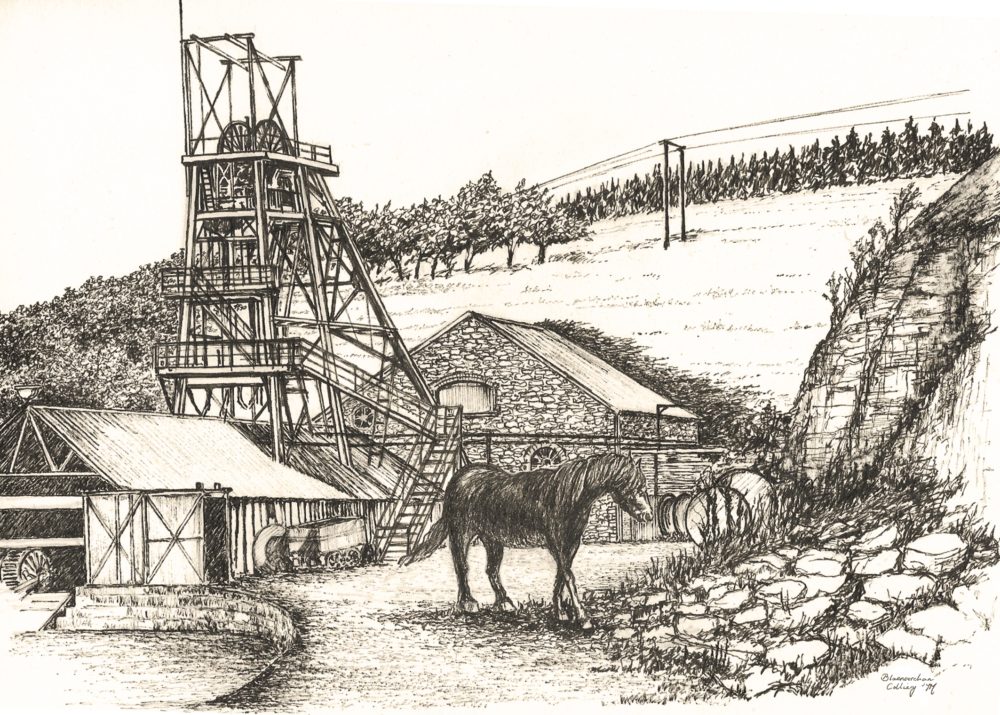

Y filltir sgwâr/The square mile: Blaenserchan colliery revisited

In a year long series Tom Maloney, from Abersychan, shows how you can love a place so well it becomes a part of you.

I remember reading Richard Llewellyn’s ‘How Green Was My Valley’ and Alexander Cordell’s ‘Rape of the Fair Country’ in my teenage years. They are such iconic stories of their time that have the power to stir your soul.

Looking back I know I found these stories inspiring and they certainly helped to frame my thoughts about industrial history.

One thing in my mind has changed. I had thought that the heavy industrial impact on the landscape would never allow it to recover and that the valleys would be inevitably scarred for all time.

But … in many places the valleys have blossomed and transformed beyond recognition and beyond belief really into green spaces once again, where it is difficult to comprehend that coal and iron were once king and master.

