Letter from Presteigne

James Roberts

I’ve been worrying about swifts. Their numbers seem to be much depleted this year. I’m not sure if anyone monitors them in our town each summer, but there certainly seems to be less of them at the moment.

One July evening last year I counted 50 circle-diving above the town, a vortex of birds. But this year I’ve only counted 5 so far.

I’m not sure if this is something to worry about, but worrying about the wild is my superpower. In other places nearby there seem to be big concentrations of the birds. Driving home from Hereford a few days ago I travelled beneath a flying carpet of swifts, hawking over an old orchard, hundreds of them weaving between the apple trees.

I’m now sitting in a graveyard watching them more closely than I’ve ever done before.

Are swifts drawn to the dead? I have no idea, but graveyards have been the places I’ve seen them most.

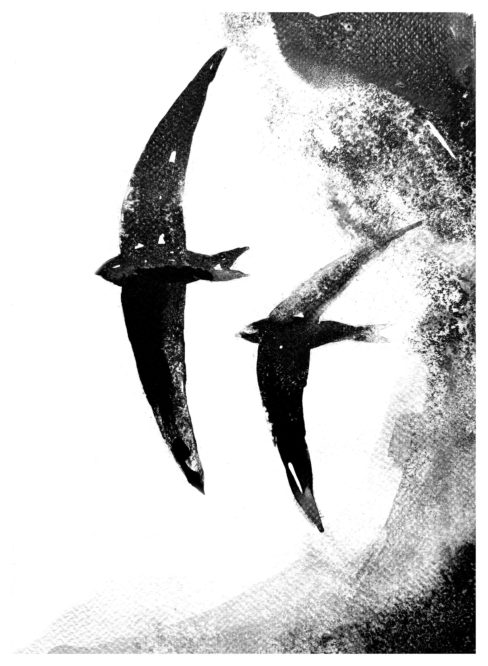

Little Scythes

In Clyro they gathered above the church steeple at dusk, little scythes against the rising moon. Their speed and agility is, of course, otherworldly.

They’re so fast that they probably cut holes in this world and appear briefly in the next.

There seems to be much negotiation among biologists about whether or how swifts sleep. They don’t roost at night and therefore it’s thought that they sleep on the wing, climbing high to spiral slowly down while taking a snooze.

This may not be the case. There are surely beds for them in the roof gables of heaven every night, or, at least, swift boxes attached to the pearly gates.

Some scientists are convinced the birds can switch off certain regions of their brains in sequence, thus allowing a form of sleep while other parts stay active.

I too can do this, for long periods of time, switching off the parts of my mind which, for instance, know what to do with clothes mountains on bedroom floors, or deal with any form of accountancy, financial or otherwise. So, I think this is a possibility.

Presteigne is another market town close to the border, near Offa’s Dyke. It’s better kept than Kington, more well-to-do. There are gardens filled with honeysuckle, pavements sprouting pristine pink hollyhocks 8 feet tall or more, and many beautifully preserved old houses with prominent gables – perfect for swifts.

They swoop along the line of the church walls, plunge into the air above the graves, then rise and clatter, and finally fold into their nest holes. Some hang at the entrances, clinging with their moth-delicate feet as they drop food into the sack mouths of their young. Twenty, thirty, forty of them.

Recently, on a visit to London, I saw rose-ringed parakeets perched on a roof aerial. Their long forked tails and bright colours were as exotic as African dancers. As they flew off they left a confetti trail of colour against the grey London sky, a sky that made them seem utterly out of place.

Swifts are also exotic dancers, though they seem almost too exotic to be associated with any continent, country or region. Is there any being less attached to the earth than a swift? They’re wholly of the sky, and therefore out of place everywhere, because skies move from place to place.

No slowing down

Leave – return, leave – return, it feels endless this process of rearing their young. At no point do I see them slowing down, tiring, taking a break. There’s no modulation, no change of pace. I’ve never seen a dead swift but I’m told that many of the young don’t make it into the air.

They leap from their nest holes not quite ready, and end up on the ground, twitching and flicking until the cat finds them. But what happens when the end comes for those who do make it into the sky? I guess they just shut down mid wingbeat, hit by a bullet, then spiral earthwards like fighter planes, smoke pouring from their tails.

Or burn up in the atmosphere like minuscule meteors. Or perhaps they’re granted some special grace and instead of falling they rise and form tiny swift clouds floating through space. They could be out there right now, in high orbit above Jupiter. These scenarios are likely.

