Raising a flag: Cynefin’s tender, brave and beautiful new album, Shimli

Stephen Price

Folk musician, Cynefin, has released his second album Shimli, a poetic, forceful and bar-raising work on the themes of language, agriculture and loss that was formed through conversations with elderly first-language Welsh speakers.

Shimli is the follow up to 2020’s critically acclaimed debut Dilyn Afon by west-Walian folk singer, researcher, grain grower and cultural historian Owen Shiers, aka ‘Cynefin’.

Continuing in the vein of rooting his music firmly in the customs and cultural vernacular of Ceredigion, the album takes its title from the now obsolete West Walian practice of all night musical and poetic vigils which used to take place in mills and workshops.

Drawing inspiration from folk song, the beirdd gwlad (folk poet) tradition – as well as living oral history and story, the album explores the intersection between music, poetry, food and the natural world.

A personal dispatch from the struggle to maintain a language, culture and way of life, Cynefin describes the album “a musical petition – a stake in the ground for the diverse and the disappearing in our age of homogenisation and mass amnesia.”

The album’s lead single Helmi presents the words of an obscure cân (a poem or song) by farmer Ifan Jones from Prengwyn.

In it, Evans describes the family farmhouse surrounded by a stoic army of helmi (corn stacks) in golden regalia, protecting the inhabitants from hunger and the scourge of winter.

As romantic as the depiction may seem, the piece is a poignant and lyrical account of the not-so-distant past. Not only have helmi disappeared from the Welsh landscape – significantly, so too have the native crops that once fed the nation.

For a country now almost completely reliant on imported food, there is perhaps a timely message in his words.

Pushing boundaries

To mark the release of Shimli on CD and streaming platforms, Nation.Cymru caught up with Cynefin to discuss the full length’s inspirations, his recording process, lost Welsh words, and his thoughts on the survival of Welsh language communities in west Wales.

Cynefin shared: “The inspiration for all the work I do, is very much garnered from where I live in Ceredigion.

“The first album I made was based on a folk song research project I did about six or seven years ago now, collecting and researching folk songs from Ceredigion.

“And so, in some ways, the second album has been a continuation of that, but it’s also branched out into other areas of Ceredigion’s cultural life, including the Beirdd Gwlad, the folk poet tradition, and stories and history that I’ve picked up along the way.

“I often go and interview old folk to find out what they know and glean what they know before they leave this mortal coil. So the sources of inspiration are much broader this time around.”

Shimli features a mixture of reworked and reinvigorated folk songs, poetry set to music composed by Shiers, as well as original songs.

Cynefin is a musician in the purest sense, enjoying the painstaking process of reshaping traditional folk music, with its existing words and melodies, then arranging them with a new lens which is at both turns rooted in the past and very much contemporary and of the now.

Other songs on the album take poetry to new places, allowing Shiers more creative freedom to use some of his favourite poems set to his own melodies.

He shared: “That was quite exciting to do for the first time. I’ve not really done much of that before.

“And then, with self-composition, there’s an awful lot of freedom, almost pushing the boundaries of what you might consider traditional, because there aren’t any limitations really when you’re self-penning.

“But I’ve tried to pay heed to that tradition in terms of using traditional verse styles, so that there’s some kind of traditional consistency to the album.”

Discussing the creation of the album, he said: “The album was recorded over quite a long period of time, really, in many places.

“One of the useful things about modern recording techniques is that you can take the sessions wherever you go.

“Some of it was actually done in London, some of it in the chapel down the road here, some of it at home, and all over the place, really. It’s so useful to have that kind of flexibility when you’re recording.

“It was produced by a chap called Lawrence Greed, who is an old family friend I’ve known for many years.

“He lives in London, but he’s done a lot with BBC Wales and worked with quite a few Welsh projects and has a strong connection with Wales. It was great to bring in his expertise on the album.”

Shimli

Setting the tone of the album is the title itself. An unfamiliar word to learners and many Welsh speakers alike.

Cynefin told Nation.Cymru: “Shimli, is a word which has passed out of common parlance now. It’s an old word which maybe only the people in their late eighties or nineties might remember.

“It came from the practice of milling oats. Farmers used to take their oats to the mill, and before de-hulling and milling the oat flour, they would have to pass the oats through a kiln overnight because there was a particular enzyme that gets disabled when you pass oats through a kiln.

“They would have to turn the oats every hour – it was quite a long process. So, they would invite their friends and neighbours around, and have a bit of a knees-up, drinks would get passed around, and then before long, somebody would share a poem or a story or a song.”

