The Welshman whose family history links two tragedies: the Holocaust and the Palestinian catastrophe

A Welsh Jewish journalist who had nearly 50 members of his family murdered by the Nazis is to release a podcast series linking the Holocaust with the Palestinian “Nakba”, in which Arabs were massacred in the late 1940s and had their land seized by Jews.

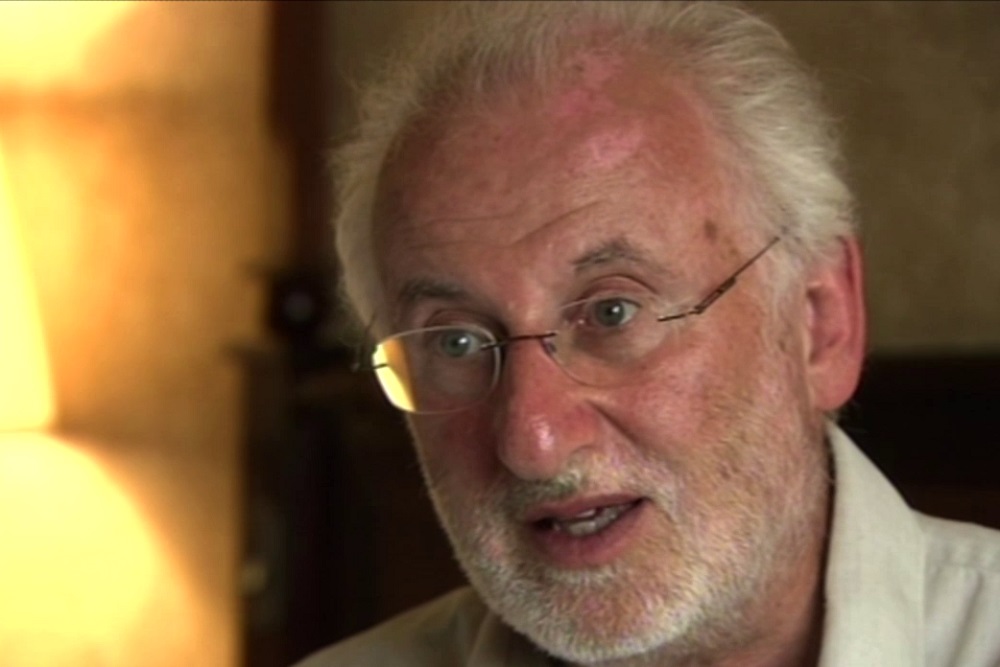

Mike Joseph, who was born in Cardiff and now lives in Pembrokeshire, is aware that many will loathe his narrative, but says that everything in the roughly 20-episode series called Keys stems from his own family history.

What he discovered was that after fleeing from the Nazis in Germany, a close relative became involved in the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians.

A video trailer for the series has now been released, while the podcasts themselves will be published weekly from September 6.

Joseph said: “I’ve been working on this for half a lifetime. I guess what started it was when the Berlin Wall came down. That was an opportunity that my mother had been waiting for all her life – to get back into East Germany to try to find out what had happened to her childhood home, and try to get it back.

“By the time the Berlin Wall came down, she was too old to do anything about it and I was a journalist. I was her son and I had some relevant skills and off I went to East Germany. I wasn’t pursuing this as a journalist – I was pursuing it as the son of my family.

“Even though there’s an awful lot of politics, an awful lot of history and an awful lot of controversy in it, it’s a family story. Everything in this story comes directly from my engagement, my research and my decades of travels, unpicking my own family story. I’ve been shocked, astonished and taken by surprise time and time again.”

Murdered

Considering the numbers of people in his family murdered in the Holocaust, Joseph said: “I know that my mother counted up in a horrible accountancy exercise how many family members she knew, or knew via her parents’ stories, by name. She counted 46. And that put some kind of horrible dimension on it.

“I’m not sure that 46 deaths are worse than one death, but they do tell you something about the scale of the catastrophe that hit central Europe and the Jews in particular, but not only the Jews, in the middle of the 20th Century. It was on a scale that people couldn’t believe at the time, that Jews couldn’t believe at the time, and the world has struggled ever since to get some idea of the scale of it.

