The Gannets of Grassholm, Part 8: Investigation, Trial – and Punishment?

After the perpetrators of the Grassholm gannet massacre of 1890 were identified as ‘officers and gentlemen’ and possibly even a magistrate, the ensuing court case ruffled legal and media feathers across the board, the story continues as these men go to trial.

Howell Harris

The weakness in the government’s strategy of stonewalling public demands for action was that the RSPCA had the power to bring private prosecutions and was quite prepared to do so .

Its annual national budget was about £22,000 (c. £12,000,000 nowadays), plus more in its branches, most of it spent on the Society’s “chief work”, policing, prosecuting, and otherwise discouraging cruelty to animals.

Its officers had an unparalleled knowledge of the relevant law, and a high success rate in court.

The two Inspectors on the case, both former policemen, had the eyewitness testimony of the Cardiff Naturalists about what had happened.

Then they started asking questions and through “perseverance and skill” obtained the names of some of the offenders, who they pursued.

Captain Haig was their first and most helpful interviewee, perhaps because he had little to lose or to fear: even before the trial it was reported that he had been severely reprimanded by the War Office.

“It appears that the cruise of the Sir Robert (sic) Fletcher on this occasion is not regarded as part of the duties appertaining to the training of the submarine miners, and in consequence the authorities waxed wroth — not over the massacre of the innocents, but over the consumption of Government stores.”

Responsibility

When he met Inspector Tregaskis in London, Haig explained himself quite fully as well as supplying or confirming the names of all but one of the other participants, “[a]fter a good deal of hesitation and some objections.”

The purpose of the trip had indeed been “to shoot seabirds” and “to fire for fish; and for regular service” (an attempt to argue that he had not simply taken his ship out on a jolly, it was also an exercise).

His fellow-officers had all been his invited guests. He “took all the responsibility” and was “in full command,” though he also attempted to get himself partly off the hook or at least implicate his commanding officer: “I got permission of Major Edmunds (sic) to use the boat for that purpose,” which was not what the Major would later claim.

They had taken guns with them, and had indeed shot and taken birds, “which we wanted as specimens” to add to taxidermy or skin collections.

They also took eggs, but he claimed there was no mindless smashing – they checked the eggs in water, and only broke those that were no good (by which he probably meant too developed to be fit to eat or blow for egg collectors).

