The road to Niseko

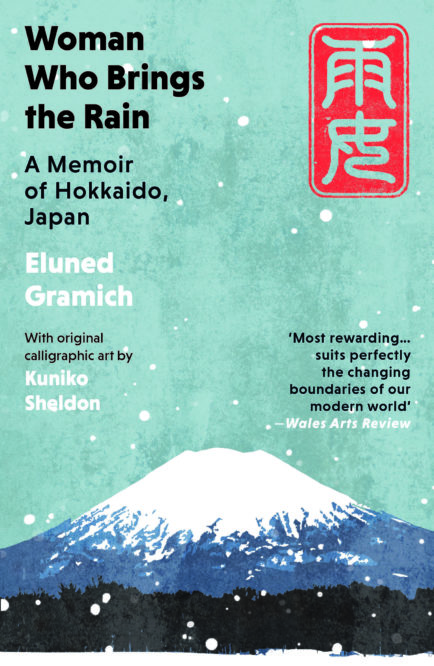

Eluned Gramich reflects on her award-winning memoir Woman Who Brings the Rain as it is published in a new edition

It has been ten years since I last set foot in Japan; ten years since I finished writing Woman Who Brings the Rain in the teenage bedroom of my parents’ house.

I was another person then: in my mid-twenties, with that see-sawing combination of confidence and insecurity which, I think, is characteristic of that decade.

I wrote Woman Who Brings the Rain because I wanted to remember what I’d experienced in Hokkaido some months earlier. I thought that I was somehow qualified to write about Japan, having lived there for almost two years and having made efforts to learn Japanese – passing the Japanese Language Proficiency Test N2 exam after only a year of study.

Years afterwards, I admit I felt some embarrassment that I was so quick to put pen to paper; to believe that my comments on a culture I was only briefly acquainted with might be meaningful.

Yet now, on coming back to the text, I see that my tentativeness is everywhere, and I’m glad of it.

In the first chapter, I describe the strange experience of listening to Japanese – the muffled world of half-understanding that a learner reaches at the murky ‘intermediate’ stage of language-learning – and this image is, for me, at the heart of the book as much as the mountain, Yōtei-San.

I was a foreigner, trying to reach another culture, another language, from a place of imperfect understanding. But this is part of the book: admitting the impossibility of truly capturing another culture when you haven’t grown up in it.

A culture can’t be ‘captured’, in any case. As a writer, as a foreigner, you can only be an observer and eavesdropper. By its nature, observation is limited to one viewpoint, one eye-line; eavesdropping offers snatches of a longer, more complex conversation. I hope that these muffled conversations still speak ten years later.

Mountain

The way of the valley is an immense tongue; the form of the mountain is a body most pure. Master Rujing

The road to Niseko runs through forest, and farmland, and forest again. The car winds around the hills, moving from dark to bright patches, and dips down into the valley.

The sun, filtering through the broad, green maple leaves, plays like an old film reel across the windscreen. I catch sight of thin-limbed deer, trotting along the roadside, before slipping in between the tree trunks. Their tan-brown bodies dapple with the woods.

A line from an Ainu fairytale comes back to me: The roots, they wrote, of certain trees are known to turn into bears. Perhaps certain trees also turn into deer.

My host family, the Tatenos, are sitting in the front seats. They don’t seem interested in the animals, which they see every day, or the different trees, or the camellias blooming furiously in the undergrowth. Instead, when we drive into open terrain, they talk to me about the population size, building works, crops.

The vast fields remind me of eastern England, where I once studied, but the vegetables here are different. Potatoes and cabbages, of course, but also edamame beans, sweet Hokkaido pumpkins, daikon, nagaimo, wasabi root. The giant greenhouses send shocks of light onto the surface of the road.

For miles and miles there is not a single house. Then they appear – one, two, three. And then nothing again. The houses themselves are otherworldly. There is no uniformity to their architecture, no sense of style. Here is a ski chalet; there a bungalow; a villa, a shack with a roof of corrugated zinc.

Tateno-San explains to me that rich Tokyoites buy up land and build their own dream homes. If he’s lucky, they’ll buy the land from him. His mobile rings. Tateno-San, one hand on the wheel, takes the call.

‘Dōmo,’ he says as a greeting, elongating the ‘o’. This is manly speech: casual, confident and managerial. No one I know from my Japanese school would start a conversation this way. ‘Dōmo,’ he says again at the end.

The welcome card the Tatenos sent me is still in my coat pocket. The card contains a basic list of information: their names (Takashi and Kuniko Tateno) and the name of their dog (Hana), their ages (64 and 62) and hobbies (golf and saké for him; books for her).

The only personal touch was a line at the bottom of the page, scribbled in kanji, which I spent a long time mistranslating: ‘We are so looking forward to meeting you, we could cut our throats.’ They’d also enclosed a photograph of the two of them, and their dog Hana, sitting in their living room.

The image showed them distracted, unsmiling, perhaps worried about the timer on the camera, or about Hana keeping still. Now they sit in front of me, their faces partially obscured, their quick speech – like all Japanese – flowing in and out of my comprehension, as if I were eavesdropping on a conversation going on in another room.

Without a word, Kuniko opens a bottle of water and brings it to her husband’s lips.

‘This is Niseko-chō,’ he continues, after having a sip. ‘Chō is what we call an area. The town itself is further down the road.’

We turn off down a one lane road. The beginning of it is decorated with little piles of pumpkins: the lurid orange kind I’d seen in the supermarkets in Tokyo.

‘They’re too big to sell so we put them by the road. They’re all over town,’ explains Kuniko. We pass two small farmhouses. A dog – a Hokkaidan hound – barks wildly after us. We dip into another pocket of woodland and suddenly the world is muffled by the pines, maples and conifers.

When we come out the other side, I see, suddenly, a baffling, extraordinary form erupting from the farmland in front of us. A shape so startling that I’m at a loss as to what to say. The timid repetition of the word kirei or ‘beautiful’ won’t suffice. A mountain floating in the air, its outline hazy in the pale sky. Although the summit is hidden by mist, I can make out the slopes’ mossy green, rolling down from the cloud for miles and miles on either side. Its triangular shape reminds me of the muscled neck of a sumo wrestler.

‘What is that?’ I ask.

‘Yōtei-San,’ Kuniko replies. ‘Hokkaido’s Mount Fuji.’

The colours grow clearer as we approach, like the brushstrokes of a painting. Yet the scale of the mountain seems only to increase, becoming ever more distant, impossibly high, unattainable.

‘Yōtei-San,’ I repeat, testing the new word.

Kuniko nods before popping a boiled sweet in her husband’s mouth.

Woman Who Brings the Rain by Eluned Gramich is published by Parthian.

Her most recent novel is Windstill published by Honno

An exhibiton of the kanji prints of Kuniko Sheldon which accompany the new edition of the book is being held throughout October at the Y Cartws/The Coach House, Shingrig, St Dogmaels, Pembrokeshire SA43 3DX

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.