The Last Invasion

Hywel M. Davies

On the 22nd of February it will be 228 years since the French landed on the Pencaer peninsula.

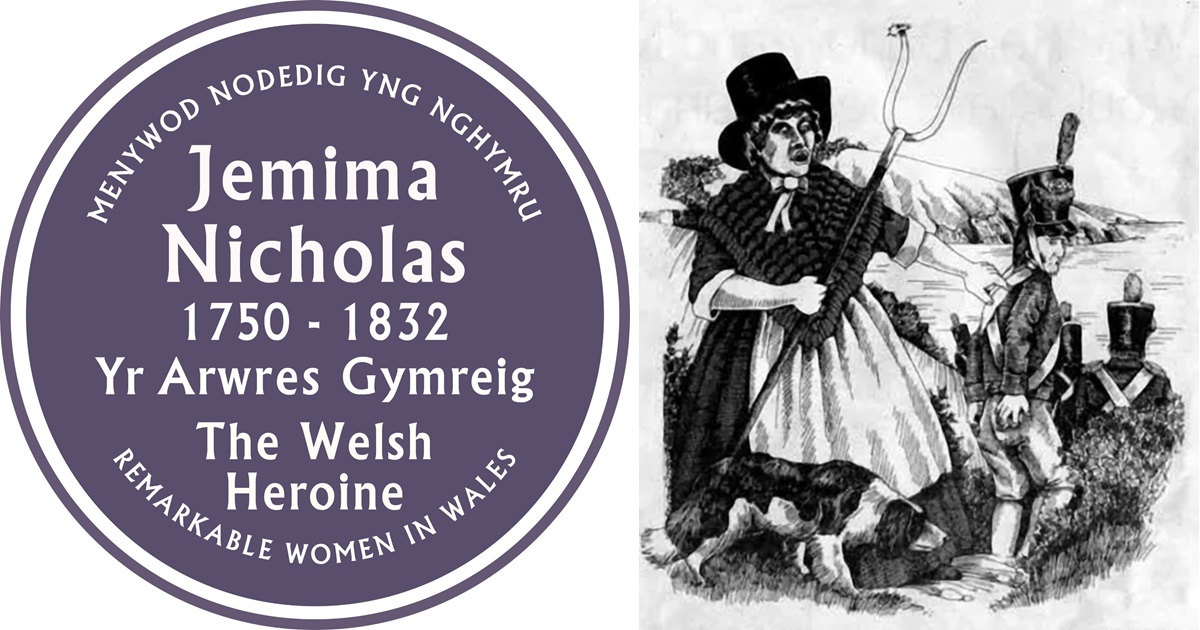

What predominates in the popular mind is women in their red petticoats and the heroine Jemima with her pitchfork. Jemima Nicholas is one of the most memorable and well-known figures in Welsh history, but her name was not recorded in print until 1842, a generation after the Invasion.

Often dismissed as a semi comic incident, a mixture of French farce and Welsh flannel, the French Invasion was a serious, deadly affair – men were killed, and women were raped.

The history of the Invasion has been a partial history dominated by certain traditions. Narrators and historians of all types shaped the narrative by selecting sources they judged “authentic” and neglecting others.

The established account of the French Invasion is largely a story of Pembrokeshire men of high social and political status.

Lord Milford and Baron Cawdor headed the list of the great landlords of the county and were responsible for its defence. In military history tradition the French invasion is their story.

Oral tradition

It is in oral tradition and in social memory that the women were remembered or misremembered.

There are several types of women in the Invasion history.

Women have often been marginalized and forgotten as victims but also celebrated as heroines.

The expedition led by William Tate, an elderly American of Irish origin, was played down by the British Government very soon after the event, as a French attempt to rid itself of unwanted criminals.

As well as criminals, many of them political prisoners, there were crack grenadiers in the French force, La Légion Noire, which also had Irish officers and American soldiers in their midst.

Their purpose was to terrorise, and in this they succeeded. After initial despair, the local people fought back with vengeance against the hated enemy who were pillaging their property, eating their livestock and threatening their lives.

Bloodlust

It was their behaviour, not their ideology nor their religion, that concerned them. Stories that circulated both at the time and later stressed the bravery and bloodlust of the Welsh peasants – French bodies were pierced and skulls bludgeoned.

Eyewitness accounts reported on the widespread reaction, the popular fury, against the French before the militias arrived, irrespective of age or gender. The Welsh, it was said, fought as Ancient Britons, who had never been defeated by invaders.

Tate acted alone but, under pressure from his officers, surrendered without many of his soldiers, who were dispersed, drunk and demoralised knowing.

Later in the twentieth century, it was called the “Battle of Fishguard”, but nothing could be more wrong. Tate deliberately avoided military confrontation to avoid unnecessary bloodshed, it was a “Surrender”, not a “Battle”. Tate never stepped foot in Fishguard.

The account of the “Surrender” was presented officially by Cawdor to the Home Secretary. The security of the Empire was at stake, as an orderly, well-managed process from negotiation to the universal laying down of arms. This put the “Surrender” in the best light for the authorities in London.

The French surrendered piecemeal and often reluctantly.

The position on the 24th, only two days after the landing, when most of the French capitulated, was confused, the outcome uncertain and as much in the hands of the peasantry as the military .

The development of the story was connected inextricably to the place where it was most popularly associated: Fishguard. Fishguard prospered by the new sea route to Rosslare, opened fully in 1906, and a later Atlantic crossing.

Tourism asset

The French Invasion heritage became a tourism asset, cleverly publicised by the Great Western Railway. On occasions of civic pride, such as the Mauretania coming to Fishguard in August 1909, girls dressed up in the clothes they associated with the Invasion and their own families’ past.

A trip to Fishguard was to tread on significant historical ground, ground which had witnessed the Last Foreign Invasion of Britain as it was called by the locals at the Centenary in 1897.

When the Last Invasion imagery was at its height just after the Second World War, and the fear of invasion a recent memory, Tate was at last given his dues.

A complete nonentity stood on British soil in command of invading troops, which was more than Napoleon or Hitler ever did.

The storytelling peaked at times of war and invasion fear. It continues to be told and is still relevant today.

Hywel M. Davies’s The Last Invasion: War, Women and Memory 1797–1997 newly published by the University of Wales Press, highlights the social and cultural imprint of the French invasion and tells how the Invasion inspired literary figures as different as Wilkie Collins, Ceiriog and Harri Webb, whilst academic discourse and scholarly texts conflicted with popular and local memory.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

I’m amazed this story hasn’t been Hollywooded.