The Gannets of Grassholm, Part 5: The Massacre Becomes a Cause Célèbre

Howell Harris

How and why did the slaughter of a few dozen seabirds and the taking or smashing of a couple of hundred eggs on a remote Welsh island turn into regional and then national news, leading quickly to judicial investigation, questions in Parliament, and even a half-hearted government response?

Because the Army officers and gentlemen who did it chose the wrong witnesses for their bit of Whit Monday sport, which was a crime.

The killing, injuring, or taking of seabirds during the nesting season, though not the collecting or destruction of their eggs, had been illegal since 1869.

One of the Naturalists, probably Joshua Neale, wrote to the editor of the South Wales Daily News demanding that “Surely there must be some redress against such ruffianism however well-dressed the perpetrators.”

Thomas Henry Thomas himself thought “they must be followed by the bitterest contempt of every true sportsman and naturalist.”

The difference between them was that Thomas knew how to turn their anger into an aroused, influential public opinion.

In later correspondence between the two of them about the conservation of Grassholm’s gannets, he referred to Neale as the island’s “Pirate King.” But he was the Major-General.

Justice

Thomas was in an ideal position to mount a publicity campaign because he was, among many other things, the Cardiff correspondent of a new illustrated national newspaper, The Daily Graphic, whose weekly predecessor, The Graphic, he had supplied with illustrations for years.

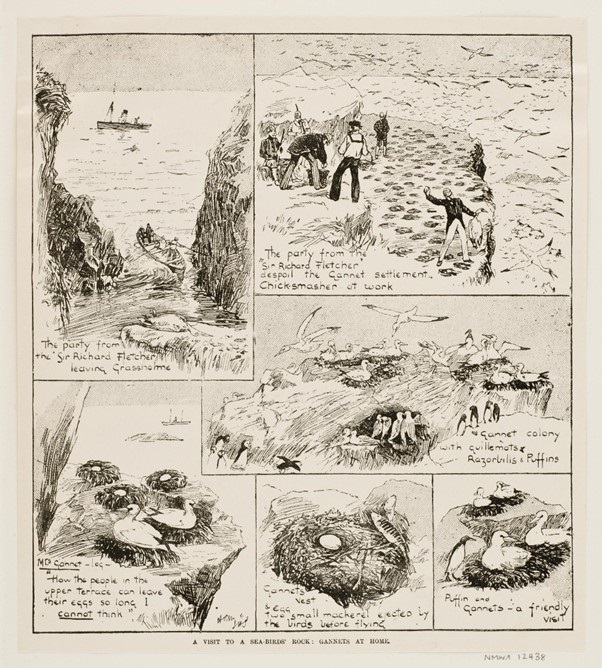

When Thomas got back to his studio from Grassholm he turned his recent shocking experience into an illustrated story that the Daily Graphic published just days after the event.

Strong words were accompanied by strong images – his island sketches were translated into engravings and assembled into a sort of horror cartoon.

First the innocence, then the slaughter.

His aim was clear: to stir up a fuss.

“[A]s I, powerless to prevent the destruction, sketched their doings, I ‘chortled in my joy’ to think that, with the aid of the Daily Graphic, justice will be done upon these poachers.” As, eventually, it was; after a fashion, at least.

Wide Circulation

Thomas’s report in the Graphic received immediate and wide circulation. The South Wales papers, in particular, reprinted it almost verbatim, and even without the above illustration it had the power to shock.

Publicity led very swiftly to inquiry, debate, condemnation, investigation, and eventually prosecution.

Within a couple of days the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals was on the case, and the hugely respected stipendiary magistrate for Swansea, John Coke Fowler, began his own inquiries, even though the incident had not happened in his district.

Fowler’s son William was a celebrated ornithologist and nature-writer, and he was evidently a bird-lover himself: “the shocking attack on the lives, nests, and eggs of our beautiful sea-birds … must excite extreme indignation. The admirers and lovers of birds must shudder at the story of this unlawful, cruel, and cowardly invasion of the homes of the gannet and the puffin.”

‘Exaggerated’

His investigation rapidly bore fruit. He got in touch with Rear-Admiral Richard Mayne, the Tory MP for Pembroke, who obtained for him a copy of the written statement that the officer in charge of the Sir Richard Fletcher, who was not identified by name, had produced for his superiors.

