Colonialism, genocide, and the UK-Rwanda deal

Sophie Buchaillard

Two years have passed since the UK Government first announced its migration and economic development partnership, a controversial scheme to deport male asylum seekers who illegally crossed the channel, 40,000 miles away, to a country with which they have no ties, in exchange of financial investment.

As Parliament breaks up for the Easter holiday this year, the legislative ‘ping pong’ between the Commons and the Lords remains unresolved, following a Supreme Court ruling which found that Rwanda was in fact not a ‘safe’ country for the purpose of the scheme, leading the government to legislate to compel the courts to treat Rwanda as a safe destination, and ignore some of the fundamentals of the refugee convention.

The Supreme Court’s main objection was indeed that Rwanda’s domestic legal system did not guarantee non-refoulment, a cornerstone of the refugee convention, enshrined in UK law, which prevents those seeking asylum from being returned to a home country where they might face torture, persecution or death.

Genocide

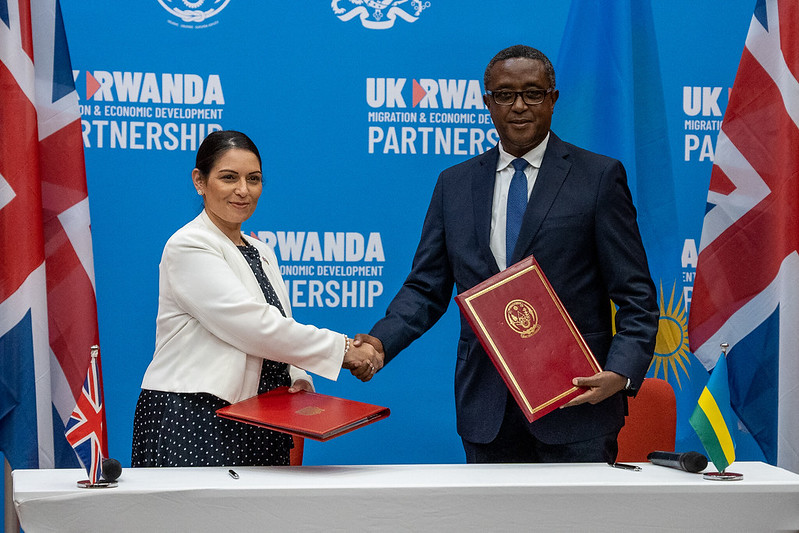

Two years on from the initial deal, and as Rwanda is about to commemorate 30 years since the genocide of the Tutsi, I am reminded of the symbolic significance of Former Home Secretary Priti Patel’s trip to Rwanda during the 2022 commemoration, her presence inscribing the visit within a very charged colonial context.

Rwanda is a country familiar with the dangers of categorisation and the use of dehumanising language.

When the kingdom of Rwanda first became a German protectorate in 1885, it had a complex ruling structure, semi-feudal and supported by an administrative network that oversaw three groups of people – Tutsi, Hutu and Twa – organised in province, district, hill and neighbourhood.

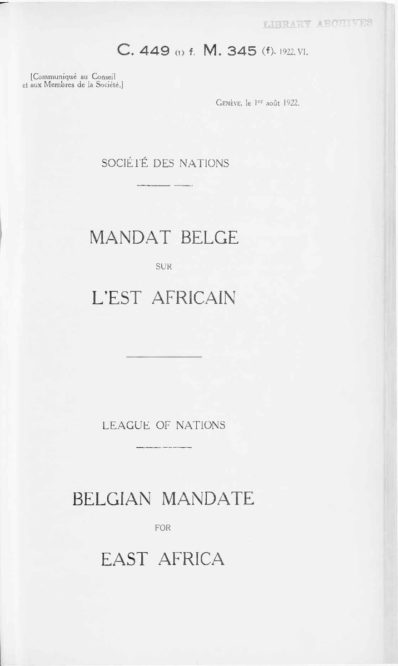

All three groups shared a language and culture. After Belgium was given mandate to rule over Rwanda by the League of Nations in 1923, those traditional structures were eliminated, replaced by forced labour.