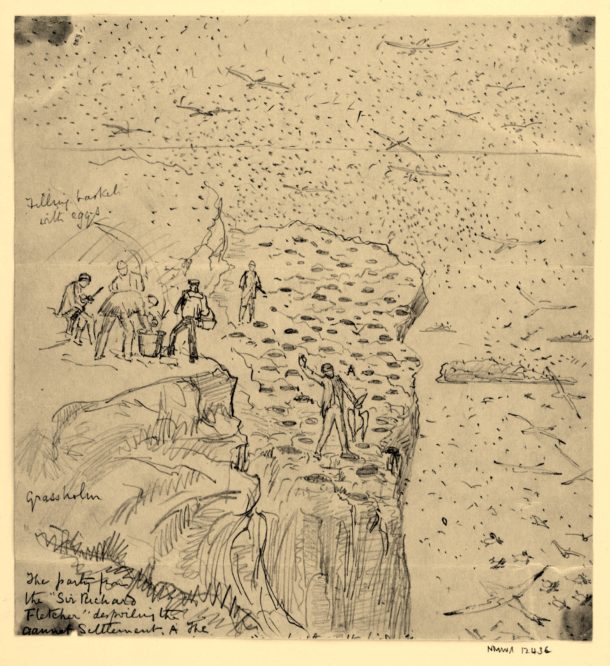

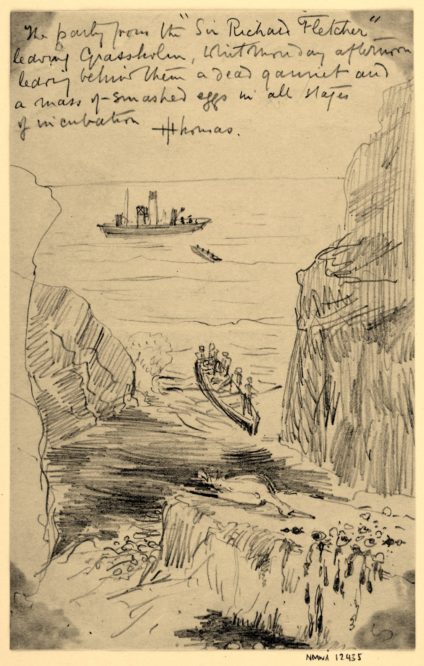

However, Thomas Thomas’s drawing includes no bucket for this testing, and when he went over the scene of the crime after the culprits had left there were smashed eggs “in every stage of incubation.” So Haig was probably lying.

Duck decoy

Saurin was equally forthcoming when he and Tregaskis met at the Naval and Military Club later the same day.

“I had never been to the Island before, and I was most anxious to go and kill a few birds.” (Sergeant-Major Cunningham said he had been “the most eager in shooting”.)

“They say you are a good shot, Colonel, and killed many birds on your way to the island,” Tregaskis probed, flatteringly.

“No, I think not,” replied Saurin, either disingenuously or perhaps modestly. “[O]f course I tried, but I was the worst shot on board. We killed several, but when we got on the Island, I used a stick to kill the birds with, for I think it was better sport and fun to do so, as the birds were very thick about, and I got at them on coming off their nests.”

This admission might surprise us, but Saurin had years of experience killing thousands of wildfowl with a stick or his bare hands on his Duck Decoy. He saw nothing wrong with it; it was even enjoyable .

Puffins

The other officers, interviewed back in Pembrokeshire by Frederick Clarke, lately a very energetic local policeman, were somewhat less helpful and more defensive.

Captain Harvey was quite straightforward. He went because “I wanted some eggs and puffins, as specimens.” He shot two and took them back to base, satisfied.

Lieutenant Dixon emphasised that he was there at Haig’s invitation, i.e. it was not his idea, and he only fired at one gull.

Molesworth said the same but admitted that “We shot at puffins from the boat on our way there whenever we had a chance. I did not know that they were protected.”

“I cannot say positively that we were invited [by Haig] to shoot birds; but we took the rifles for that purpose, of course.”

Shakersley had a more imaginative excuse than mere ignorance: “I thought puffins were not protected. They are destructive to rabbits.”

Caulfield was the least responsive: “Well, I was there; but I cannot see what you want to make a bother about [it] for. I shall say no more.”

As for Major Edmondes, he was completely affronted to be asked if he had given Haig permission by a civilian, albeit a former policeman: “I don’t see what that has got to do with you or with the case. I shall not tell you whether I gave permission or not. It is a great piece of impudence on the part of the Society to interfere in this matter.”

Misdeeds

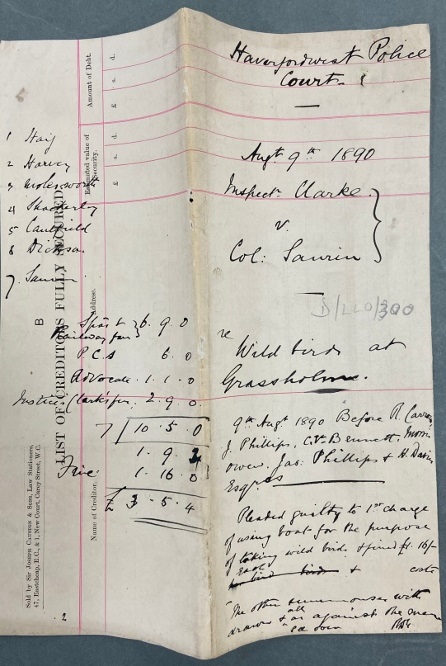

So the RSPCA built its case and, though the local law-enforcement authorities were no more prepared to prosecute than the government had been, it was strong enough to be taken before the Haverfordwest magistrates anyway.