Leave – return, leave – return, that’s the constant, but the method never repeats. I’m trying to keep my eyes on a single bird, to watch its path to and from the nest. The hole is in the apex of a steeply pitched roof belonging to a terraced house so narrow I’m sure the owners can spread their arms like wings and touch both side walls.

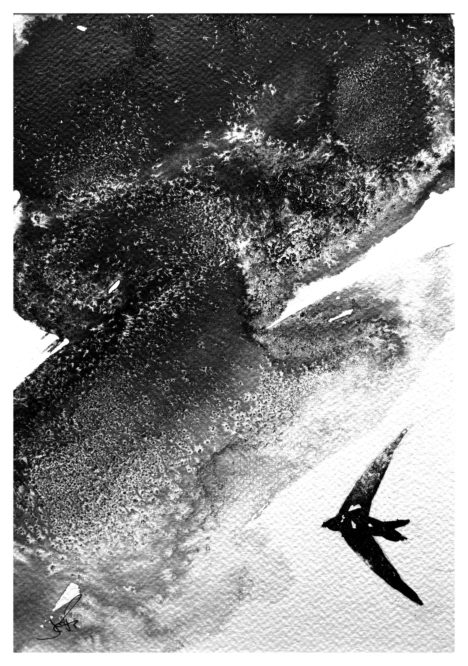

The bird ripples out into the air and is off, over the church and surrounding trees, scissoring the invisible streamers of its fellows who are busy setting fire to the air. And then it’s gone over the roofs and over the fields, over the mountains and over the sea, following the strand lines of continents, the shining lace of rivers.

It picks a thousand choice insects for its young and then returns, outrunning the spin of the earth – over the sea, the mountains, the fields, the roofs. It reappears, whirrs down and thwacks into that tiny hole. The chicks feed, it leaves again. Two minutes have passed.

Hyperactivity

I’m getting a migraine, watching all this hyperactivity. And I’m feeling my age, which is an ache to be able to run again – full tilt. This I tried to do in the lane last summer, on a quiet evening when I was sure there was no-one about.

No preparation, no limbering stretches, no jogging on the spot to warm my muscles. I just ran in my boots and jeans. Flat out. It felt wonderful. My thoughts poured out the back of me like exhaust fumes. I felt my muscles burn and that sense of take off I used to get when I was an athlete.

When a sprinter runs flat out they spend almost the whole time in the air. Tragically it didn’t last. My lungs reminded me loudly of all the cigarettes I’ve ever smoked. My heart played the bongos. Then I felt a knife cut to an ankle. I wheezed to a halt then hobbled for nine months until my achilles tendon healed.

It was almost worth it.

I love to watch Usain Bolt run. He’s the most elegant of us, and, when he raced, the most alive. What would that feel like – when your body flies beyond the limits of a whole species?

Wonderful I’m sure. So what then does it feel like to fly like a swift?

Precipitous

Yesterday evening we drove across the mountains from Tregaron to Rhayader along a winding, precipitous road which allows for a top speed of slightly more than walking pace.

While we drove we saw two men paragliding along a ridge, floating serenely to the side of us as we passed, so close I could see the crumbs on their lips.

I’m sure they were happy up there, human ballast, swinging in space beneath their huge fabric wings, moving hour hand slow over the mountains.

We talk so much about the pace of human life, our frantic activity, the busyness of business. Is this really the case? As the paragliders floated away like jellyfish lost to the tide, a swift appeared, scissoring the space between them.

It plunged down towards the car, and played chicken with us for a second, rushing at the windscreen. We were eye-to-eye for a time so short my brain didn’t register the fact before the swift had passed into the next county. Or country.

We’re bovine slow we humans, ballast slow. After the swift tore over the summits a line of motorcyclists cruised past us, old men with long white beards, bellies resting on their fuel tanks. Some sported motifs embroidered on the backs of their leather jackets. I think one of them read “Live fast, die young”. I’ll admit, we giggled.

Impossible

The swifts continue to skelter above the graveyard and I’m getting exhausted watching, because I’m still trying to follow them one at a time, tracking their impossible journeys. My brain signals are getting tangled, synapses misfiring. I think I’m about to blow.

I look away, at the trees and stone walls, at the ancient steeple which hasn’t moved a millimetre in five centuries, at an old man bent over his work painting railings.

One brush stroke, pause, one brush stroke. A swift screams, demanding his attention. The old man smiles, but doesn’t try to look up. He’s happy just to know that they’re here for one more of his many summers.

James Roberts publishes a weekly story via his newsletter – Into the Deep Woods

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.