Harmony

Following a census in 1933, Belgium then introduced identity cards that categorised each Rwandan as Hutu or Tutsi (and a minority of Twa), importing a racial interpretation that mirrored the division between Dutch-speaking Flemish and French-speaking Walloon in Belgium.

This division was manufactured and enforced by the Belgians. Hutu and Tutsi had previously lived in cohesion and harmony, within a sophisticated administrative system where the terms Hutu and Tutsi referred to land and cattle ownership and were therefore fluid.

In effect, Belgium engineered an ethnic interpretation, creating a divide which extremist Hutu would use sixty years later to justify genocide in 1994. As part of the 1961 independence, the Rwandan monarchy – composed of Tutsi – was deposited and replaced by a Hutu one-party system.

The extremist Hutu started their campaign against the minority Tutsi shortly after, building on the feeling of resentment experienced by a majority of Hutu who felt exploited by those who had benefited under Belgian rule.

The growing propaganda against the Tutsi built via government-run papers and radio stations.

Cockroaches

The term Inyenzi – which means cockroaches in Kinyarwanda – was used to describe the Tutsi, while the extremist Hutu developed a narrative of ‘Hutu Power’ to roll back those they described at home as ‘foreign invaders’, an ethnicist narrative first articulated by the British colonial agent and explorer John Hanning Speke in the 19th century.

Speke presupposed that the Tutsi had an ancestry outside of this part of Africa, on account of their ‘European features’, an argument which was reinforced under German and Belgian rule, two countries with very racialised world views of their own.

Strategic buffer

The systematic campaign of disinformation at home was supplemented by a rhetoric directed towards international partners who saw the importance of the geographical position of Rwanda in the Great Lakes region of Eastern Africa.

After Rwanda gained its independence, France worked to develop strong links with a country it saw as a key player in its post-colonial policy.

Due to its position, Rwanda represented a strategic buffer, providing a line of demarcation between francophone and anglophone zones of influence in Eastern Africa.

The special relationship between France and Rwanda was bought with limited financial investments and encouragements for Rwanda to democratise itself.

Influence

In Paris, Rwanda became the tip of a new policy of international relations with former francophone colonies aimed at maintaining France’s area of influence on the African continent.

President Habyarimana of Rwanda played on this eagerness, obtaining weapons from France to arm his extremist government against those the President misrepresented as ‘English-speaking invaders’, activating Paris’s fear of losing ground against its post-imperial anglophone competitors – Britain and America.

The people Habyarimana sought to fight were in fact Tutsi exiled from an earlier wave of violence that had taken place in 1973, and which coincided with the coup d’état that had brought him to power.

Killings

Two years after Rwanda’s independence, European journalists already described killings of Tutsi in Rwanda that echoed what Europe had experienced during the Holocaust.

By the 1990s, a number of neighbouring countries had offered to broker a deal between the parties, in order to set up a representative government in Rwanda and diffuse tensions. The Arusha Agreement was signed in 1993, after France applied pressure on Habyarimana.

A few months later, his plane was shot down over Kigali, marking the start of a hundred days during which 800,000 Tutsi and moderate Hutu were murdered and mutilated. After three months, the extremists were rolled back by the same forces Habyarimana had so feared, led by Paul Kagame.

The relationship with France rapidly deteriorated from that point, with President Kagame, now in power, accusing France of having contributed to the genocide by supporting the génocidaires – those Hutu extremists who committed the genocide – providing logistics, training and weapons, as well as safe passage for the perpetrators who escaped to the refugee camp of Goma in Zaïre under what is known as France’s Operation Turquoise.

