Oi! I walk past my great grandfather’s farm

Richard Davies

It was a shout resounding through my childhood. I’d be walking across a field mushroom picking in the half-light or climbing over a barbed-wire fence with my mate Gareth in tow to get to a tree with a crow’s nest in it. There would be an angry shout – Oi – and we’d start running.

A farmer would be waving angrily at us – it was great fun. We were on his land – although it wasn’t his land; it was on the Mynydd Marchywel estate and he would have been a tenant farmer.

My family had been tenants on this mountain for generations. Small, miserable mountain sheep farms from which they tried (and mostly failed) to wrest a living.

The land was boggy and the soils thin. It was a hard living and most of the men ended up working extra shifts in the deep mines of the Dulais valley for a bit of real cash or tunnelling the short dangerous drift shafts that were burrowed into the steep escarpments along the sides of the Vale of Neath.

My grandmother recalled crying when her father took the family from a house which had a bath with hot water in the metropolis of Crynant to a farm called Blaenhonddan, which had no water apart from an outside spring and was on top of a mountain with five walking miles to the school of the same name every morning.

Brambles

I grew up with the bones of this farm rotting in brambles. Her father had been forced to abandon the business and move to the Caerau above Maesteg following his youngest son Nye to another sheep farm when he got too old to manage on his own.

There were no assets to sell apart from a cow and couple of old horses. The girls had married miners, the boys gone into trades. The family moved on.

Nye continued farming into his nineties. His sons and grandsons on a different mountain. I doubt if they paid inheritance tax.

Farmers are different.

They are not exceptional.

I get the mindset. Leave me alone and I’ll get on with my life and don’t tell me what to do, until I need society: education, health, a road to market.

The farming community is outraged that some of them are going to pay a reduced inheritance tax on their biggest asset – land. Not that many of them in Wales at least are going to have to pay much – and over ten years interest free.

It sounds a reasonable deal to me. But farmers are of course exceptional; it is a tough job – they work all the days of the year – they do – you have to on a farm – it is a lifestyle business – and what a lifestyle. I’ve seen farmers on tractors spreading slurry at all times and hours.

Methane

There’s a farm above the beach on Poppit Sands at Aberteifi who seems to time their shit spreading to the start of the holiday season to welcome the visitors from the valleys and England.

There’s a regular roll of methane over the beach in the summer when the winds’ from the South which must play havoc with its Blue Flag status. The water’s fine but the fumes will kill you.

The farmers in the Teifi valley have spread so much shit on the land the run-off has killed most of the fish in the river.

The Wye has become a drain for chicken guano in some areas, decimating the biology of a watercourse.

Wild swimming – you’ll certainly be wild if you accidentally drink any of it.

The cows in west Wales have largely disappeared inside large barns as the cows, who we are assured, prefer it inside in the winter.

Thousands of years of evolution of a large, socialised, herd grazing animal have been reversed in a few years because you can get more milk out of the beast inside.

Some farmers are looking after the countryside so well they have managed to industrialise it – the fields have so much shit and fertiliser on them they glow in the dull winter light of January.

Grass shouldn’t be that colour surely. Or is it global warming?

Guardians

This is all difficult for Wales. We’re not supposed to criticise farmers. They are the guardians of the countryside, they provide all the food, they don’t pay any inheritance tax.

They’ve got huge assets but little cash.

Most of the Welsh rural population have little cash and no assets.

How do you get into farming apart from marrying into it? There’s no chance of young landless farmers to enter the business as anything but tenants as the land prices are hugely inflated by the options of investors using land to avoid inheritance tax and older farmers clinging on to their farms until they are wedi marw.

There are easy jokes to be made about an omerta and in the Sicilian town of Carmarthen. Speak ill of David Davies or stand up for the gassed badgers at the out-of-town mart on the St Clears Road and you’ll find yourself in the Towy with west Wales cement shoes.

The arguments of the farmers is leave us alone, we’re doing alright – we’re going to pass it onto our children; if we have to pay inheritance tax, we’ll have to sell the farm.

I’m assuming there’s no internal conflict of who among the chosen children inherit the family farm.

Caryl Lewis’s has written a good novel about this challenge in Martha, Jac a Sianco, set on the family farm in west Wales. It’s a dark rural romance.

Electric fences

The farmers on the mountain at March Hywel must have been tired of chasing us off their fields. They even put up electric fences. Admittedly these might have been for the cows but it was also a great game holding onto on to the wire as long as you dared before the volts charged through.

First one to let go lost. We once persuaded Gareth’s younger brother to stand over one fence with a leg either side. We laughed for days after that one.

During foot and mouth and then lock-down the countryside closed so quickly someone would have thought they didn’t really want hikers, ornithologists and dog walkers flattening the grass along the public footpaths.

There were cattle prods charged for miscreants.

I walk past my great grandfather’s farm this week. I can see the memories, hear the voices.

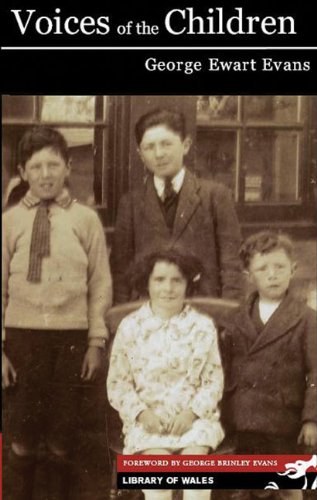

There’s a picture of my grandmother and her brothers as children on the cover of the Library of Wales edition of the Voices of the Children.

It was taken one summer in the 1920s. The picture is of old and worn now. The farm and the memories are fading into the land now, the walls crumbled and tight with blackberry and blackthorn.

I know some of the stories running through the stones.

They moved on.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Bit mean to your own ancestors.

Honest!