The Gannets of of Grassholm, Part 6: Loving and Killing – Victorians and Bird Protection

Howell Harris

This week’s episode is different in character from all of those that have preceded it, and all that will follow. It expands on the question with which I began Part 5 – why did the acts of a few men one Whit Monday afternoon on Grassholm turn into a country-wide scandal? – to put its answer into a national context.

Britain’s first and, in the 1880s, still strongest animal protection society, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, was founded in 1824 and received its royal charter in 1840.

By the 1860s it was beginning to move beyond its original mission – reducing cruelty towards domesticated animals through education, publicity, legislation, and prosecution – to include the protection of wild birds, their nests, and their eggs.

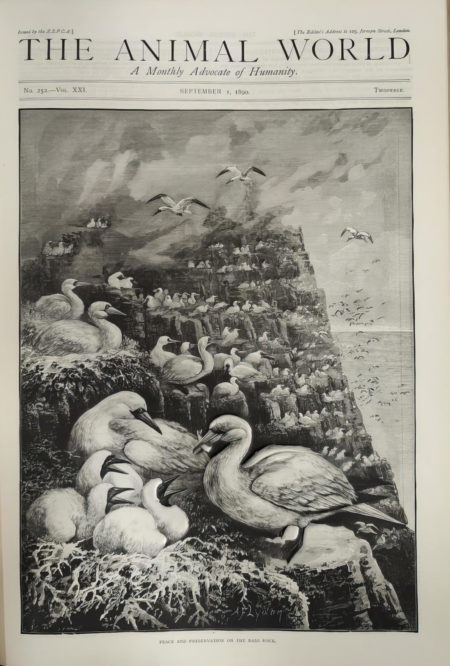

The RSPCA played a key role, together with the British Ornithological Union and the British Association for the Advancement of Science (the umbrella body for local naturalists’ societies like Cardiff’s), in stimulating the formation in 1868 of the East Riding Association for the Protection of Sea Birds.

Lobbying

This was a response to a problem that was particularly acute around Flamborough Head: the organised shooting by day-trippers of huge numbers of seabirds, as well as the large-scale slaughter of many more to satisfy the new fashion for elaborate feathery hats.

The Manchester Guardian reported that 107,250 had been shot in four months, 8,000 of them in one week by just 11 people.

The campaign was quickly successful and Britain’s first wild bird protection law, the Sea Birds Preservation Act, passed Parliament with bipartisan support in 1869.

Its key provision was a ban on killing or injuring 33 different sea-bird species, including gannets, during their breeding season, defined as 1 April – 1 August, with fines of up to £1 a bird for offenders.

Through the 1870s similar protection was extended, first to wildfowl, and then to a long list of other common birds of no particular economic value.

The RSPCA and the British Association continued to collaborate in successful lobbying on their behalf.

Finally, in 1880, previous piecemeal laws were repealed and replaced by a comprehensive Wild Birds Preservation Act, protecting birds from being killed, trapped, taken, or sold within the breeding season, which was extended to 1 March-1 August, and again prescribing penalties of up to £1 per bird.

Its principal advocate – one of three Liberal sponsors – was the prominent Radical Lewis Llewelyn Dilwyn, MP for Swansea Town, a leading local industrialist and also an enthusiastic ornithologist.

Weakened

The Act was full of exceptions and omissions, was unintentionally weakened by supposedly clarificatory amendments in 1881, and it is hard to know how effectively it was enforced. It was not the RSPCA’s top priority, but it was not a dead letter either.

In September 1887, for example, the Society’s barrister Robert Colam prosecuted about twenty men from Sunderland and South Shields who had taken a day trip to the Farne Islands by boat on August Bank Holiday in order to blast away drunkenly for hours with their breech-loading double-barrelled shotguns and a thousand cartridges.

They shot at anything that flew, into flocks of kittiwakes and puffins and at their nests, as well as at the Ecclesiastical Commissioners’ local watchman who attempted to get them to stop.

Their reasons were that it was “fun” and “practice.”

They claimed to believe that it was open season, but in fact the closed season on the Farnes had been extended by a fortnight precisely because of previous raids, to give young birds time to quit the nest, and the RSPCA had posted notices along the north-east coast to advertise the fact.