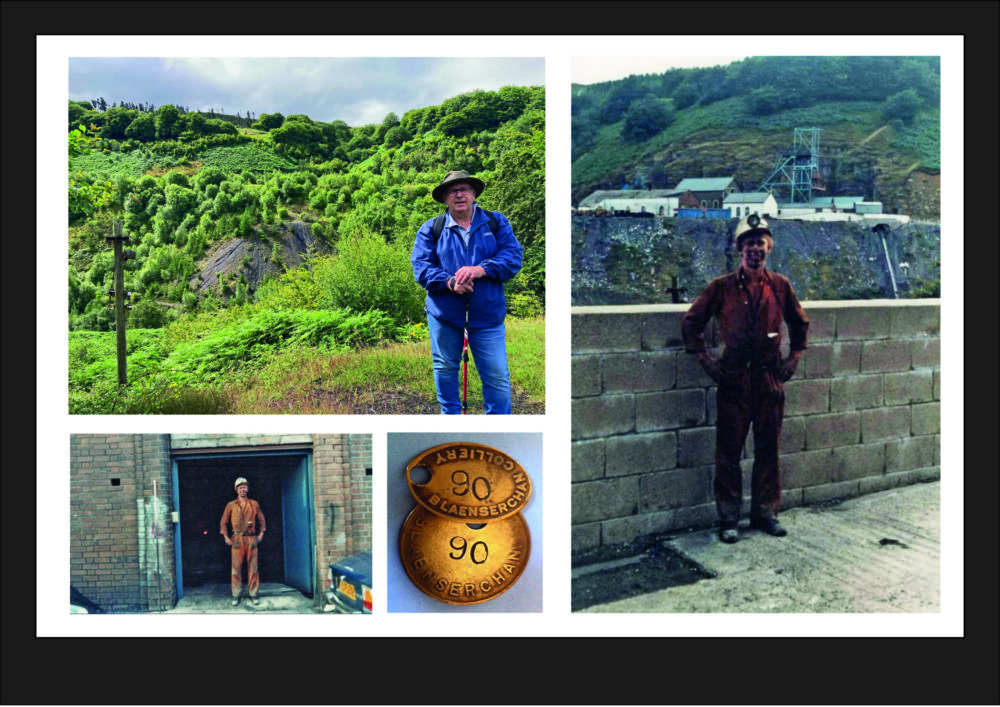

I count myself very lucky this week to have been be joined on a walk to the site of Blaenserchan Colliery, just over the hill from The British, by Phil Watkins who worked at the pit for eleven years until it closed in 1985.

I had taken some photos and done a little sketching onsite in the 1980s, but in recent years I have walked the old pit road many times, often wondering why I did not take more photos then and try to record some of the life of the colliery as well.

The old pit road is a green road now and its history is wrapped in spreading ferns, wild flowers and butterflies.

It was fascinating to talk to Phil, who has so many good memories of his time at Blaenserchan. We could not have picked a better day to meet up and our walk began with an amazing chance encounter.

Face from the past

As we were just starting to chat out of the corner of his eye Phil recognized Alan Boucher, a face from the past. Even after thirty years it was clear that the bonds formed through their work underground together were still as strong as ever, there was immediate banter between them, they were comrades.

Alan worked underground for eighteen years, with ten years at Blaenserchan.

“I was top notch! (Lots of laughter between Alan and Phil) I worked underground in repair and development. After you worked the coalface so long you exhaust the face. So you have to get another face ready for when the one shuts the other is open. If they had a fall somewhere, or if they had ‘a bit of weight coming on’ and the rings were buckling I would have to take the old rings out, repair the ground and put in new. That was my job.”

You can hear part of the conversation here.

I felt a sense of privilege to have been able to listen to them chat and there was fondness in their farewells to each other.

As we continued our walk our conversation turned to starting work at the colliery as an apprentice electrician in 1976 and what it was like to work there.

Incidentally, this was no small achievement. I remember that apprenticeships with the National Coal Board were much sought after at the time.

Phil who grew up in Garndiffaith, followed in his Grandfather’s footsteps, also from the ‘Garn’, in working at Blaenserchan.

“The mine had stopped winding coal and was only used for winding materials and men. The men would go down then and walk into the districts. The shaft was 365 yards deep, a yard for every day of the year is how I remember it.

“It was fantastic, absolutely fantastic. I have never heard anybody that worked in Blaenserchan say that they wouldn’t go back there tomorrow. I am the same, as much as the conditions were horrible underground, as a mine could be. The atmosphere of the boys was fantastic, everyone had your back!”

There was ‘hiraeth’ in his voice as he spoke and it was clear to me that the years spent at the colliery were so important to him still.

We stopped for a little while where Phil had had his photograph taken when the colliery was still winding and both marveled at how much Nature had changed the landscape.

We both thought that the valley would be barely recognisable in a few years as the location of a deep mine.

Phil’s recollections turned to the ruined buildings nearby, which I had only thought of as the pithead baths, but I now found out that they were much more than that.

There were offices for the manager, secretaries and timekeepers and an ambulance room all located on this side of the valley, but the hub was the canteen!

“The canteen was here, at the back end of the baths. Everybody used to come and meet here in the mornings or in the afternoon to have a cup of tea before you went to work and after as well. We’d have our meetings there and it was where we got paid at a little pay booth. We were paid in pound notes then, in brown envelopes.