“Partly I think we’re still suffering from that very comprehensive, nihilistic destruction in the sense that it makes it very hard to see that was sadly not the end of violence and the end of killing. Far from it – the world is a violent and bloody place, but there’s always this sort of competition to be seen as much of a victim as other sufferers. But that creates a resistance for those to whom Holocaust history is all important, and they say, ‘You can’t compare it to the Holocaust, there’s nothing like the Holocaust.’

“Well of course you can’t compare the Holocaust. You can’t compare the Armenian Genocide, there’s nothing like that. And equally, neither can you compare the Palestinian catastrophe, the Nakba. That is incomparable, and in one particular way, which is that it may have started in 1947 or 1948, but it’s still going on today.

“So every piece of history casts its own shadow, makes it in some ways easier to understand what’s going on today, and in other ways harder, because you set up these culture wars, with everybody taking a position that they defend one history and therefore need to deny another history. But that’s rubbish – it’s not like that!”

Family history

Joseph grew up in Cardiff, to which his parents had escaped from Germany as the persecution of Jews intensified in the run-up to World War Two.

Asked how he had found out about his family’s dark history during his childhood, he said: “In fragments. In that strange way in which children try to make sense of this strange world they’re growing up in – sometimes they get the right idea and sometimes the hopelessly wrong idea. You try to make sense of it in hindsight.

“One thing that Cardiff needs to know and needs to be very proud of is that it’s an immigrant city. It wouldn’t even be a city without immigrants. Everybody knows that Cardiff has had huge immigration from Ireland, from Somerset, from the Midlands, which made the city the huge coal, shipping and steel city that it was.

“And of course it didn’t stop there. As a port and the world’s greatest coaling port, it drew in sailors and people jumping ship from all over the world, including Somalis and people from Arab sheikhdoms. Literally every corner of the globe has been touched by Cardiff, both in terms of the export of coal and other minerals, and in terms of the import of people.

“The Jews came to Cardiff in two waves from Jewish communities in eastern Europe. The first was at the turn of the 20th Century. They were escaping the Tsar’s pogroms. They were escaping what was a pretty scary and marginalised life in the Russian Empire. Until the passing of the Aliens Act in 1905 that put a stop to it, people from eastern Europe, not just Jews, but people escaping poverty, Poles, Ukrainians, came to Wales in considerable numbers and founded the first substantial Jewish communities and synagogues in Cardiff.

“You can still see their main synagogue at the bottom end of Cathedral Road, a couple of doors up from the junction with Cowbridge Road. That was the Orthodox Synagogue and that was what being Jewish meant in Cardiff in the 1910s, 1920s, 1930s.

“And then came the second wave of immigration, and that was from central Europe – basically Germany and the central European states. And that included my parents. Both my mother and father arrived in Cardiff in 1939. They were not anything like the earlier generation of Russian Jews – firstly, they’d grown up in a democracy in Weimar Germany, in a place that was also ethnically very diverse. Berlin was the cultural ‘go to’ place in the West.

“They were what you might call assimilated Jews. In private, with their families, they led Jewish lives, and in public, in school and when they went shopping and so on, they were part of their cities, whether it was Munich in my father’s case or Leipzig in the case of my mother.

“But there was another way they were different from the Russian Jews, which is that 40 years later, by the 1940s, those who came from Russia were established and comfortable, and they were very alarmed at the arrival of a new wave of immigrants. This sounds familiar, doesn’t it, how one wave of immigration resents the next wave.

“Interestingly, the rabbi of the newly formed Reform Synagogue in Cardiff, who was himself a German Jewish refugee, was also a leading anti-Zionist and was an anti-Zionist all his life.

“So how did a young Welsh-born child of German Jewish refugees learn about the Holocaust? in a way you don’t learn about it, you just hear about it, because that’s what your parents are absolutely obsessed with and can’t ever ignore. It’s like the weather – it’s always there. And unless you’ve got extreme weather, you just get on with it. So I grew up both knowing about the Holocaust, because it was part of what you talked about, and also just taking it for granted. So it was a different thing to actually come face to face with it after the Berlin Wall came down.”

