The Gannets of Grassholm, Part 9: Fallout – Thousands More Dead Birds

After the perpetrators of the Grassholm gannet massacre of 1890 were identified as ‘officers and gentlemen’ and tried in a spotlight of media attention, this installment examines how – and if – they were affected by the fallout and what they did next.

Howell Harris

Were there any further penalties for the seven guilty men, apart from the unfavourable publicity? For Colonel Saurin, not obviously.

His regular mentions in the local press continued after the trial much the same as before, chronicling his busy social life and varied interests: the county Chrysanthemum Society, the Yeomanry, the Hunt, horse shows, garrison sports at Pembroke Dock, garden parties at his own and other local grand houses, and public affairs – the Tory Party and the Primrose League, the county council, and, as befitted a good landlord in a time of agricultural depression, the promotion of technical and manual instruction for farmers and their workers.

But he did not turn up back on the Pembroke magistrates’ bench until December. Perhaps he was lying low, in order to avoid further embarrassment? Much of the public anger about the outcome of the case attached to him personally.

The Selborne Society was particularly incensed. He was “the very worst of the whole gang, inclined apparently to glory in his shame, and having no idea of the brutal and unmanly nature of the offence.”

The fact of his being a magistrate made this behaviour even worse, so they wanted “members of both political parties [to] make efforts for his removal from the bench. It would be utterly impossible for any person to have the slightest respect for sentences delivered by one who had himself been convicted of such a disgraceful action.”

Some of this anger may have been because Saurin also had to carry the can for the other magistrate, Major Henry Warren Davis, who had escaped scot free “owing to a conspiracy of silence on the part of his fellow criminals” – a matter that was “irresistible in its sublime impudence”.

This only became known after the trial, when the RSPCA published its Inspectors’ reports on their interviews with the offenders revealing the existence of the Eighth Man and his fellows’ reason for not disclosing his identity. But even then, Davis was not named.

Saurin was not in fact removed from the bench, but as a result of his judicious failure to turn up he had more time on his hands than usual.

The number of ducks and other wildfowl that he bagged on his decoy lake was a reflection of how much he devoted himself to “his own amusement.”

His 1890-91 season began quite early, in mid-September, and was a record: he killed 2,521 birds over the next five months, a quarter to a fifth of all those wintering on his lake, as compared with an average of 1,044 in the five seasons before and 1,165 in the five seasons after.

Consequence

So perhaps Saurin salved his hurt feelings at having been fined for killing gannets (which were, after all, just a sort of seagoing goose) by pitting his wits against his ducks instead, and winning handsomely. The final score: Saurin 2,521; his wildfowl, out for a duck.

Major Edmondes, too, had little to complain about: his promotion to Lieutenant-Colonel came through in September, and he was able to leave Pembroke Dock behind him and start a new challenge in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

For most of the other men, there was no obvious change in their career paths either – they were all still in Pembroke Dock, and still at the same rank except Caulfield, who was promoted to Lieutenant a couple of weeks before his court appearance.

Only Herbert de Haga Haig seems to have had a difficult time as a result of the Grassholm Massacre and subsequent trial.

This was not because of his official reprimand for taking the Sir Richard Fletcher out on a hunting trip that turned into a public-relations disaster. It was a consequence of the local notoriety that had resulted, and his own continuing unfortunate behaviour.

Pennar point

On Tuesday 26th August, a fortnight after the Haverfordwest trial, Haig, another officer, and five “hands” (Engineer soldiers) went out for an afternoon trip in one of the Submarine Miners’ boats from their depot on Pennar Point at the mouth of the Pembroke River.

The people of Pembroke had got used to seeing a pair of swans and their cygnets on the river that summer.

They nested on the mill pond in the middle of town until it was drained, and for the next fortnight they swam up and down on the tide below the mill dam, feeding at low tide on the mud of Pennar Gut in full view of the Miners’ depot.

At least, they did until Haig shot them, killing one adult swan and one of the cygnets immediately. The other swan proved hard to kill, though Haig’s first shot wounded it: the Engineers chased it for three-quarters of an hour, Haig shooting repeatedly until he finally got it.

All of this time they were being watched by Evan Jones the ferryman, rowing his boat to and fro between Bentlass and Pennar two miles below the dam.

They were not in the middle of nowhere, as they had been on Grassholm in May: they were just a hundred yards away from a man who had seen Haig many times before.

Haig was the only person on the boat whom Jones recognized. His honest uncertainty about whether Haig took the shots at the wounded swan too (this happened further from him than the first two kills) did not undermine his evidence.

Haig freely admitted that he had killed both swans, and, with a friend, carried his guns and the carcasses back right through the middle of town later that day, watched by another local man. Henry Williams, a bargeman, also reported that they abandoned the dead cygnet in the bottom of the boat.

Notorious

Reports about this incident to the local RSPCA Inspector, who had only just finished with the Grassholm case, and his report to the London office, set the wheels of justice in motion.

