Strikes and nasty landlords: The Welsh activist novel

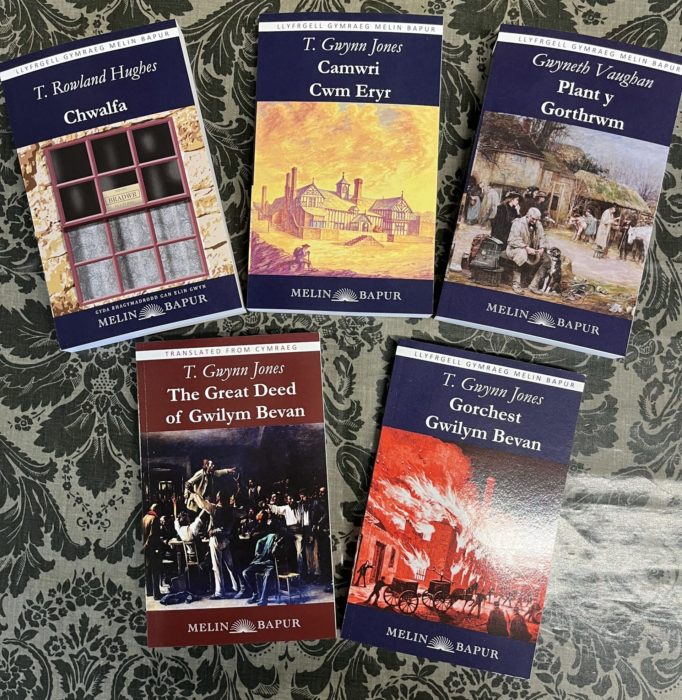

Adam Pearce Llyfrau Melin Bapur

It could be argued that the very act of writing a novel in Welsh is a political act – but our novelistic tradition has a strong track record of more overtly political statements going back to some of the very first novels published in Welsh.

By the end of the nineteenth century dozens of novels in Welsh were being published each year, but almost none of them will be familiar to readers today. T. Gwynn Jones’ novels are the most underappreciated of their age in Welsh, and like many of his other novels his second, Camwri Cwm Eryr (“The Cwm Eryr Injustice”; bonus points if you noticed the original title is a cynghanedd) completed in 1898, defies many of the stereotypes of the Victorian Welsh novel.

There are no ministers, no chapels, no spiritual navel-gazing, no hardworking Mams, though we do get a working-class hero in farmer Dafydd Owen. What we also get is an inheritance saga, crammed with unexpected twists, sensational revelations, and even a mining accident and arson case crammed in.

It would all make a great TV drama (over to you, S4C!), and like Gwynn’s other novels it would be a good place to start if you’ve never explored the literature of the period.

It is almost completely unknown, having only ever been published before now as a magazine serial, but a novel this fun certainly deserves rediscovery.

For all the expectations it defies, one element that is more characteristic of its period is the book’s antagonist and central character, the villainous Harold Jackson, and it is through him also that the novel lands its political blows.

Poetic

Jackson is an example of a character trope that was quite commonly employed at the time: the villainous English capitalist or landowner. Jackson is more of a cartoon character than a creation of real psychological depth, but his deterioration and eventual downfall provide the novel with its main narrative focus.

He also provides a source of poetic slapstick justice on several occasions, such as when, immediately after mistreating one of his workers, he falls from his horse and must ask the same worker’s wife for help (she refuses, with delight), and of course via his inevitable comeuppance at the end.

Tempting as it might be to read an element of ethnic prejudice into Jackson’s Englishness (which is in fact entirely incidental to the actual plot), the presence of numerous positive portraits of English people throughout Gwynn’s fiction belie this, even if his track record as a critic of all prejudices didn’t.

What’s really going on in Camwri Cwm Eryr is a kind of national wish-fulfilment; a ‘payback’ for the injustices Gwynn saw and experienced at the hands of the landed gentry.

In the absence of Welsh political institutions and the failure of the nationalist Cymru Fydd movement at the end of the 19th century, this was one of the only forms of resistance to cultural and class oppression available to the Welsh intellectual class.

A novel which does the same but is more explicit in its political message is Gwyneth Vaughan’s Plant y Gorthrwm (“Oppression’s Children”; 1905), taking as its subject matter the General Election of 1868 which, following an extension of the franchise, saw many Welsh tenant farmers—including, coincidentally, T. Gwynn Jones’ father—evicted by their landowners for voting against the landed gentry.

In contrast to Harold Jackson in Camwri Cwm Eryr, the landowner in Plant y Gorthrwm never even shows up and it is in fact his Welsh quisling minions in fact who carry out the injustices (with the suggestion that the landowner might not even be aware of what is being done in his name).

Curiously though, the ending of Plant y Gorthrwm actually arrives at a very similar place to Camwri Cwm Eryr. In both novels justice is restored when new faces take the place of the old at the top of the pile: in other words, by the replacement of ‘bad’ nobles with ‘good’ ones.

Of course this means our heroes get to live happily ever after with their vast fortunes, and that narrative justice is served; in both cases though the implication is that the ultimate cause of injustice is not the system itself, but merely the cruelty or ineptitude of bad actors within it.

When the upper classes are kind and just people, it’s implied, then all are happy. These may undoubtedly be activist novels, but they stop short of calling for revolution.

Industrial unrest

The best known of these realist political novels however are those which deal with industrial unrest. The most famous of all, T. Rowland Hughes’ masterpiece Chwalfa (“upheaval” or “chaos”) is also one of the last, looking back in many ways both in terms of its style—though written in 1946 it draws very much on the 19th century style—and subject matter, depicting the “Great Strike” in the Penrhyn quarry at Bethesda at the turn of the twentieth century.

Focusing on the impact of the strike on a single family through a series of loosely connected scenes, rather than closely following the characters’ journeys, the reader’s attention is always drawn back to the strike itself, the characters’ sense of powerlessness very much to the fore.

It is a novel of rare intensity and the criticisms that might otherwise be directed at it—its rather simplistic black and white morality, its stock, stereotypical characters and its romanticisation, even glorification of stoic suffering—fall away in the face of the novel’s sheer power and impact.

If you’ve even the slightest familiarity with the Welsh literary canon you will probably already have read this novel, but if not, what a treat you have waiting in store! There is a translation into English entitled Out of Their Night, but it may be hard to find.

A much earlier novel that tread similar ground but in a very different way was the one T. Gwynn Jones wrote immediately after Camwri Cwm Eryr. Like Chwalfa, Gorchest Gwilym Bevan (written in 1899; an English translation was published this year entitled The Great Deed of Gwilym Bevan) also deals with a strike in a north Wales quarry, but this the focus is more personal than social as we follow the effects of industrial unrest on the title character’s struggle with social acceptance, his mental health, and agnosticism.

Whilst the novel’s general perspective is romantic-heroic, having being written immediately before the Great Strike (coupled perhaps with a greater degree of detachment from Quarry culture on the part of the author) means the novel avoids Chwalfa’s simplistic moral compass, and shows the striking workers become desperate and violent rather than suffering in silence.

Comparing these two “strike in a Quarry” novels would make a fantastic Masters’ thesis!

All the novels mentioned above are available from www.melinbapur.cymru, with Camwri Cwm Eryr newly released this week and priced at £11.99; and Chwalfa and Plant y Gorthrwm available at the same price.

Gorchest Gwilym Bevan is available for just £8.99 and its English translation The Great Deed of Gwilym Bevan at £9.99. Melin Bapur’s books are available from a range of bricks-and-mortar bookshops across Wales, and as eBooks from all common eBook providers.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.