East Germany

Joseph said that almost his first meeting after deciding to embark on the project was with the actual Nazi who had stolen his mother’s house: “I went to see if the house was still there and instead I ran into the Nazi who’d taken the house,” he said.

“I had an argument with him. I wanted my mother’s house back and he wasn’t having any of it. He saw his position as being German. He might have been a Nazi propaganda chief, but since then he’d been accepted by East Germany, by the Communist state, as a respected elder, and been awarded the house.

“That was the start of my learning curve, and that’s what I narrate in the story – not only the story that I uncovered for my family’s history, but my own journey of ‘how do you find this out, and is it what you expected and where does it lead us’. With some of my journeys, I set out to discover one thing, and discovered another thing.”

Asked why he thought some people were likely to be offended by his narrative, Joseph said: “It probably depends who they are. It’s one thing if you’re a party politician and you’re looking for a stick to beat, let’s say, Labour with. Any stick will do, if it works. It’s another thing if you are, let’s say, a Jewish settler in the West Bank.

“The last time I had an event organised to narrate my discoveries from my research into my family history [at the National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth] was just before the pandemic. It was closed down as a result of pressure on the Welsh Government from the Holocaust Day Memorial Trust.

“Essentially they implied that I was engaged in antisemitic discourse by talking about the Holocaust and the Palestinian Nakba together. It was a claim that was accepted by the Welsh Government but not investigated in any way whatsoever. Nevertheless, the fact that that claim was made a few days before the British general election in 2019, and that Labour was absolutely terrified of any more assertions against it of antisemitism, was enough to make the matter so politically sensitive that my event had to be stopped.

“There was no sense that the merits of what I was saying were examined … or even, what I was saying. Nobody knew, nobody asked, nobody found out. To this day they don’t know. It was enough that there was an allegation, and the allegation closed down the event.

“It’s chilling – you don’t have to have any evidence, you don’t even have to have a specific allegation of an offence, It’s enough to have the fear that there may be some transgression of an implied taboo.

“And that’s one of the most effective ways of censoring, because you don’t have to put up a case, you don’t have to argue it, you don’t need evidence, you don’t need anything. It’s clearly a distraction tactic, whether it’s done consciously or simply because that is what everybody else is doing.

“The story that I narrate in Keys actually takes us not to one area where there is a conflict of historical memory – Israel/Palestine, Holocaust/Nakba – but to three. In every case, I didn’t go looking for the controversies, the controversies came and found me.

“The first one was when I go to Germany, the Berlin Wall is opened, I find my mother’s house, I find the Nazi who took it and then – what could be more straightforward – I want my mother’s house back. But I find myself opposed not only by the Nazi, but also by the German state, and its laws. So what starts as a personal effort to get some family justice ends up as an international dispute between Britain and Germany – something which I’ve uncovered recently in Foreign Office papers from the time, which reached both the Queen and the Prime Minister.

“The second one is I then go off to Ukraine to find what actually happened to my mother’s family. How were they killed, where were they killed, and above all, who killed them? And what I discover – and you’ll see immediately how sensitive this is – is that the Nazi who was responsible for killing them could not have done the killing without the active support of large numbers of Ukrainian fascist militia.

“They did the killing – and I found the evidence for that.

“But not only that: at the same time, in the same Ukrainian city, I discovered Ukrainians who had been colleagues of my grandfather before he was killed – and who had been trying to assassinate the very Nazi SS boss who had been leading their fellow Ukrainians in the fascist militia.

“In other words, there was a Ukrainian civil war going on at the time of the Nazi occupation of the Soviet Union. What a nightmare story to unpick right now, in the midst of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, where Putin likes nothing more than to call Ukrainians Nazis.

“Well, the historic truth is that there were Ukrainians who were Nazis, but there were also Ukrainians who were democrats, resistance heroes, patriots – and a struggle for the soul of Ukraine was going on. So that was the second conflict that I stumbled into, completely unaware.

“The third conflict is really very simple. I go off to Israel to find the only memorial to my mother’s murdered family. There isn’t one in Ukraine, there isn’t one in Germany, there isn’t one in Britain. But there is in Israel. I literally ran head first into the Palestinian Nakba.