The RSPCA once again decided to haul Captain Haig into court, this time on a charge that he “unlawfully and cruelly did illtreat, abuse, and torture, or caused and procured to be unlawfully, cruelly illtreated, abused and tortured certain animals, to wit swans.”

The unusual thing about this prosecution was that the RSPCA was using a law designed to prevent and punish cruelty towards domesticated animals in order to deal with the shooting of wild birds outside of the close season, though the swans were still accompanied by their cygnets.

Why did it do this, and how could it hope to win?

The why was simple: the Pembroke community was outraged, and Haig was already notorious.

The RSPCA’s local lawyer, Hughes Brown of Pembroke Dock, explained to a magistrates’ court packed with members of the public and presided over by the Mayor himself (but not, and probably not fortuitously, supported by Saurin’s usual presence on the bench) when the case came to trial in October.

“[P]ublic clamour and opinion had … accelerated these proceedings, and public interest in the case had been considerably increased by the fact that the defendant had come under the clutches of the law only a short time ago, upon a charge resembling” this fresh incident.

Outrage

The Pembroke public was outraged mostly by the act itself but also by the fact that it was Haig committing it, and so soon after his previous conviction too. As the South Wales Echo reported (in a quotation omitted by the local press), Brown argued that his acts once again “could not be termed sport in any sense of the word, and nothing would wipe off the stain of killing these innocent animals (applause in court, which was at once suppressed, the bench threatening, if there should be a repetition of it, to clear the court.)”

We can get a sense of the local outrage by reading the letter of a correspondent who called him or herself “Cheerful Horn,” presumably a supporter of decent country sports, to the Canine World magazine before the trial, which was reprinted in full in the local paper.

It started with a somewhat heated recitation of the facts of the recent “great slaughter on Grassholme island,” where Haig and friends “slew the innocents right and left and smashed eggs by the thousand,” firing up the people of Pembrokeshire into a “high state of indignation.”

Their “love of fair play, true sport, and their rare birds, incensed the people greatly,” and the “paltry” fines levied by the Haverfordwest magistrates had not helped calm things down.

And now the town of Pembroke itself was “bristling with bad feeling” towards Haig for his latest offence.

“Not a boy had dared lift a stone at those happy birds” until this “miserable creature” had decided to shoot them, and now the town was “rampant with indignation.”

Haig had left town while awaiting prosecution, but “he will have a lively time of it if he returns.” It would be a standing disgrace to the town authorities if they let this fellow get clear away.

The people of Pembroke have long been famed as sportsmen of the finest class. Let them not lose that name but make an example of the swan slaughterer, if only for the sake of teaching their children that powder and shot were not invented to ruthlessly destroy creatures in no way objectionable to anyone.

There was also a particular reason for Pembroke’s anger about the killing of swans that the shooting of, for example, herons would probably not have elicited.

Anybody who knows the town nowadays will think of swans as very common birds. The millpond is full of them, and stately flotillas have cruised along the shores of the Cleddau and its tributaries, including the Pembroke River, for as long as I can remember (almost 70 years).

Tame

But in 1890 they were extremely rare. There were swanneries on the Stackpole estate 5 miles south of town and at Milton 4 miles east, but David Belt, a 73 year-old Pembroke resident, testified to never having seen or heard of swans nesting on the millpond before.

1890’s pair were thought to have been escapees from Stackpole, i.e. they were clearly domesticated swans, easy to approach, and had arrived the previous year.

They were, Belt said, “far too tame [to be considered as wild], and I should consider myself a brute to fire at them (Applause and laughter).”

People admired and took an interest in them, and could approach within two or three yards; the swans would even take bread from the hand.

Further evidence about how tame they were came from another local who had adopted them, feeding them daily and relocating their nest onto his land because the swans had built it below the spring tide line, and also because he wanted them to breed in his field.

John Owen “had come to look upon them as my property.” He wanted to establish a swannery, but not as a business.

“All that I did I did for the good of the town.”

Heartless

To make their case the RSPCA had to prove that the swans were indeed domesticated, so the evidence about their tameness and Owen’s claim of quasi-ownership were crucial as well as explaining quite why the local public was so angry.

The crowd in court cheered the RSPCA solicitor’s caustic comments on Haig:

[I]f the heartless shooting of a tame swan did not … constitute an act of gross cruelty he was at a loss to know what did. He did not know whether Capt. Haig required the birds for his larder, or for his ancestral hall, but in any case, he ventured to say that not all the skill of the taxidermist would ever wipe out the disgrace that must always attach to the killing of these poor harmless birds. (Slight applause in court.) The defendant was not a common person for whom the plea of ignorance could be raised. He was a man of position, and was clothed with H.M. uniform. He hoped these circumstances would not tend to make the bench take a favourable view of the case.

The point of the last sentence was that this was a case pitting an officer and a gentleman, whose rank had already been enough to get the separate charge against him of carrying an unlicensed gun dismissed, up against the testimony of working-class locals and the sentiment of the town, but before a bench stuffed with the local elite.