It was a most unusual case for them. Pembrokeshire was a low-crime area.

The police and magistrates’ everyday business was just coming down hard on the everyday misdeeds of the lower orders.

Court registers were full of drunkards, bastardy cases, workhouse residents refusing to pick oakum, parents not making sure their children went to school, etc. Now they had to deal with an actual crime committed by their own peers.

Coverage

The trial was widely covered. The RSPCA was represented by the barrister son of its influential secretary John Colam.

He had prosecuted the Sunderland and South Shields bird-killers three years earlier and came down from London for this one too, which indicated the importance they attached to it.

It was, he emphasised, “a most expensive [case] for the Society.”

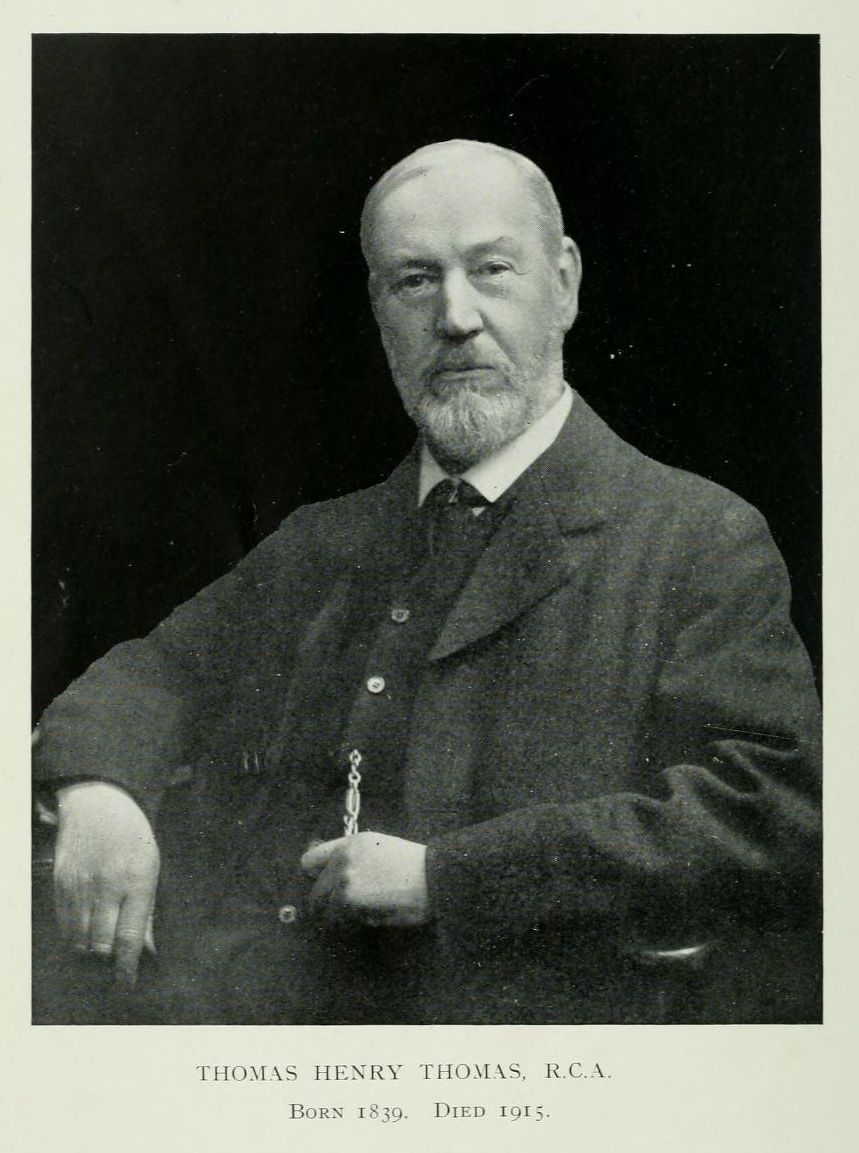

Joshua Neale, Thomas Proger, and Thomas Thomas travelled from Cardiff to give evidence, but in the event none was called.