Activism

And in June 1888 the Society’s long-serving and energetic Secretary, John Colam (Robert’s father), boasted of its activism and success in using the Act against offenders.

It had secured more than 30 convictions in the previous month for “taking or having in possession unscheduled birds,” i.e. those enjoying even less protection than gannets enjoyed.

So there were certainly some high-profile and successful prosecutions. But in general the RSPCA’s attention remained focused on domesticated animals.

In 1889, for example, the monthly return for the height of the breeding season showed only eight convictions under the 1880 Act out of 552 successful prosecutions altogether, or 1.4 percent; and the overall 1889-1890 tally was just 60 out of 5,886 convictions secured, i.e. about 1 percent.

In March 1892, the start of the close season, the same number of people (two) were convicted of offences against wild birds as for “inserting mustard in the private parts of goats.”

Opposition

Notwithstanding the Act’s weaknesses and any laxity in enforcement, public opinion opposed to animal cruelty in general, and killing birds in particular, was clearly growing and becoming more organised and vocal in the 1880s.

The East Riding Association had only been local and temporary, disbanding almost as soon as it achieved legislative success. Its successor, the Association for the Protection of British Birds, was equally short-lived.

But in 1885 England acquired its first lasting, general-purpose conservation group, the Selborne League, which in 1886 joined forces with the Plumage League, a women-only organisation, united by their opposition to the trade in exotic plumage for costume decoration, to form the Selborne Society for the Protection of Birds, Plants and Pleasant Places.

It had a broad scope – “the preservation of birds, wildflowers and ‘forests and places of popular resort by means of publishing any threatened destruction of them’” – and it elaborated on these aims as it grew into a network of local societies, chiefly in the South of England.

The fact that it was not single-mindedly focused on the “feather fight” left space for the separate organisation of those who were, particularly the Society for the Protection of Birds in 1889, the nucleus of the RSPB.

Public opinion

So by 1890 there was already an organised public interested in the evils to which the laws of 1869-1880 offered a response, however inadequate, and ready to react to egregious violations of them.

This was the public to which Thomas Thomas directed his campaign and, as we have seen, it responded as he hoped. An interesting feature of this public opinion was, as we saw in Part 5, how broadly based it was, and how far it reached.

The RSPCA enjoyed elite sponsorship and strong upper- and middle-class backing. In some ways these made it cautious and limited. In particular, it was reluctant to make an issue of the country sports so many of its supporters engaged in, and all of which involved the slaughter of wild or reared animals and birds.

But this also presented it with an opportunity. Even within the sporting community there was support for the prohibition or regulation of killing that was deemed “unsporting” – not involving pursuit, some skill, an element of uncertainty, and, at least in theory, a chance of escape and survival for the prey. And there was a complementary willingness to clamp down on the activities of people who were not respectable sportsmen.

Controversial

So the mass slaughter of sea birds around Flamborough Head at the time of their greatest vulnerability, by groups of urban and bourgeois or lower-class day trippers, simply for the hell of it and with no conceivable justification (such as game animals’ and birds’ place in the human diet), was the ideal target for setting the precedent of legal protection.

Wild bird protection enjoyed bipartisan and community-wide support from the first. After the 1869 Act, gradual extension of the laws’ scope, justified on other grounds – the usefulness of some of the species to be protected, their beauty and charm, or their increasing rarity – continued to meet the same broadly positive reception.

There was a further reason why some members of the country sporting community embraced the piecemeal, limited extension of the laws. Hunting and shooting were also becoming controversial activities in late Victorian Britain themselves.

They were emblems of the privileged lives of the aristocracy and gentry and the gross inequalities in access to the countryside that resulted from the great estates, their armies of gamekeepers, and the Game Laws that protected them.

Bird killers

Wild bird protection laws offered spokesmen for country pursuits a way of, in Brian Bonhomme’s words, “clean[ing] up the image of sport hunting by isolating and excluding what many among the elite felt to be its most unlovely – and visible – practitioners.”

Supporting these laws also offered shooting estates a new way of justifying themselves and the Game Laws they depended on: they, too, were practising wildlife conservation, in their own special way, the same argument still deployed by the British Association for Shooting and Conservation today.