“In order to mourn my grandfather and his family, I have to deal with the evidence that the other half of my family was directly hands-on involved in the ethnic cleansing of Palestine in 1948 – another part of my family story. People would think very poorly of me if I say I’m setting out to uncover my family’s story and I only uncover the one bit, and I leave the other bit in the dark. You either do it all or you don’t bother at all.”

Holocaust Museum

Joseph recalled how a guide at Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust Museum, had been sacked for telling visitors that the museum’s rooftop viewing platform was within sight of a Palestinian village called Deir Yassin, where more than 100 people were massacred by Israelis in 1948. There were other Palestinian villages where people fled for their lives when they heard that massacres were taking place elsewhere – maybe 750,000 Palestinians in total.

Joseph said: “It really is quite something to come to the world’s most important Holocaust Museum and to find that a final step of the way brings you to a viewing platform where you’re looking out over this beautiful view, with the hills around Jerusalem all covered in trees – the Promised Land.

“And in the middle of those trees are the ruins of Deir Yassin. That is what the Yad Vashem guide had mentioned to visitors and said, ‘This is something that is also part of our history and we need to understand it’ – and was sacked for that. That was just the first moment – and when I then almost the next day discovered this was not just a connection between ‘I’m here mourning my grandfather and over there there is the rubble of a Palestinian village.’

“Just round the corner was my uncle’s house, and what he did was another story. That brought me absolutely face to face with the reality of what was done in 1948.”

Asked why he was publishing the series himself rather than trying to get them onto a main broadcast channel, Joseph said: “I think there is nothing that I cover or do in my series that would not make a perfectly acceptable serious contribution to public understanding. It would be perfectly suitable for putting out on BBC, Channel 4, you name it.

“That said, to propose any freelance production to the major networks is an absolute lottery at the best of times. It so much depends on what has been decided they need to prioritise this season, and where the funds are going.

“That in itself is a game that either succeeds or in most cases does not succeed. Secondly, hard-pressed commissioning editors obviously look for signs in an initial pitch about whether a given idea or topic or format is likely to get through the commissioning process, or is it likely to stumble at some advanced stage and therefore is probably better to pass over now and look for something that’s less trouble.

“I’m sure that a pitch that I might make for this series to a major commissioner would fall into the ‘too difficult’ pile – not that it’s not worthwhile, not that it’s not valid, not that it’s produced to established principles of journalistic accuracy and responsibility and balance. No – simply that it’s too difficult.

“To make a more general point, clearly the present UK Government is looking for ways of making discourse about Palestine harder. And it’s doing so because there’s no question that the pro-Israel lobby within the Conservative Party is particularly effective and particularly strong – and does a good job of representing Israeli Government views within UK Government circles. So on this particular topic there is pressure, and it has been brought to bear.”

Finally Joseph wanted to make a point about what he sees as the degradation of the word “antisemitism”. He said: “Antisemitism meant something when my mother was expelled from her childhood home in 1938 and when my father was sent to Dachau for a few months before being released and expelled. Antisemitism was what happened to Jews on the streets in Germany in the 1930s. They got beaten up, expelled and then mass-murdered.

“Today the claim of antisemitism has been robbed of its meaning by being used as a catch-all for anything that has a whiff of criticism of the Israeli Government. That would have appalled both my parents – and they were both Zionists.”

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Sounds as if it will be an interesting if horrific story. I wonder if pressure will be applied to the hosting company to stop its publication.

I went to Israel in 1995. As I observed the young men and women in Yad Vashem wearing army uniform and carrying machine guns I was immediately struck that what was going on in modern Israel had a great deal of similarity to what had happened in Nazi Germany and I couldn’t understand how it was being allowed to happen again!

Such an interesting story! I was born in Vienna in 1936, escaped to Northern Ireland in 1938 and was lucky enough to attend Cardiff High School for Girls and UCNW Bangor before emigrating to the US. I wonder if the Joseph family knew the Schenkel family who lived on Dan-y-Coed Road in Cyncoed.