There was no testimony because as soon as Robert Colam had made his opening statement outlining the charges and the evidence he would submit, the defence lawyers suggested a discussion with him rather than proceeding to a full trial.

Plea bargain

The outcome was a plea bargain. Six initial counts were reduced to the one for which the evidence was rock-solid and indisputable, using a boat for the purpose of shooting or causing to be shot 25 wild birds – far fewer than their actual haul – and guilty pleas from seven of the original dozen defendants were accepted.

The dropped charges were all against named individuals: Lieut. Dixon and Captains Haig and Harvey, for shooting wild birds; Colonel Saurin, for killing them with his stick; Corporal Davies and Sapper Lee, for “being in possession of a puffin”; and Major Edmondes, for providing the others with the Sir Richard Fletcher by allowing Haig to take her out on the hunting trip in the first place.

Collection or destruction of eggs, even in the nesting season, was not a crime under the 1880 statute, so much of the public anger against the Army officers’ conduct could not even hope for any satisfaction, given the law as it stood.

All charges against the NCOs and soldiers who had rowed the hunting party ashore and perhaps participated in the slaughter too were dropped on the grounds that they were simply “private soldiers acting on the occasion as servants and under instruction.”

This was an interesting inversion of usual practice in animal cruelty cases, in which employees (coach drivers, farm labourers etc.) were more frequently the targets than the employers who presumably directed them or at least authorised their conduct.

Perhaps this was a recognition of the force of military discipline, or maybe it was simply a convenient way of justifying dropping the charges against the small fry as the officers and gentlemen were not attempting to flee the net.

Escaped Justice

All except Major Edmondes, who escaped justice simply by stating, contrary to Haig’s statement, that he had no idea what his colleagues planned to do.

As Robert Colam had no direct evidence to the contrary, he agreed to drop the charge of aiding and abetting against him.

This did not satisfy Edmondes, who protested that he ought never to have been charged at all, and the case against him ought to be dismissed with a costs order in his favour.

“He had duties to perform, and he had been called before the court unnecessarily, and the time of the court had so far as he was concerned been wasted.”

Colam stood his ground: had the case gone to a full trial, he said, the statement of one of the accused (presumably Haig) would have justified the charge.

That left just Colonel Saurin, Captains Haig and Harvey, and the four young Lieutenants, who did not contest the RSPCA’s statement of facts and accepted their guilt.

Public record

Their lawyers then argued that it was not necessary to protract the hearing any further.

But Colam insisted on making a long and detailed statement to get matters into the public record, using the argument that the magistrates needed to know the details before proceeding to sentence – as if anybody in their position would not know the facts already, given the publicity the incident had received and their close personal acquaintance with some of the accused.

The defence lawyers thought this was very bad form – trying “to drive the case home with unnecessary severity” – but Colam would not be silenced, making it clear that his right to make a statement was a condition of his acceptance of the plea bargain.

“The object of the prosecution was not to inflict any penalty upon the gentlemen who were charged, but in order to bring the statute forcibly before the minds of the public and to prevent a repetition of the acts that were done on this occasion.” However, a sufficient penalty was an essential part of the object lesson he wished the prosecution to teach:

If this had been a case in which a gentleman had been walking along a road and seeing a gannet or other bird rise, had used his stick and struck the bird down on the spur of the moment…, it might have been termed an involuntary act, and one that could very well have been passed over by a fine of 6d and costs. … But when people borrowed a boat and, taking a gun with them went to an island where birds were gathered together so thickly that it was only necessary to walk along and with the aid of a stick produce terrible havoc, then the case was totally different.