We would probably recognise it today in Wales as a sort of Noson Lawen, which still happens, though it’s become a lot more formal—now it happens on TV or in village halls—whereas this was far more natural and organic, the type of thing really that human beings have been doing for many years, or since time immemorial: just having a bit of fun, having a drink, singing, and sharing stories. That really spoke to me.

“I think it also encapsulates aspects of life that I wanted to focus on. The title Shimli really represents all the elements I was looking at, especially rural life aspects that have either disappeared or are on the verge of disappearing.”

Shimli aims to reflect the current age where everything is becoming homogenised, and we’re forgetting very quickly what came before and what makes parts of Wales unique and different.

“If we’re feeling lost in terms of where we’re going forward as a nation, I think we can do well to remember our past.

“So, the word Shimli really encapsulates a lot for me and sums up practices that sustained people in Wales—not just in terms of providing food and livelihood, but also as the real seedbeds, if you excuse the pun, for culture to emerge and be renewed.”

“Who are we?”

Cynefin lives in rural Ceredigion where the music scene has sprung to life both vigorously and organically over the past decade, and the whole world is starting to take notice.

He answered: “Well, I mean, folk music in Wales in general has been going through a bit of a revival.

“It’s in a much better place now than it was, say, 25 years ago. There’s been a real concerted effort, and perhaps it’s something which is being seen as cool.

“It sounds a bit strange, but it’s got to be seen as something young people want to do if it’s going to survive.

“So, perhaps it’s taken a few people doing something different with folk music for younger people to come along and think, “Oh, I could do that.”

He added: “There’s also perhaps a bit of a turning back towards our traditions when we’re asking, really, who are we in this new century that seems to be hurtling forward without any sort of let up.

“Ceredigion has a lot to offer, and I think it’s a really rich county, especially in southern Ceredigion, where Mari and I grew up about a few miles apart.

“It’s an area called the Smotyn Du, where Methodism didn’t really get much of a hold, so a lot of folk culture managed to cling on.

“There are plenty of sources of inspiration for folk artists who want to delve into that.”

Discussing his move from Wales, and then return after eight years, he shared: “I moved away for a while. I went to university in Bath for five years. I wasn’t actually studying for five years, but I lived in England for about eight years.

“I was 18, and immaturely I saw Wales as quite backwards and parochial, and I didn’t have much fun at school and just wanted to get out of there.

“But really, it took moving out of England and experiencing Wales from an outsider’s perspective that gave me an appreciation for what I’d been given growing up.

“It was perfectly normal for me to hear people speaking Welsh all the time, and suddenly that seemed like an exotic thing for people in England.

“I also had important formative musical experiences: I worked for Real World Studios for a bit with Peter Gabriel, worked with lots of world artists, including Seckou Keita. I encountered musicians playing their own indigenous folk music, which helped me reframe my upbringing and roots.

“It made me turn back to my roots in a way I never had before, and it gave me a new found appreciation for my background and made me think that maybe I could bring something to it.”

“Decay”

When asked about the future of communities such as those he grew up in, however, Cynefin’s answer might surprise those expecting a sugar-coated response. Like the truths in his music, he can’t help but be honest.

“Do I feel hopeful about Welsh language communities in West Wales?” he repeated.

“I don’t actually feel very hopeful because all I’ve seen in the last 25 years is decay.

“It might sound strange, given that I’ve just released an album, but I’m not sure how it comes across because I’m so close to it now, and I haven’t got much perspective.

“The village I grew up in has changed massively in the last 25-30 years, and it’s mainly dominated by retirees and people escaping the rat race.

“A lot of the old people have gone. A lot of the people who’ve been there for generations aren’t there anymore.

“It’s quite an alien place to me in some ways.”

“The census is showing that in Wales, decade after decade, the language is in decline. So, I don’t feel very hopeful.

“I think this ‘million speakers by 2050’ is a load of rubbish. Its use on a community level and in the home is decreasing all the time.

“That’s one reason I’m making the album—to try and raise a flag.”

And on the note of raising a flag, we asked about his plans to take Shimli on the road.

He told Nation.Cymru: “We’re on tour in March, at the end of February and start of March. We’re out as a four-piece—double bass, percussion, and another guitar, and I’m playing guitar and piano.

“We’ll be playing songs from the first album as well, but it’s really about giving people an opportunity to hear the music and hopefully enjoy it.

