing sea to a shallow wave of foam, drooling hopelessly over an expanse of concrete sand.

It licks at an eight-kilometre-long serpent of black bladderwrack, tantalising and out of reach. This stygian strandline hosts many shades: fishing line ligatures, Fireball Whisky miniatures. Lost flips, mislaid flops. Walkers packets, snared by the weed for embellishment, shimmer in a chill breeze. Were the packets to make an escape to the dunes, they’d have to navigate the vast no man’s land of cold, compacted sand first.

The area was razed by plundering oyster boats in the 1910s. It shows. Ribs of empty razor shells crack under foot. The great sheaths of the bivalves are ridged by time, like the weathered fingernails of Penclawdd’s cockle fishermen. The prickly cockles are empty too – just their sharp, studded shields remain on the nothingness. A hundred-years old oyster shell is riddled with holes: the dull, excruciating work of a sponge which bores slow cavities into molluscs.

The number of times this shell has witnessed the moon rise, and the sun set, been kneaded by hungry and full tides, tumbled in storms, sucked under, and spat out, pales in comparison to the coastal coal. Since the Mesozoic Era, when nothing existed to decompose trees, these chunks have been rolled and shaped into use by the seabed, morphing from trunk to coal towards the end of a 250-million-year purgatory.

But, between the circles of the strandline and dunes, there are little things, surviving. A felty pink blanket of hornwrack swaddles the bulging mermaid’s purse of a thornback ray, no longer attached to its soft seafloor nursery. The fluffy hornwrack appears as a dead weed, torn up by tides, when in fact, it’s a colony of thousands of living, unified zooids.

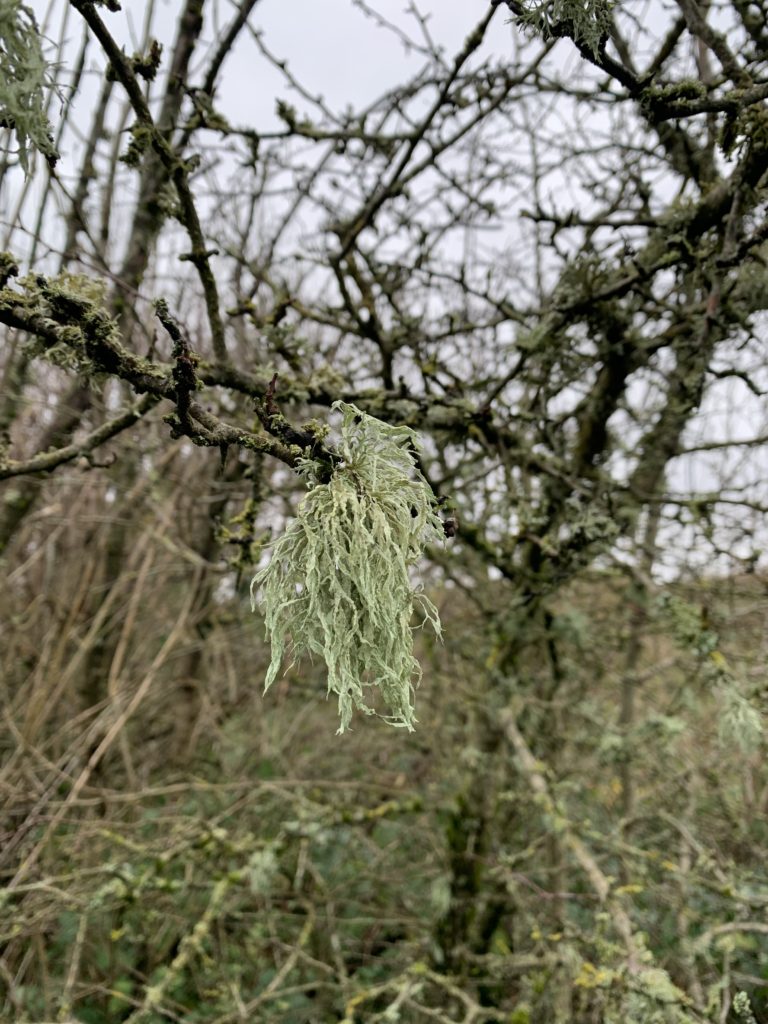

A waterlogged stick is flocked with a synergetic reef: blooms of marrowfat algae, frosts of sea glass lichen, sage petals of lobed fungi. This seemingly inconsequential cylinder of life dwelling on the dead reflects Swansea’s fluctuating but improving air quality.