So he argued against a purely nominal fine and in favour of one that would serve as a deterrent to future offenders, “having regard to the character of the defendants, and their presumed knowledge of the law”:

When officers of the army went deliberately out armed with guns, indiscriminately slew wild birds, and as Col. Saurin said, ‘There was no need to use a gun, as it was better sport to hit them with a stick by walking along’ – when officers in her Majesty’s army acted in this way it was a matter that required to be dealt with with a firm hand.

Ignorance

The defence lawyers counter-argued that a mere costs order, accompanied by a dismissal of the charges or a reprimand, would suffice, on the grounds that their clients had admitted their guilt, that it was a first offence, and that they claimed complete ignorance of the law – rather different from their original argument that they did not think that it applied on Grassholm.

The claim of ignorance was not tested by questioning, but it does not seem very plausible; the RSPCA dismissed it as “untenable.”

Colonel Saurin himself was, after all, a JP, the older brother of a barrister, and less likely than most to be ignorant of the law.

He had even been on the bench in animal cruelty cases the previous year, prosecuted by the same local RSPCA Inspector Clarke who had now helped prepare the case against him.

Closed season

Pembrokeshire had only just acquired its own local RSPCA branch, and two of their 22 prosecutions in 1889 had involved the killing of seabirds in the south of the county.

Those cases had not been before Saurin’s own Pembroke bench, but in any case, the existence of a closed season for bird killing was well known and accepted within the shooting community in general by 1890.

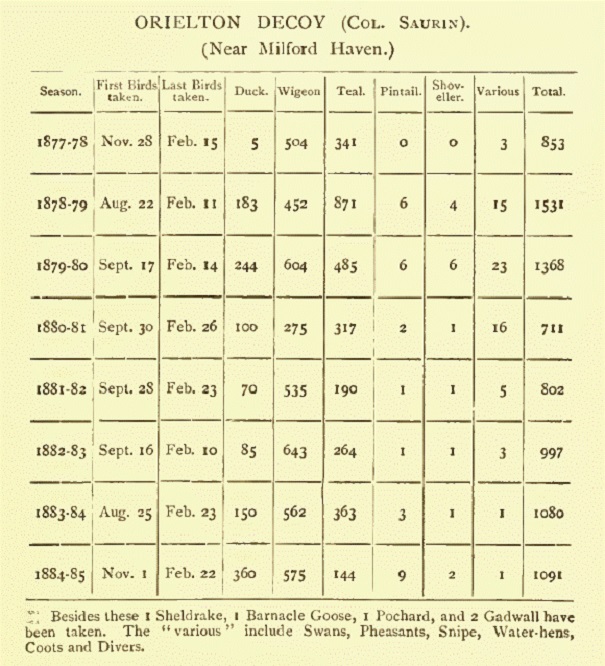

It was certainly respected by Saurin himself. His “Decoy Book,” recording his daily bag of wild duck and other unfortunate birds at Orielton, survives.

It begins in his father’s time, 1877, by which time the original close season on seabirds had already been extended to wildfowl.

The Saurins observed it from the beginning, not starting their trapping and killing before late August, and always ending by the official cut-off date of March 1st.

It’s even possible that the appeal of the trip to Grassholm was precisely that it was an opportunity to have a bit of sport at a time when that was otherwise not allowed, far from land and, the officers thought, the eyes and therefore the reach of the law.

Sentencing decision

The magistrates retired for 10 minutes, which they thought was enough for “very full consideration,” before returning with their sentencing decision.

The case was, their chairman said, “somewhat novel” – “I don’t think we have ever had a case of the same character brought before us” – but “we are bound … to take a certain amount of cognizance of it,” and it “could not be passed over lightly.”

They then proceeded to do just that, with fines of £1/16/0 (£1.80, or £960 in current values) and court costs of almost as much again for all seven defendants – altogether, £22/17/0 (£22.85, or £12,200; about £3/5/0 each), plus their own costs for a barrister and solicitor.