Realignment

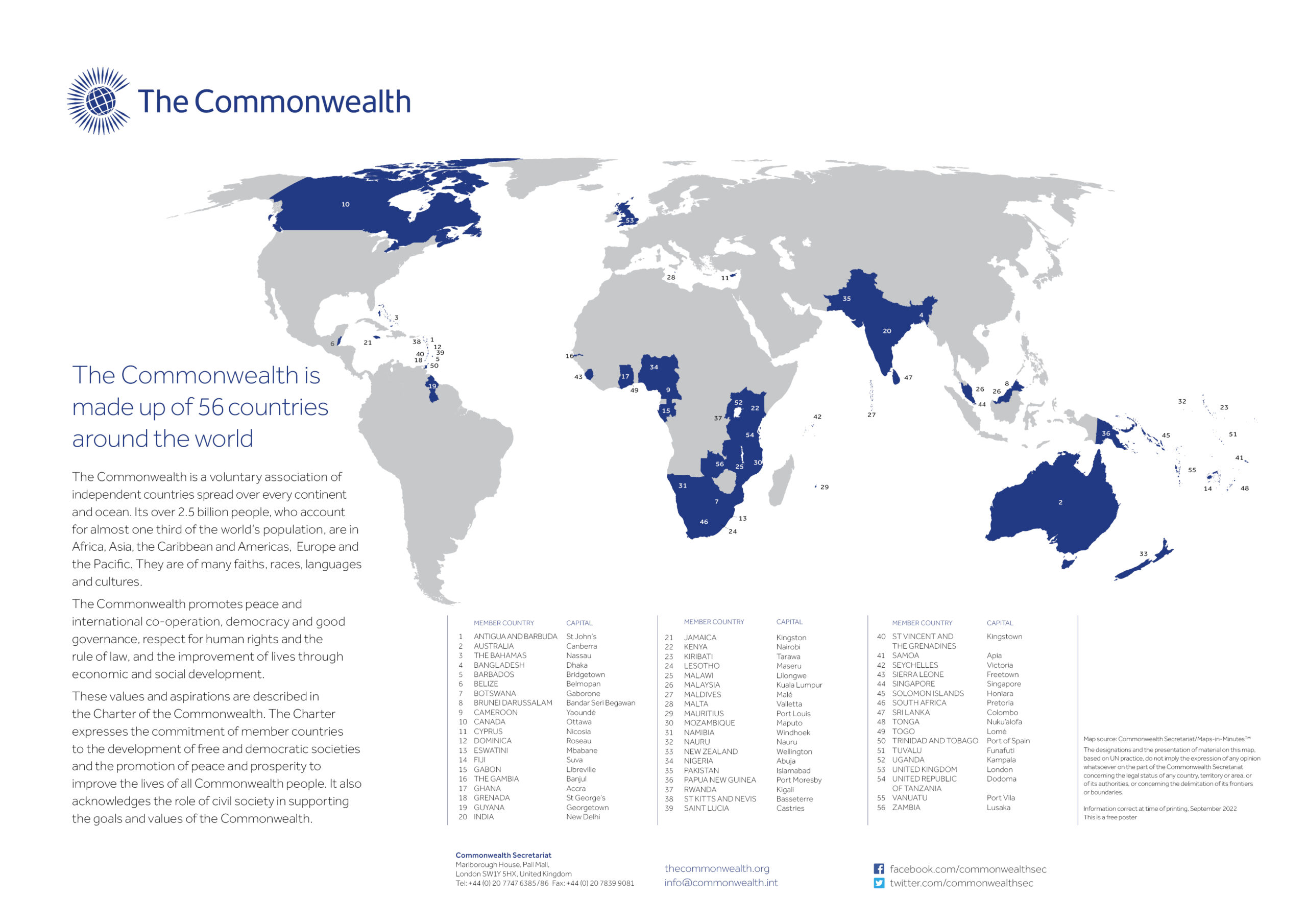

In 2009, Rwanda became a member of the Commonwealth, only the second country, after Mozambique, to join without any historic, colonial, or constitutional ties to Britain.

The decision represents a symbolic realignment towards Britain, via an organisation that most will associate with the former British Empire.

Not long after, French President Emmanuel Macron tried to mend bridges with Rwanda by commissioning a review of the role of France in the genocide of the Tutsi, lifting a fifty-year seal on the official archives.

On 26 March 2021, the French Commission of Research on the Archives Relative to Rwanda and the Genocide of Tutsi presented its report.