There are few breaks in the strandline. Everything here must cling on to survive or be whipped to the dunes.

Charonic sea winds ferry debris from shore to marsh, blasting tonnes of salted sand to the steep, parched dunes in their wake. Sea rocket, prickly saltwort, and sea holly seeds fight to germinate, piercing the dry chokehold of the sand. Spines of marram grasses roll inwards in thirst, hoarding what moisture they can, to form freezing, tufted braces of brittle needles.

Buried under the sand, battered driftwoods and roots collaborate to stabilise the dunes, anchoring their environment to prevent it sliding back toward the beach, forever.

Behind the rampart of the dunes, waits the underworldly salt marsh: a spongey and acidic slap of land between the River Neath and the beach. Ten thousand years ago, the area was a coastal plain roamed by grazing beasts. Bison and reindeer nibbling, plucking, munching, squelching, would encourage regeneration. With the beasts vanished, native plant species must persevere against intruders in their ever-evolving ecosystem.

Nowhere is this more evident than a large mound in the marsh, fraught with superstition. Jaundiced snail shells circle the mound’s basecamp. An abandoned ochre grub casing lies among them – perhaps the larvae of a blood-red, flint-black cinnabar moth, the caterpillars of which survive on noxious ragwort to become poisonous themselves.

The mound is littered with the depleted. Leaf skeletons, splintered twigs, and bedraggled feathers are all skewered at angles on the ascent. Their Sisyphean struggle is scrutinised by a pernicious ruler: a ghostly wild parsnip, whose sap combined with sunlight causes blistering flesh.

But the mound’s foot is fringed with fresh fronds of velvety hedgenettles, their small leaves cradling crystal ball raindrops. A spike strip of star moss makes its way under thorny vines strapping down the landscape, dodging flames of red dandelions studding the sand. The young moss continues its creep beyond woolly purple ferns unfurling skywards, bypassing the stack of decay, in a fragile endurance against the odds.

Past the mound, a skeletal hand rises from the ground: the silvery twigs of a solitary Japanese rose. The only way to kill this invasive species is to bury it alive. Freshly dug graves line the approach to the fen woodland.

The native alder is hungry for the wood’s waterlogged conditions. It clutches round, toothed leaves like coins offered to the gods. Ancient branches and wizened trunks cloak saplings and snags in Spanish moss as they watch an apple tree sink into the bog.

The apple tree is a mass of hoary branches, its trunk invisible, submerged in soggy limbo. Desperately, the branches cling on to small, ripe fruit as if to appease whatever clawed a herring gull to shreds at the tree’s base, leaving the feathers for the umber mud to swallow.

Lilac buds and wild carrots peer from the forest elders’ mossy cloak. They scatter beyond the wood towards the reedbeds – one of the most endangered ecological environments. In the reedbeds there are more feathers, this time animated with twips, chirps, chiff chaff and chip chips.

These are the feathers of buntings, water rails, mute swans and little egrets, finding solace within the Burrow’s circles. Pied wagtails with their humbug stripes sigl-di-gwt through the tidal creeks, and fuzzy pellets on squidgy ground mean there could be buzzards nearby. I’m told that last spring there were a thousand toadpoles in the pond near the apple tree.

There’s hope in the gorse flower stars, golden and bright against the camouflage of decay. And there’s hope for the warblers nesting inside it too.

The circles of Crymlyn Burrows offer a spectrum of life, from that which is waiting to die, to that which has not yet been born – and the fight for survival in between.

As humans attempt to mediate their own damage and drive efforts into conversation, the future of the Burrows is more certain than it was years ago. But the very uncertainty the landscape is so used to – and its adaptation to endure through change – persists in its behaviour.

Despite its environment of chaos and struggle, there are little things everywhere, surviving.

In fact, instead of an underworld, perhaps Crymlyn Burrows is more of an Elysium, just off the A483.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Wonderful writing! Brava, Suz.