The Gannets of Grassholm, Part 7: Officers and Gentlemen – the perpetrators revealed

Howell Harris

It is time to make the acquaintance of our other principal characters, the officers who committed the crimes and the enlisted men who rowed them from the Sir Richard Fletcher to the island and back.

The officers’ identity matters. The RSPCA thought they had committed “the most wanton violation of the law for the protection of birds” that had occurred since the passage of the Wild Birds Preservation Act in 1880 not simply because of what they did, or how many birds they killed, but because of who they were.

The Sunderland and South Shields day-trippers had shot far more birds on the Farnes on August Bank Holiday 1887. But they were not proper gentlemen. The officers certainly were. They ought to have known better.

As the South Wales Daily News editorialised, the Grassholm slaughter was such a great outrage because of its nature, its impact, and the people who did it.

They were “marauders” who had “committed an act of the most meaningless cruelty,” whose consequences for the survival of the gannetry meant that “Even those who are not naturalists will understand … the gravity of the offence.”

“We suppose that her MAJESTY’s marine servants are bound to render obedience to the laws of the land, and we hope they will be made to understand this.”

One of the Cardiff Naturalists, probably Joshua Neale, wrote to the same paper to emphasise that “This was done by the leaders of the party who, from their bearing, seemed to be officers. … To compare the doings of this shooting party, with those of ‘Arry and his friends out for a ‘oliday [men like the Farne Islands killers, for example] would be to do that well-known character a grave injustice.”

So in this case the officers’ profession and class background compounded their crime rather than offering them the usual relative impunity.

The culprits

The shooting and nest-raiding party included Lieutenant-Colonel Morgan James Saurin JP, Captains Herbert de Haga Haig and William Lueg Harvey, and Lieutenants Caulfield, Dickson, Molesworth, and Shakerley.

The boat crew, not so directly responsible for the slaughter, were Sergeant-Major John Cunningham, Corporal George Davis, and two Sappers, William Lee and George John — referred to in some accounts as Captain John, because he actually piloted the ship. But in the Royal Engineers skilled manual work was a squaddie’s job, not an officer’s; his job title was “coxswain”.

There was also an eighth bird killer who was never publicly identified or charged and never appeared in court, except on the bench.

As Captain Haig told the RSPCA Inspector who interviewed him, “I must not divulge his name. He has asked me not to do this, and I must not therefore do so without his permission. He is a member of the County Council and a magistrate, and it would be well if the case could be heard by him” (italics in original). Strangely, the Inspector did not press him on this sensitive and significant matter.

Saurin

Morgan Saurin (45) began his military career as an officer (by purchase) in the Dragoon Guards and since 1878 had served as the popular and efficient Lieutenant-Colonel, i.e. commanding officer, of the Pembrokeshire Yeomanry. He was often referred to as Colonel, but this was just an honorary title, conveyed in 1886.

He was thus a key figure in county society. Young men of most of the leading families served with the Yeomanry, a cavalry regiment whose battle honours included victory over the French at the Battle of Fishguard, 1797, the last invasion of the British Isles. The Yeomanry was rather like the Pembrokeshire Hunt, but in a different uniform.

Saurin was the lord of the Manor of Orielton south-west of Pembroke – ironically, much later the home of Ronald Lockley, after his years on Skokholm had ended, and then (until last year) a Field Studies Centre.

He was the product of a marriage between a father from an Anglo-Irish family and a mother from the Joneses of Cilwendeg in North Pembrokeshire, another of the finest Georgian houses in the county.

Saurin was a magistrate, and had been high sheriff, for Pembroke, a county councillor, a pillar of the local Tory party, and an active supporter of the incumbent MP, Admiral Mayne.

He was also an enthusiastic hunter to hounds and wildfowler. His landholdings (c. 6,000 acres) extended as far as Pennar, near Pembroke Dock, which meant that he was a neighbour of the Submarine Miners, whose depot was at Pennar Point, as well as the highest-ranking Army officer in the county.

A man like Saurin, sporting and sociable, must have been an important patron for younger regular officers rotating for a few months to a couple of years at a time through an isolated posting like Pembroke Dock, and a valued source of recreation and hospitality.

The expedition to Grassholm was perhaps a way for them to reciprocate.

Clan Haig

Herbert de Haga Haig (35) was a member of a junior branch of the ancient Scots border family the Haigs of Bemersyde, hereditary chieftains of Clan Haig, and the youngest of three sons.

