Letter from Zagreb

Martin Shipton

Forty years to the day after the death of Richard Burton, I joined a walking tour in Zagreb, the capital city of Croatia, that focussed on the life of one of the most significant historical figures the Welsh actor portrayed during his sadly curtailed career.

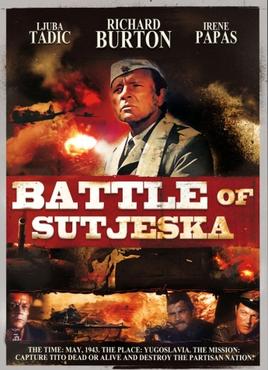

In 1973 Burton starred as Josip Broz Tito in a film called The Battle of Sutjeska. It depicted a crucial World War Two engagement that saw 20,000 Partisans led by Tito break through a line of 120,000 Axis troops in the mountains of Bosnia.

As a result, the Allied powers switched their support from the royalist Chetniks to the Communist Partisans – a decision which led to the Communists taking power in Yugoslavia after the defeat of the Nazis. Tito ran the country from the end of World War Two until his death in 1980.

Tito has long been a hero of mine. I remember being on a train from Hungary via Yugoslavia to Italy in 1986, seeing teenage Yugoslavs board the train and travel freely on weekend trips to Trieste and Venice.

They were grateful to Tito, who had died six years before, for introducing a form of Communism in which citizens were allowed to travel freely to the West. This was in stark contrast to the way other Communist regimes in eastern Europe – part of the unacknowledged Soviet empire – kept their people behind the Iron Curtain.

Stalin

Tito had courageously stood up to Stalin and refused to go along with the repression that was commonplace in the Warsaw Pact countries. He also managed to keep together a disparate group of nationalities under the federal umbrella of Yugoslavia throughout his time in power.

His philosophy was based on a form of bottom-up Socialism, where people at a local level tried to work out how to solve social problems affecting their communities or industries.

They were guaranteed a job and a place to live.

One of the great tragedies of the late 20th Century is that within a few years of Tito’s death, the politicians who came to power were those who sought to exploit racial differences for their own advancement. Such rabid and divisive nationalism led to civil wars and deaths on a scale unseen in Europe since World War Two.

The race riots we have seen in Britain over the last week stem from the same divisive beginnings, and those responsible should be dealt with harshly.

EU

The taxi driver who brought us to our hotel from Zagreb Airport – a man probably in his late 50s – was an admirer of Tito’s, even though he had been just a teenager when Tito died: “In Tito’s time many thousands of workers were employed in factories between the airport and the city, but the great majority of those jobs have gone,” he said. “The EU may be a good thing for the larger countries who are members of it, but Croatia has just become a new market for them.

“In each of the six countries created from the former Yugoslavia, there is a serious problem with corruption. In Tito’s time, if an official or factory manager was behaving corruptly, they would end up in jail.

“Younger people today refer to Tito as a dictator, and say he was undemocratic. But so far as I am concerned, democracy is just another word for capitalism.”

For years, right wing politicians in Zagreb had wanted to erase Tito’s name from the city map. In 2017 they succeeded in changing the name of Tito Square to Republic Square. This spurred journalist Danijele Matijević to devise a project that would enable ordinary people to learn about Tito and his legacy by walking in his footsteps through the city.

Danijele has skin in the game: two of her grandparents were Partisans. For more than two hours we listened to her tales about Tito as we walked from site to site of significance to his struggle against the fascists – both German and a homegrown variety known as the Ustaše, who were installed as a puppet Croatian regime. The Ustaše enthusiastically embraced the barbaric cruelty of the Nazis to the extent that even some of the Nazis regarded their behaviour towards victimised minorities as too extreme.

Danijele was born two years after Tito’s death, so has no personal recollections of the revolutionary’s rule. She was, however, a member of the Pioneers – a Communist youth movement whose members dressed up in a specially designed uniform and were taught about the value of the collective as opposed to the individual and the value of international solidarity for the benefit of the repressed.

Revisionism

Danijele laments the fact that Croatia is now – at least for politicians who control the flow of information – in an age of historical revisionism, where everything that Tito achieved is regarded as bad and Yugoslavia should never have been created out of the remnants of the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empires.

Yet my conversation with the taxi driver and with Danijele herself demonstrated that despite all the efforts of the right wing to eradicate Tito’s legacy, he remains for many an admired figure who never wavered from the two great missions of his life: to defeat fascism and to create a better society for Yugoslavs as a whole.

While clearly an admirer of Tito, Danijele is determined to give a rounded portrait of him to those who join her walk. There were instances when he engaged in authoritarian behaviour, treating some dissidents with excessive cruelty. As he got older, he encouraged the building of a personality cult around himself. And his failure to engage sufficiently in succession planning meant that it was easier for divisive nationalist politicians like Slobodan Milošević to come to power and make civil wars inevitable.

Yet despite these shortcomings, there is much to admire in the positive achievements of Tito, who was an inspiration to many leaders who took their nation to independence from colonial powers like the UK.

Elizabeth Taylor

Let’s allow Richard Burton the final word. In 1971, when the film he was going to star in was in its planning stages, he and Elizabeth Taylor spent some time with Tito at the President’s home on the Croatian coast.

Burton wrote in his diary: “Last night we went to see a film in the Roman Theater at Pula. The streets were lined with sailors rigidly at attention, behind them masses of people who applauded the whole route. E [Elizabeth Taylor] was the star of the evening—much more so than, or at least equal to, Tito. When we entered the coliseum – 6,000-person capacity – they all stood up and gave an ovation. E deeply thrilled. Me cynical as ever.”

Information about the Tito walking tour, which costs 20 euros per person, can be found on Danijele’s website at: https://walkwithtito.com/

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

I lived in Zagreb from 1979 until 1984 during my first marriage since my spouse was from Zagreb and, incidentally, a great supporter of Titoism.The racism and xenophobia between Serbs and Croats was blindingly obvious to me before Tito died. I remember being screamed at by a shop owner in Zagreb when I enquired whether they stocked a delicious brand of Turkish delight I had tried on a visit to Belgrade. “We do not stock Serbian muck!” was the response. I also experienced massive racism and hostility as a British woman out there, especially from the workers’ union in my… Read more »