In fact the magistrates’ opinion of Haig was almost as critical as the prosecuting solicitor’s and the witnesses’: as the Mayor stated, giving their judgement, “the cygnets were bound to be domesticated animals having been reared in the locality, and … the shooting, or wanton destruction of birds that were perfectly useless to anyone, was … the most unjustifiable circumstance of the whole affair” (or, in the Pembroke Herald’s version, the killing of the cygnet in particular “was a cruel and most unjustifiable act”).

But these warmish words accompanied a dismissal of the case, with no costs awarded to either the prosecution or the defence.

They did not give their grounds for saying that “the charge of cruelty had not been sustained,” but they had evidently concluded that the law could not be stretched to cover the shooting of swans, in however reprehensible a fashion.

Royal birds

The magistrates must have accepted at least some of Haig’s English solicitor’s forceful contentions.

It turned out to be very worthwhile to have hired a man from Dorset to defend him rather than relying on a local man, as he had in the Grassholm case.

Swans were royal birds, and could not be the property of anyone (unless marked, for which there was no evidence).

The cygnets “mixed with other swans, and became to all intents and purposes wild,” though John Owen may have helped rear them, and they might have settled on his land.

In any case “It was preposterous to suppose that if a person went out shooting, and killed a swan, he was to be proceeded against for cruelty.” There had been no cruelty, even in the long pursuit of the wounded swan. “The bird was shot and then followed immediately, and killed.”

Haig had behaved in a perfectly “sportsmanlike” way throughout. He “was an officer and a gentleman against whom nothing of the kind [cruelty to animals] had ever before been preferred,” conveniently overlooking the recent Grassholm Massacre because it had depended on the simple fact of killing during the close season, raising no issue of cruelty.

The case was “only the out-come of private spite entertained by some individuals against his client,” and “an intolerable persecution.” It had been made “as bad as possible against Captain Haig, because of some unaccountable feeling of antipathy against him in the town.”

Despite its outcome, the case was evidently very newsworthy, with long reports not just in the local press but in the Cardiff Times, South Wales Echo and Daily News, Western Mail, and Weekly Mail. Haig was once again somewhat famous, but for the wrong reason.

Not that this necessarily meant that he experienced ostracism from the social circles he moved amongst: a week after the trial he was back judging the art competition at the Chrysanthemum Society’s annual show. But his everyday life in Pennar, Pembroke, and the Dock must have been at least a little bit awkward for a while.

Still, the Royal Engineers did not hurry to move him on: he remained in post until May 1892, when he became Adjutant to the Newcastle-upon-Tyne Volunteer Engineers, i.e. the same job that he had held in 1887-1889, only in a different port.

Career

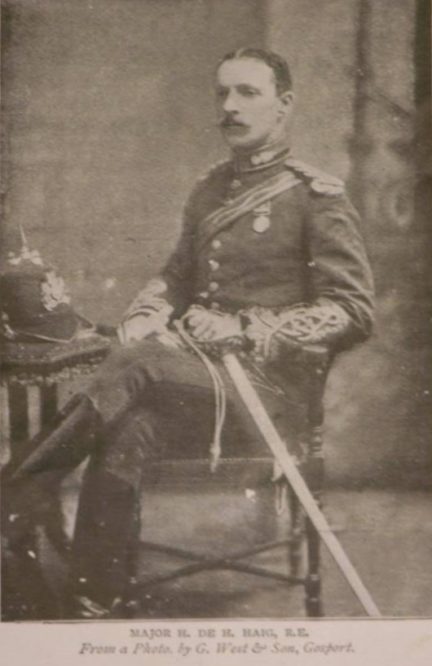

His career may not have been very exciting, but his progression through the ranks had not been harmed, because advancement was strictly by length of service. When he was promoted to Major in July 1893, it had taken him exactly the same time as the average for all of the thirteen fellow-Captains upgraded alongside him, 19.8 years (range 19.6 to 20 years) since his first commission. The fact that, uniquely among them, he had passed the Army Staff College no more counted in his favour than summer 1890’s embarrassments weighed against him.

By the end of 1894 he was considering leaving the Army before he turned 40, a subject he raised in a letter to his old friend Teddy Roosevelt, but for some reason decided not to – perhaps the arrival of his children in 1891 and 1894 helped explain this. He soldiered on in Newcastle for five years, then moved to India where he revived but also ended his full-time career, escaping the Submarine Mining Service at last.

He commanded one Engineers base after another (Allahabad, Poona, Calcutta, Madras) before returning to be Commanding Royal Engineer at Chatham in 1904, receiving his final promotion to Colonel, and retiring on half-pay shortly before he turned 50.

He lived on for another forty blameless years, only appearing before the Cheltenham magistrates for his erratic driving in his 80s, and dying there just before the start of 1945. He was remembered as a keen amateur gardener, an expert in fruit tree pruning, a painter in watercolours, and a skillful wood carver. Of his youthful exploits as a sportsman, not a word.

Author’s Note: anybody who wants to see a home movie about the Orielton Duck Decoy after its revival in the 1930s to catch birds for ringing, recording, and release rather than killing and eating can watch one free on the BFI site.

Read the previous installments of the Gannets of Grassholm here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.