“There used to be the pay wagon that would go around all the pits on a Friday. There must have been thousands and thousands of pounds on it. It was just like an armoured money truck, dark blue, but smaller than the trucks today. When I think about it … how that was not robbed on this road I’ll never know! There was nothing to spend your money on here, but in some collieries the first thing the boys would have to do was to pay their tab at the pub outside the pit gates.”

Entrance to the pithead baths was very strict indeed. There were two sides, a clean side and a dirty side and the men had a locker in each side. At the end of a shift, when each man’s clothes and boots were black with coal, entrance to the baths could only be made through the dirty side. Anyone breaking this rule could face lengthy ban of a week from using the facilities by the baths attendant!

Phil has reason to remember the manager’s office very clearly. The manager could keep his watchful eye over the workings at the colliery from his large office window, a window that Phil almost smashed when he dropped his hammer on it!

As we talked I began to get an understanding that a mine was much more than a place of work, it was a community in its own right.

We continued our walk around the bend to where the pithead buildings once stood, a journey that the boys would once have made on the work’s bus and stopped to chat at the site of the downcast shaft that is marked today by a circular wall of stone and brick.

The clean air went down this shaft and there was enough room for two cages to transport men and materials. One cage operating from the top and one from the bottom, which crossed in the middle of the shaft when winding was taking place.

Phil expanded on his work as an electrician, which could take him far and wide underground. There were about twenty-four electricians at Blaenserchan, with about six electricians on a shift.

“Very often we would be working so far in that it quicker to come out by walking to Six Bells pit bottom and get a Landrover back … because we were electricians we were expected to work on kit out in the distant reaches of the workings. Horrible to walk mind you, in the damp and the dark and sometimes we’d be walking a long time with all our tools!

“The charge on your battery would normally last a shift, not a problem, but if you were working a ‘doubler’ or something like that it could start to fade towards the end of the shift. Then it would be time to adjust the settings on your lamp – dip and dazzle we would call them – dip was a shallow light, which would light up a small area around you. You would turn the lamp to dip and walk pretty slowly then!”

Photo: Tom Maloney

The time went so fast on this walk and there was so much to take in.

I don’t think that I had any real comprehension before of just what a subterranean world existed below the ground. It was fascinating to learn how connected the collieries of the valleys were.

But for me, it was the community spirit that came through so strongly in Phil’s words, how the boys took everything in their stride and had each other’s back.

Photo: Tom Maloney

Just before we finished our wander we spotted a Marbled white butterfly (Melanargia galathea) fluttering near the downcast.

I have seen Marbled Whites at The British over the past couple of years, but this was my first time to see this lovely black and white checked butterfly at Blaenserchan.

One of its little wings was damaged and frayed, but this did nothing to diminish its beauty in my eyes. It reminded me of the Blaenserchan valley itself, with its legacy of industrial scarring and yet still with so much grandeur and beauty after all those years.

Nature’s healing hands have done so much to restore this landscape to a green space once again, but it seems to me to be so important to know and understand the history of the valley as well.

I have a better understanding now thanks to Phil.

Diolch yn fawr iawn Phil!

Some of the mining terms used in the article:

The coalface – The place in the mine where the coal is cut.

District – The name of area underground where a coal seam is worked.

‘Weight coming on’ – where the roof of the mine distorts or buckles due the heavy weight above.

Rings – The oval steel rings used to support the roof of a roadway.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

A different era, but my great-great-uncle was killed at Blaenserchan in 1890. He was 12 years old and a door-opener: he fell in a pool of boiling water and took two weeks to die. The legacy of coal mining in Wales is a mixed one, at best.

Such very hard times and such a tragedy that is so very hard to take in. How your poor uncle must have suffered and how much pain the family must have endured as well. The Llanerch Colliery Disaster which was very close to Blaenserchan happened in the same year and also included the deaths of 12 year old boys. I remember the feeling of shock reading the list of names and ages. You are right the legacy of mining is a mixed one at best

This reminded me of when my father worked Blaenserchan and as a young boy I would sit in the window of my parents bedroom watching for my father to come home after a night shift. He always had a Tunnock’s caramel bar for me. They taste the same today as they did then.