Genocide

The document is 992 pages long. It addresses both the question of the role and engagement of France in Rwanda in the run-up to the genocide and of responsibilities that are political, institutional, and intellectual in nature, but also ethical, cognitive, and moral.

It explores the almost schizophrenic way with which the French Government of President François Mitterrand sought to encourage the democratisation of Rwanda throughout the 1990s, whilst at the same time providing the extremist government with extensive military support in response to a mythical foreign threat coming from English-speaking Uganda and understood by France through an ethno-nationalist prism reminiscent of colonialism, projecting fears of losing a foothold on France’s area of influence in Africa.

The report states that ‘this conception gradually spread through the ministries as well as the central administrations between 1990 and 1993, even if the analysis of the precise nature of the military threat posed by the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) varied according to the services and the advisors. In October 1990, this threat was qualified as “Ugandan-Tutsi”.

This expression is frequent in the archives and reveals the French authorities’ ethnicist interpretation of Rwanda.

This conception persisted and fuelled a way of thinking where, given the Hutu majority, the possibility of the RPF victory was always equated with an anti-democratic takeover by an ethnic minority.

Imperial power

The 2021 French report is a rare act of reflection by France on what could be considered part of its colonial past, one that highlights the inherent contradiction between France as the country of Les Lumières, and France as imperial power.

The report condemns the French Authority of the time for their continual blindness, and for supporting a racist, corrupt, and violent regime, conceived originally as a model for what France hoped would become its postcolonial policy in Africa.

France ignored the warnings coming from Rwanda’s (anglophone) neighbouring countries, and from some of its own civil servants, who were marginalised for their efforts, failing to fight extremism and neglecting to encourage a policy of deracialisation.

Instead, it armed the extremist party militias who would go on to commit the genocide.

On France’s ethnicist reading of the situation in Rwanda, the report writes that ‘this perspective corresponded poorly to the Rwandan reality given that the country’s political and social resources were resistant to the influence of ethnicization.’

The report adds that ‘ethical responsibilities regarding political action call into serious question the decisions made at the highest level that misunderstood events even when all the information was available’, further adding that there is also a cognitive responsibility when a country fails to realise that its ethnicist reading ‘repeats a colonial pattern’.

Colonionalist meddling

It is in this context that Priti Patel chose to journey to Rwanda in April 2022, the month in which the country commemorates a genocide that illustrates the culmination of colonialist meddling and dehumanisation.

Her decision also coincided with the fact that President Paul Kagame hosted the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting a month later. For Rwanda, both events signalled a historic break from the past, as well as presenting opportunities for strategic investment.

Signing the ‘world first’ migration and economic development partnership in the month of April placed the focus firmly on the future in a month synonymous with the 1994 genocide.

Imbalance

On the 14th of April 2022, the day on which Priti Patel and the Rwandan minister for foreign affairs and international cooperation Vincent Muruta signed the initial agreement, the English-speaking Rwandan newspaper The New Times printed a statement from the Rwandan government that celebrated the ‘bold new partnership and innovative approach to the global migration crisis’ that would ‘address the imbalance in global opportunities which drives illegal migration’.

At the same time, however, a paper in Kinyarwanda, Kigali Today, reported on a picture of Priti Patel kneeling, eyes downcast, whilst laying a wreath in front of a huge sign commemorating the victims of the genocide, a gesture which would have been interpreted in Rwanda as an act of contrition, a subtle acknowledgement of the wrongs of the past.

Shift

In the UK too, this event marked a shift of sorts. The UK and Rwanda Migration and Economic Development Partnership, as it was named, came only a few months after Britain released a statement to the United Nations in January 2021, a statement in which it had expressed concerns with ‘continued restrictions to civil and political rights and media freedom in Rwanda’, recommending that ‘the country conducts transparent, credible and independent investigations into allegations of extrajudicial killings, deaths in custody, enforced disappearances and torture, and bring perpetrators to justice; protects and enables journalists to work freely, without fear of retribution, and ensure that state authorities comply with the Access to Information law; and screens, identifies and provides support to trafficking victims, including those held in Government transit centres.’