Born in Ireland, he was brought up in London, and attended Kings College School until he joined the Royal Engineers in 1873.

The family’s most celebrated member later in their lives was his younger cousin Douglas, eventually promoted to Field Marshall and given an Earldom for his leadership of the British Army in World War I.

Herbert’s career was far less distinguished but extended over more than thirty years and several continents. It started well: after service in Mauritius, about whose physical features and geology he produced a monograph, he was sent to the Army Staff College in 1881 and passed, one of just two out of 35 Lieutenants in his Engineer cohort to achieve this distinction.

He only saw one period of active combat; his older brother Percy, a military surgeon in the Indian Army, had far more. When he was with the Submarine Mining Service at Halifax, Nova Scotia in 1885 he volunteered to join the expedition to suppress a First Nations rebellion in Canada’s North-West Territories, now Saskatchewan. It brought him a Mention in Despatches.

Haig was a brave officer, “most energetic and willing” according to his commander on that expedition, and a very capable engineer.

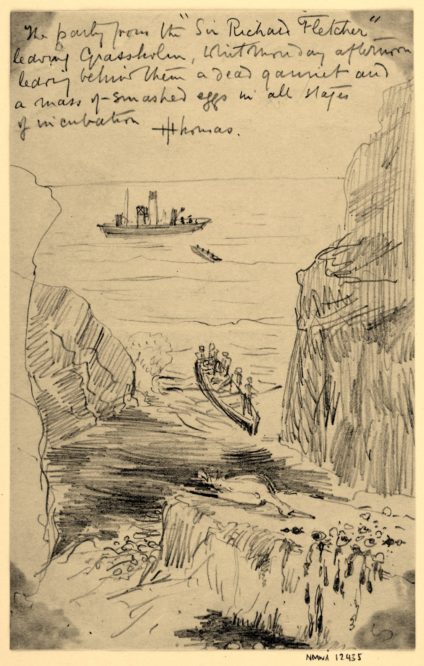

He was responsible for the effective improvised defences that helped to decide the crucial Battle of Batoche. He was also an accomplished amateur journalist and artist, sending his reports and sketches of the war to the Illustrated London News, which described him as their “military correspondent”.

Impolitic criticisms

Once the fighting finished Haig was sent back east by his commanding officer, probably because he was accused of making impolitic criticisms of the expeditionary force and its operations.

He then enjoyed a spell in Bermuda, where he met Theodore Roosevelt and they became friends, going shooting together. Roosevelt, who called him an “educated and traveled Englishman”, exchanged letters with him for years.

Then in 1886 he brought his company back to England and, after spells at Chatham and Harwich, was appointed Adjutant of the Southern Submarine Miners Militia, based in Gosport, in 1887. In May 1889 he returned to a regular company, so he had been a year in post at Pembroke Dock by the time of the Grassholm Massacre.

Captain William Lueg Harvey (32) was born in Hayle, Cornwall and was a member of a leading family of engineers and ironfounders. He joined the local regiment, the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry, whose Second Battalion served alongside artillerymen with the Pembroke Dock garrison force in 1890.

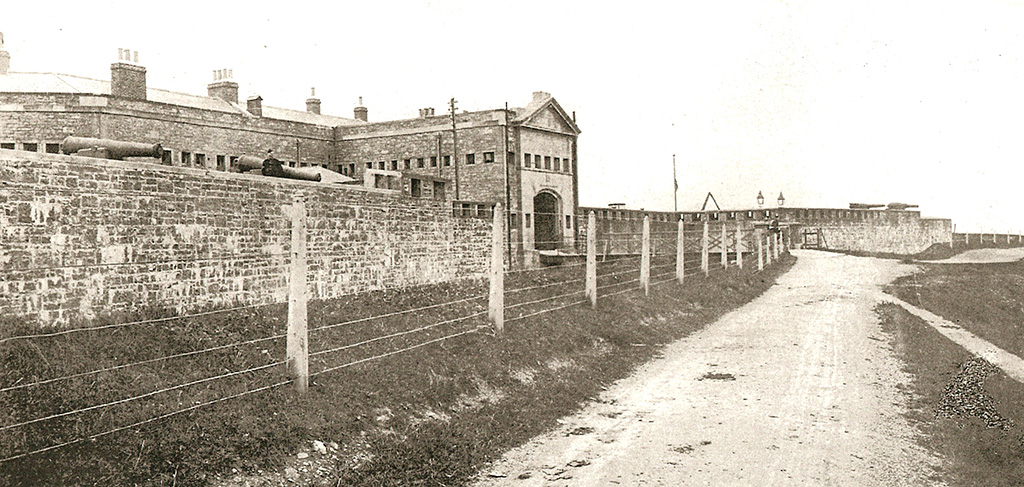

The Submarine Miners’ depot lacked living quarters, so they mucked in with other soldiers in the town’s decrepit Defensible Barracks or newer but equally depressing buildings known simply as The Huts.