“I also tell the stories behind the songs to an audience. I do a lot of storytelling in between the songs and try to ensure English speakers, who don’t speak Welsh, are included in the landscape of the song, or can feel into what the song’s about, even if they don’t understand the words.

“That’s always really my aim with a live show. Lots of musical storytelling.”

The year is young, but if Shimli is a taste of things to come, Welsh folk music’s revival offers hope, and indeed seeds, for a Welsh language revival, despite any talk of decay and displacement.

This is masterful music which opens up with each and every listen, and proof that Wales’ culture and, indeed our language, is safe as long as it’s in the right hands, as long as we don’t turn away and run.

This is music that carries on legacies as old as the land itself – legacies that are as vibrant and vital today as they’ve ever been.

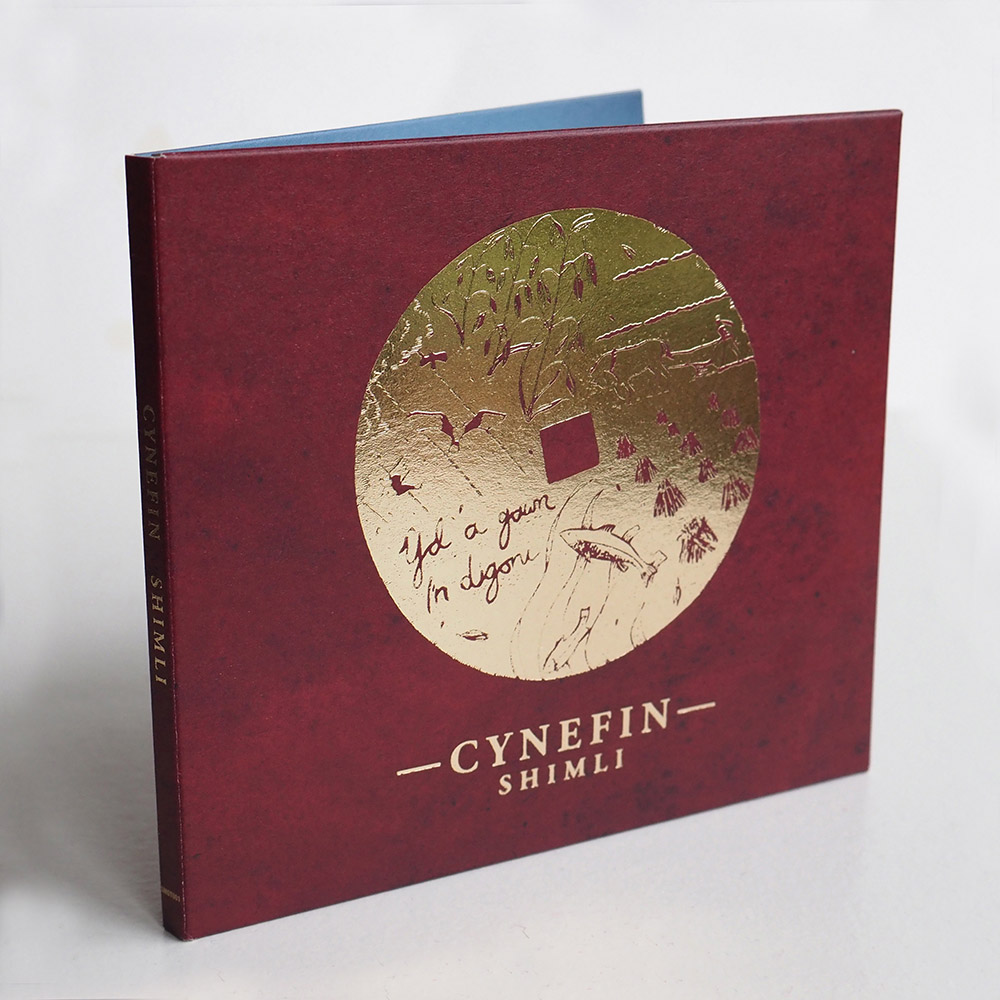

A must listen, and a must own, Shimli is available to purchase on CD, featuring further insight on the recording process set against exquisite imagery, and can also be downloaded or streamed online from your preferred platform.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

I’m proud to say I was a crowdfund supporter of Cynefin to enable Owen to get his first album made. There was a benefit; the Say Something in Welsh group were the biggest group of crowdfunders and we got a live concert in Caernarfon as a result!

Shimli is a thing of beauty, a truly beautiful set of songs. Listen on streaming platforms, but please support Cynefin by buying an real hard copy- CD or vinyl