This officer admitted the offence, while claiming that Thomas’s account was “much exaggerated,” and that he and his colleagues believed that Grassholm was outside the protection of the 1880 Wild Birds Preservation Act, which had incorporated, widened, and strengthened the original 1869 law only covering sea birds.

This was something Coke Fowler rightly doubted.

Questions

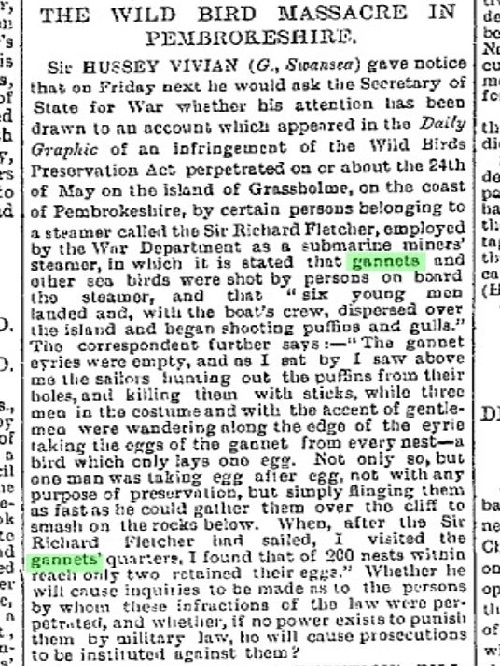

Within days MPs were asking questions of Ministers, in conversation and letters and then on the floor of Parliament.

Swansea District’s Sir Henry Vivian, a leading local industrialist and a Liberal like his neighbour and colleague Lewis Dillwyn, sponsor of the 1880 Act, was the most pressing critic, possibly benefitting from the advice of Dillwyn and Coke Fowler and certainly pursuing the same agenda.

So, quite understandably, the Conservative junior minister tasked with dealing with his questions chose instead to answer an easier one from Robert Webster, Conservative MP for St. Pancras East.

Webster was acting in response to information he had received from the Bath branch of the Selborne Society, a conservation organization.

His purpose was to get confirmation that the 1880 Act did apply, and an undertaking that the government would “take steps to prevent the repetition of such acts by persons using Her Majesty’s ships.”

Anodyne answer

The ministerial response was to serve up a suitably anodyne answer going no further than what the anonymous officer had already admitted.

Thomas’s report was true but exaggerated, “an officer [i.e. not a group] of the Royal Engineers [no mention of other units] did land on Grassholme (sic), which is an isolated rock far out at sea [i.e. not even a proper island], and did shoot some sea birds [i.e. no mention of their even worse conduct] under the mistaken idea that the Wild Birds Preservation Act did not extend to the spot” [emphases added].

The intent of the statement was to try to minimise the significance of everything that had happened, and to sweeten the pill by including a weak guarantee that nothing similar would happen again.

The Commander-in-Chief [Queen Victoria’s aged uncle HRH the Duke of Cambridge, who was also the president of a branch of the Selborne Society] had expressed his disapproval and given orders to prevent any repetition.

There was no mention of prosecution as one of the ways the law provided for this exact deterrent purpose.

Dissatisfied

If the Army and the government thought that this very limited response might be enough to calm things down, they had another think coming.

The following day Vivian was back on his feet, asking his question of the Secretary of State for War in person, having been dissatisfied with his junior minister’s answer.

He still wanted “inquiries to be made as to the persons by whom these infractions of the law were perpetrated; and whether, if no power exists to punish them by military law, he will cause prosecutions to be instituted against them.”

The Secretary of State stood fast: “There is no intention on the part of Her Majesty’s Government to prosecute any persons in respect of what has been done.”

He claimed not to know who the perpetrators were, which cannot have been the whole truth unless his ignorance was the result of a deliberate lack of curiosity; Vivian asked him to find out.

He did not agree to do so, merely to consider it – which turned out to mean, unsurprisingly, a polite No.

Unimpressed

The RSPCA was unimpressed. The Secretary’s answer was “even less satisfactory” than his Minister’s, “as it showed a disposition to hush up the matter.”

“The War Office appeared to have closed the avenues of information.”

The Bath branch of the Selborne Society was unimpressed too: “The names of the persons … were known to the authorities, but they steadfastly refused to divulge them, and thus threw over the offenders the official aegis.”

They ought to be prosecuted and punished — “a measure they richly deserved.” As for their “absurd” excuse, “the wanton destruction of wild birds, like petty larceny and other wicked deeds, is not considered wrong because it has been made illegal, but it has been made illegal because it is considered wrong.”

