The widow, the dogs, the ghosts, and the smoker: Daniel Owen’s shorter fiction

Adam Pearce Llyfrau Melin Bapur

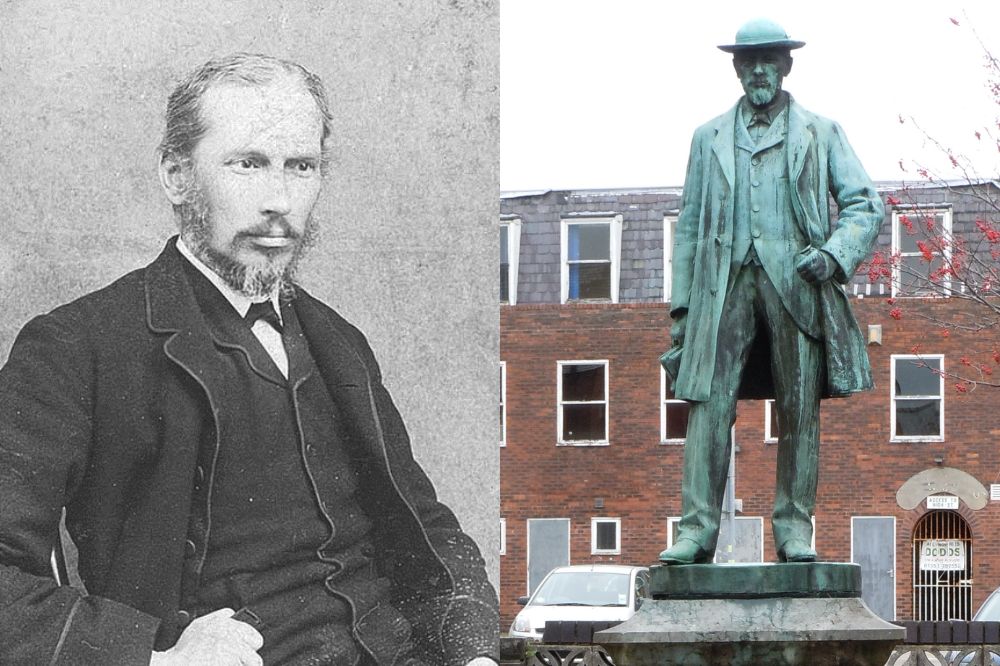

If you are familiar with any literary figure in Welsh from the nineteenth century then you are probably familiar with Daniel Owen, the novelist from Mold in north-east Wales who has been variously described as the most important Welsh-language writer of his age, the first great Welsh novelist, and sometimes even (less accurately) as the first novelist in Welsh.

He is less renowned as a poet and short story writer, but in fact wrote in both genres alongside his career as a novelist, and whilst his work in them doesn’t demand a great revaluation of where his talents lie it offers a fascinating insight on the man himself, as well as (in the case of the stories) having a small but important role in Welsh literary history.

Most of Owen’s short stories date to 1894-5, in his final years and after the publication of his last novel, Gwen Tomos.

A number of them appeared in Cymru’r Plant, O. M. Edwards’ magazine for younger readers, and were then collected in a volume, Straeon y Pentan (Fireside Tales), which was his final published work.

Growing popularity

Short stories in Welsh had started appearing in the Welsh press in the eighteenth century and were extremely popular by Owen’s time, with maybe a half dozen appearing each week in a number of different publications throughout the 1880s and 90s.

Nevertheless Owen’s volume has an important place in the history of the genre in Wales as it was actually the first ever collection of Welsh short stories to be published as a self-contained book, and under its author’s name.

In a time when so much prose was published anonymously this was an important step forward for the genre in Wales.

It was also noteworthy that the book was not particularly marketed at children even though most of the stories had originally appeared in a children’s magazine, further emphasizing the validity of this kind of fiction as a serious enterprise.

The collection itself, however, is a bit of a hodge-podge.

Although the material can all be dated to more or less the same period (some was written specifically for the book’s publication in 1895; alongside this and the Cymru’r Plant stories there are a few pieces which had originally appeared in Owen’s newspaper column in 1892) it varies greatly in tone, subject matter and quality.