These were not trivial sums, though they were not the maximum available – even first offenders could have been fined £1 per dead bird, of which the Cardiff Naturalists estimated that there were as many as 60 rather than the mere 25 on the charge.

But £22/17/0 was not enough to satisfy all of those who had supported the call for prosecution.

Selborne Society members, for example, “pointed out that if Col. Saurin and his associates were to destroy some rare vase in the British Museum, the penalty would be a flogging and a severe term of imprisonment, while such an offence is, in reality, a much less heinous one than that of destroying some of the rarest of our bird treasures, of far more value than some archaeological curiosities.”

The South Wales Daily News reached a similar conclusion with different reasoning. The Army officers had been “let off” with a “trumpery penalty,” which was “so small that it is probable that not one of the defendants ever think of going outside their doors without a larger sum in their pockets.”

It did not fit their rank and wealth, and it certainly did not fit their crime.

The case was on all fours with one of poaching, but with this difference, that, whereas poachers rarely ply their nefarious calling during the breeding season, these men admitted having destroyed a quantity of birds which the law protects, and humanity, too, during the important period of nesting. Again, a poacher only robs the individual, and not the community. If he eats the game himself he does not consume other food, and if he sells it he does no harm to the public. But the persons who visited the Grassholme (sic) killed the birds simply for the sake of amusement, with no benefit to themselves, but with a distinct injury to the community. Now, many a poacher is fined £2, and to a man who has probably committed the offence through starvation nearly any fine means imprisonment. But what is £1 16s to defendants in the position of those who appeared at the Haverfordwest Court on Saturday?

Cruel and useless destruction

No other press commentary was as well-argued as this, but it was mostly equally uncomplimentary to the defendants and to the Haverfordwest JPs.

Henry Labouchere, the famous Radical MP, for example, took this moral from the case: “The cruel and useless destruction of wild birds should be prevented as much as possible, and offenders should invariably be prosecuted, whatever may be their position.”

He printed the officers’ names in his large-circulation weekly Truth, because “too much publicity cannot be given to such cases.”

“Considering the brutality of the offence … the punishment was grossly inadequate.”

The Field gave a full report of the trial, again with names, as did The Queen, but expressed at least some satisfaction with the outcome: the 1880 Wild Birds’ Protection Act “had been too long a dead letter, and we are glad to learn that at length, through the energy of the Cardiff Naturalists’ Society, an example has been made of the offenders, which it is hoped may have a beneficial effect.”

Critical

Press commentary might have been ever more critical if it had been noted that the magistrates were all Colonel Saurin’s fellow JPs and county councillors and, at the very least, close acquaintances.

One of them, the gentleman farmer and keen huntsman Major Henry Warren Davis of Trewarren, St Ishmaels, was also the commanding officer of the Milford Haven Submarine Mining Militia who had been doing their annual training alongside the regulars at the time of the incident.

Davis was an experienced yachtsman and “splendid sailor,” who claimed twenty years’ familiarity with Grassholm.

He had already written to the local newspaper back in June in an unsuccessful attempt to exonerate his fellow-officers, arguing that the Naturalists had been the trespassers, knew nothing about gannets, and that they, “no doubt from sheer ignorance, did more towards driving the birds away from our coast than anyone who only visits the place for a few hours, perhaps only once in a season.”

Eighth man

He was almost certainly Haig’s unnamed Eighth Man and may even have suggested the outing in the first place.

He was indeed spared to be of use in trying the case, as Haig had explained to the RSPCA’s Inspector Tregaskis when refusing to disclose his name.

Because Grassholm lay within the district of the Roose Petty Sessions, any trial of a crime committed there would come before his bench, not Saurin’s.

But the local newspaper omitted his name from its report of the membership of the trial bench, and those further afield which did include it failed to recognize its significance.

So he got away with his crime, and was then free to subvert his companions’ prosecution.

Read the previous installments of the Gannets of Grassholm here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.