Their few officers (a Major, two Captains, and two Lieutenants) messed with their fellows too.

Like Haig’s, Harvey’s career alternated home and overseas postings. He served in Egypt in 1882, where he fought at the battle of Tel-el-Kebir, and in the Sudan Expedition of 1884-5, in both of which campaigns he picked up medals, and later went to South Africa for the Boer War, where he was awarded a DSO for showing exemplary conduct in combat.

The young Lieutenants have left much less of a trace in the historical record. Two of them were Engineers, two DCLI.

St. George Robert Sanderson Caulfeild (22) had been a 2nd Lieutenant since 1887 and went on to enjoy a long career in the R.E., ending up as a Lieutenant-Colonel. Despite what one might suppose from the year of his death (1916), he died not on active service but on a golf course in Leeds.

Richard Travers Dixon (25), an Old Harrovian, had been a 1st Lieutenant since 1885. He did not stay long in the Engineers, and his main distinction would be an Olympic Gold Medal for yachting in 1908.

The Hon. George Bagot Molesworth (23), educated at Wellington College, was a 2nd Lieutenant in the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry, and the heir to two fine-sounding Irish titles – Viscount of Swords and Baron of Philipstown – which did not, however, entitle him to an eventual seat in the Lords. His military career would be quite long and undistinguished, peaking at Major in the Army Pay Department.

Ernest Alfred Shakerley (24), like Captain Harvey, would serve with some distinction in the Boer War, where he was mentioned in despatches; he ended up as a Major too. In May 1890 he had only just (Friday 23rd) received his first promotion, to Lieutenant, when he joined the fateful shooting party. Perhaps he was celebrating.

Finally, Major Francis Quintin Edmondes (48), from an old Vale of Glamorgan gentry family, was the senior R.E. officer in Pembroke Dock.

He was not on board the Sir Richard Fletcher on the trip to Grassholm, but he had authorised Haig to take her out so would eventually find himself in court alongside members of the shooting party on a charge of aiding and abetting them.

“Stupid, unthinking men”

One reason for putting together these sketches of the careers of what the South Wales Daily News called these “stupid, unthinking men in H.M. service” is to reach a conclusion that most of them, and particularly Captain Haig, were probably neither especially stupid nor even unthinking.

The Radical weekly Reynold’s News might editorialise that their conduct was “disgraceful evidence of the coarse and brutal fibre of which these officers are made,” but all this really meant was that it disapproved of their behaviour in this instance and assumed that it demonstrated they were rotten to the core.

But Royal Engineers officers, in particular, had to be technically proficient and capable of absorbing tough professional training. Within the R.E., the Submarine Mining Service was particularly demanding. It was relatively recent, organized in the 1870s to use the new technology of tethered mines so effectively deployed by the Confederacy in the American Civil War.

Officers had to be intelligent and well educated to be able to understand and use the complex, dangerous devices they deployed. They were skilled in electrical and mechanical engineering as well as the R.E. officer’s core skills of surveying and construction.

They worked in small, isolated detachments (about 60 in the 35th Company at Pembroke Dock) scattered around the British coasts and across the Empire, liaising and cooperating with other units – the Royal Artillery manning coastal guns and the Naval authorities in the ports they were tasked to defend – in complicated combined operations.

Anomaly

Personnel might not stay very long in any particular port, but to ease problems of recruitment and to supply local knowledge regular soldiers were supplemented by part-time volunteers as well as by civilians.

These were, mostly recruited from the local maritime community, like the members of the Milford Haven Militia unit, raised in 1889.

Submarine mining was unglamorous, tedious, but demanding work, defending ports against supposed threats, mostly from the French and the Russians, that never materialised.

The Submarine Mining Service was an anomaly – as a contemporary critic put it, “a naval force owning (sic) no allegiance to, and submitting to no control from, the Admiralty.” But it was quite a large anomaly.

When it was disbanded in 1904, it had almost 6,000 personnel, about a third of them regulars.

Next week we will meet these men again – under investigation, and in court.

Read the previous installments of the Gannets of Grassholm here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.