The simplest pieces like Enoc Evans y Bala and Thomas Owen Tŷ’r Capel are not really stories at all but rather character portraits or amusing anecdotes, some of which barely take up more than three or four pages.

Some stories such as Y Ddau Deulu are marred by rather heavy moralization. It is perhaps significant that Owen’s health (never strong) was in decline at this point.

These are exceptions however and the majority of the stories in the volume work perfectly well as the sort of folksy tall-tales one might hear in a pub (where, it seems, Owen may have harvested them); and the best are very clever showpieces of the author’s witty style which offer (like the author’s longer fiction) a fascinating insight into working-class society in 19th-century Flintshire.

There are comic stories about pranks and misfortunes, two ghost stories, several stories about remarkable dogs, a romantic tragedy and some cautionary tales. Their short, straightforward nature makes them great for Welsh learners (and indeed children) as well.

Rising

The stories in Straeon y Pentan may be his better known short works, but Owen had in fact experimented with shorter fiction much earlier in his career.

Published in 1886 to cash in on his popularity after the success of his novel Rhys Lewis, Y Siswrn is a miscellany of various works that had appeared over the preceding decade, including Cymeriadau Methodistaidd, his first piece of prose fiction.

It also contains the short story Yr Ysmygwr, probably the best of his shorter fiction. It describes an interaction that takes place on a train between various unnamed characters: a priest, a widow, a rather eccentric gentleman (the titular Smoker) and a boorish, self-satisfied narrator.

Whilst it sounds like the setup to a joke it is in fact an interesting exploration of propriety, charity and hypocrisy in Victorian Wales, with the smoker’s obvious “eccentricity” being (as often in Owen’s fiction) a smokescreen to allow him to speak as others cannot.

The hypocritical priest, who refuses to give for the poor widow, becomes the victim of this remarkable tirade:

“Pa fath bobol, syr, ydach chi yn ein galw ni y Cymry? Slaves dienaid a di-ynni yr ydw i yn ’u galw nhw, yn diodde y pla yma ers oesoedd. Mi fyddaf yn synnu na fasen ni ers talwm wedi codi fel un gŵr i ymlid y lot ddiog hyn oddi ar ein porfeydd! Maent yn casáu ein hiaith, ac wedi gneud eu gorau i’n cael dan draed y Saeson, ac ar yr un pryd y maent yn bwyta braster ein gwlad a chynnyrch ein tiroedd—a ninnau a’n llaw wrth ein het iddynt am neud hynny!”

“What kind of people, sir, do you call us Welsh? Slaves without souls or energy I call them, suffering this plague for ages. I’m surprised that we haven’t long ago risen up as one to drive this lazy bunch from our pastures! They hate our language and have done the best to put us under the boots of the English, and at the same time they eat the fat of our country and the produce of our farms—and us with cap in hand to them for doing so!”

Joy in life

Whilst Owen’s poetry is more workmanlike than inspired, it is largely free from the bombast which is such a plague on much Welsh poetry from the period.

Some of the poems which have survived include examples written as a young man some twenty years before his first published prose works, and see him tackling material that few would associate with Owen, as in Y Troseddwr, a poem about a man facing execution.

His finest poem perhaps is his last, Ymson Bore Nadolig 1894, which describes the poet in a deep depression who is then inspired by hearing birds singing on Christmas morning to try and find joy in life.

The aforementioned story gives its title to our new volume of Owen’s shorter fiction and poetry Yr Ysmygwr, which includes the entirety of the miscellany Y Siswrn alongside a number of new poems, prose pieces and stories which have never been previously published outside periodicals; as the volume of this new material runs to 58 pages we decided to use a different title to differentiate this new book from previous publications of Owen’s work.

Alongside Straeon y Pentan, this volume contains almost all Owen’s shorter fiction and poetry and we were pleased to launch both volumes at this year’s Daniel Owen Festival in Mold.

Straeon y Pentan and Yr Ysmygwr (which contains Owen’s Y Siswrn) are available from www.melinbapur.cymru for £7.99 and £8.99 respectively, as well as from a range of Welsh bookshops.

The present author’s English Translation of Straeon y Pentan, Fireside Tales, was published by Brown Cow in 2011 and should still be available.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.