Contempt

The Queen magazine was similarly unconvinced: their excuse was not “worthy of such noble sportsmen and honourable gentlemen,” it stated, in an excoriating editorial dripping with ironic contempt.

Men “claiming to be regarded as officers and gentlemen” had demonstrated their “contemptible folly,” and the Secretary of War had handled the affair poorly too.

“[W]ithholding the names of the offenders, and so screening them from the punishment due…, is unseemly, to say the least, on the part of a Minister, giving rise to an opinion that some pressure has been brought to bear in order to screen some influential person.”

The fact that the RSPCA, a conservation society, and the editors of what called itself “The Lady’s Newspaper” were on the same page about the nature of the crimes of the Sir Richard Fletcher’s officers, and the punishment they should receive, may seem surprising.

But what it pointed to was the breadth of public opinion hostile to animal cruelty and in favour of the protection of birds, which meant that the campaign Thomas Thomas had kicked off resonated widely and powerfully.

I will explore this more deeply next week.

Damning

The Army officers had crossed a line which meant that they could no longer even depend on the loyalty of their own class.

The Army and Navy Gazette, for example, weighed in against them for the “particularly scandalous and inhuman manner” of their crimes, outraged that the public might mistake them for “Bluejackets” (sailors) and assume that their “ridiculously named” ship belonged to “the Queen’s Sea Service.”

So too did the editor of The Field, “The Country Gentleman’s Newspaper,” dedicated to the traditional outdoor pursuits but also to the newer hobby of observing, understanding, appreciating, and collecting flora, fauna, and anything else that took their fancy.

It printed a damning letter about the affair and added that “We have no doubt that many of our readers will endorse this protest… We are at a loss to understand why the law is not enforced in districts where such wanton and wholesale destruction is effected. … a prosecution would, we feel sure, be viewed with satisfaction by many of our readers.”

Gruesome

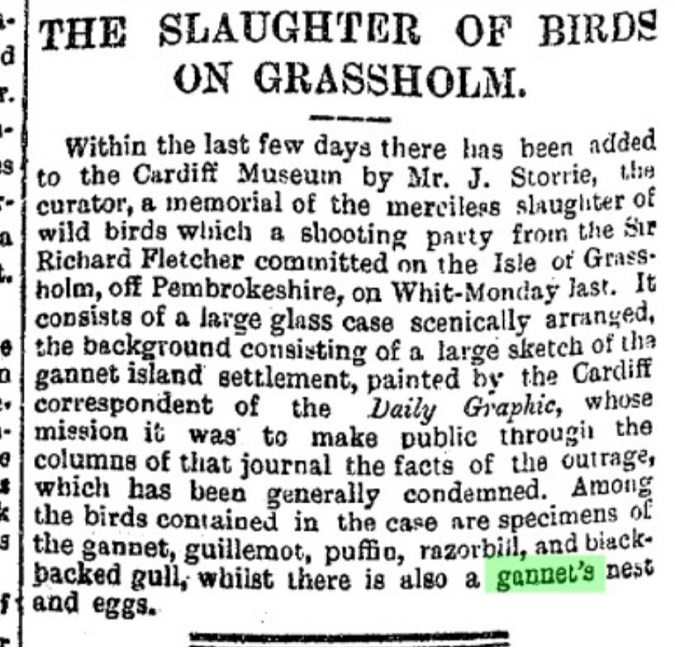

The officers of the Sir Richard Fletcher might already have been convicted in the court of public opinion, but this was not enough for their critics. The RSPCA kept up the pressure, and so did the Cardiff Naturalists.

The centrepiece of the Naturalists’ campaign was a gruesome new exhibit in the Cardiff Museum, of stuffed birds taken from the piles of dead on Grassholm and prominently displayed in an enormous diorama case as a “memorial of the merciless slaughter.”

The oil painting reproduced in Part 4 of this series formed the background.

The dominant feature was the gannet seen lying dead on a rock in Thomas’s final sketch, of the “marauders” leaving the island, which occupies the top left of his horror cartoon.

As he had written in the Daily Graphic, he “sincerely wish(ed)” that he could have hung it around the neck of the officer who killed it, “like that of the fateful albatross” in Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner.

Thomas Thomas must have been happy with this artistic display, which was as close as he could get to carrying out his wish.

He included himself in this engraving of it that he published in the pamphlet he wrote about the affair.

Read the previous installments of the Gannets of Grassholm here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.