Thus the South Shields and Sunderland August Bank Holiday bird killers were perfect examples of the sort of activity, and the kind of people, that almost everybody agreed deserved to be prosecuted.

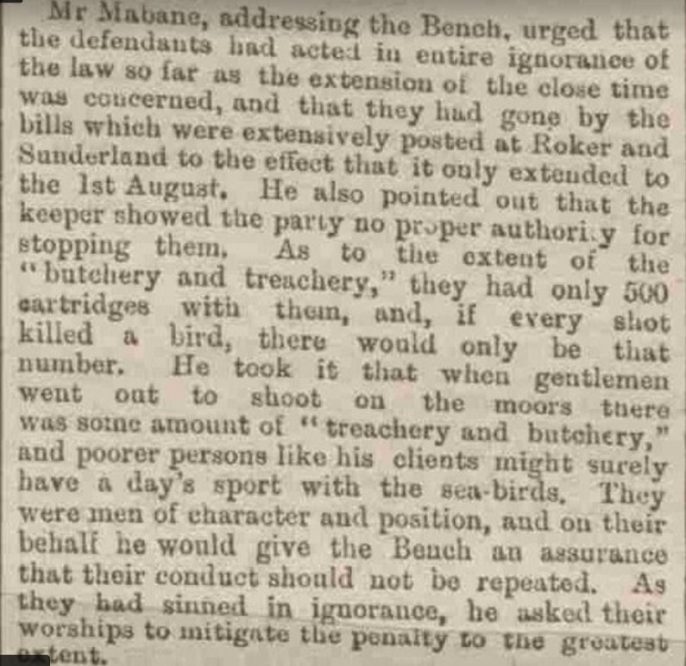

Their lawyer’s protest that “when gentlemen went out to shoot on the moors there was some amount of ‘treachery and butchery,’ and poorer persons like his clients might surely have a day’s sport with the sea birds” did not move the magistrates of Belford to temper justice with mercy in their case.

The killers were a mixed bunch. A “gentleman,” a grocer and Councillor, a barman, a tobacconist, and a tug-owner were convicted of shooting and fined, with another gentleman, a pilot, another barman and tobacconist, an innkeeper, two engineers, and a foreman smith also in the party but let off with a costs order against them.

These were not members of the lower orders – most of them were skilled workers or small businessmen – but they had behaved like brutes and were treated accordingly. A precedent for how to respond to the Grassholm Gannet Massacre had been set.

‘Sportsmen’

One result of this evolution of thought and rhetoric was that arguments in favour of respecting the close season for almost all birds (except “vermin” species) came to be accepted and advanced by “sportsmen” themselves, or at least by those who wrote, and claimed to speak, for them.

In February 1891, for example, the Sporting Gazette drew its readers’ attention to the coming end of the shooting season:

Nesting time is fast approaching, and the sound of the breech loader should no longer be heard in the covers, or on the moors, or by the sea. From to-day even the wild duck and the woodcock, the snipe and the seamew, are safe from the wiles of the persevering gunner, under the protecting shelter of 43 and 44 Victoria, cap. 35.

This was a cause for celebration and even self-congratulation, not regret: “now the sportsman realises in truth that there is an end for the time even to bird shooting of all kinds, for pairing seems to be in the air…. Verily the Wild Birds Protection Act is one of the most appreciated legislative enactments during the reign of Her Gracious Majesty,” and the only thing wrong with it was that it did not go far enough.

These developments in public opinion and public policy over the previous generation explain why news of the Grassholm Gannet Massacre was met with such widespread anger.

It was, the RSPCA thought, “the most wanton violation of the law for the protection of birds” that had occurred since the passage of the law in 1880. They and others were determined to see it enforced in this most important case.

Author’s Note: I should like to thank three scholars whose arguments, advice, practical assistance, and encouragement were invaluable to me in writing this article: Prof. Brian Bonhomme, Youngstown State University; Prof. Sir Brian Harrison, Oxford University, the premier historian of the RSPCA as well as of much else; and Dr André Keil, Liverpool John Moores University.

Read the previous installments of the Gannets of Grassholm here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.