What can we infer from the UK’s sudden change of perspective?

Asylum rules

Part of the 2022 National and Borders Act, the Rwandan deal was one of a series of significant changes which drastically affected asylum and citizenship rules in the UK. Prior to its introduction, in 2021 there were 48,540 applications for asylum in the UK (not including dependants), mostly from places of conflict like Afghanistan, Iran, Eritrea, and Pakistan.

The decision to grant refugee status was made by a court and in case of refusal, people were expected to return to their country of origin.

Prior to the Rwandan deal, some would have returned on a voluntary basis, and anyone willing to do so may have been eligible to apply for assistance via schemes of assisted return.

Otherwise, the Home Office would have enforced removal from the UK, except when it was not safe for the person, in which case the applicant would be allowed to remain in the UK until conditions in their country of origin permitted a safe return.

Following the Illegal Migration Act passed in 2023, anyone who travels to the UK outside of agreed channels will never have their claim for asylum considered.

Instead, a categorisation has been introduced, with asylum seekers who enter the UK illegally being criminalised. One of the effects of such a measure is that it undermines current protections against the same modern slavery the Rwandan deal is supposed to prevent.

The new law also gives the Home Secretary the power to strip British nationals of their citizenship, provided they hold another passport, a measure reminiscent of World War Two.

Economic argument

Over the same period, opposition to the scheme seems to have shifted from a moral to an economic argument, since in addition to the £370 million the UK already paid Rwanda, every person relocated would cost the UK tax payer £151,000. What seems to have waned is considerations about the human impact of moving traumatised people to be processed in a third country, despite reports about the detrimental effect of similar schemes in countries like Australia.

We know such policies have a net dehumanising effect, with long term impact. Yet, in April 2022, the official statement printed in the Rwandan press referred to the human capital investment the UK would inject into the Rwandan economy with this new deal.

It is hard not to draw a parallel between the UK providing human beings as ‘investment’ for its new partner and the sort of human trafficking this deal is claiming to address.

Illegal migrants

The deal is in effect treating human beings like goods and commodities, a phenomenon the effect of which is well documented.

Writing in 1961 about France’s former colony of Algeria for example, the psychiatrist Frantz Fanon catalogued the consequences of a similar logic on his patients, observing that a form of historical trauma happened amongst the victims, when the horror of an initial event was compounded by the discrimination and oppression victims continued to experience, and which impacted subsequent generations.

Yet, familiar patterns have re-emerged, enshrined in law by the Safety of Rwanda (asylum and immigration) bill, and the introduction of an Illegal Migrant Act.

At first glance, the deal came in response to Emmanuel Macron’s apparent failure to stop illegal migrants boarding dinghies to cross the channel to Britain.

In practise however, the diplomatic ping pong that has taken place between both sides of the channel seems symptomatic of broader dynamics, and in particular a fragmentation of democratic principles we once took for granted.

Brutal

Whilst the UK government pledged an additional £460 million over three years to the French in order to prevent the illegal crossings before they take place, in France the riot police now applies a “zero-fixation point”, preventing refugees from settling anywhere, destroying their meagre belongings, and blocking access to food and water.

In a recent article in The Conversation, Sophie Watt describes her time in the wild camps on the French side of the border, where Every evacuation is brutal and dehumanises the refugees a little more, concluding that rather than act as deterrent, these policies only encourage further crossings, as traumatised refugees run away from the violence and lack of hospitality at the French border.

We are witnessing a resolute shift towards a disregard for human rights, a manifest re-drawing of lines of influence around economic treaties, and a tendency towards national preference principles reminiscent both of the colonial era and of the sort of dehumanising narrative choices which, thirty years this year, led to the genocide of an artificially categorised group of people in Rwanda.

This is an updated version of an article originally published in the ByLine Times.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

40 thousand miles (the circumference of planet earth)?

The distance from Cardiff to Kigali is only 4,167 miles (airport to airport)!

Yet another sad day for the British and its Government.

Tories will seecitcas a way of making money by spebing our taxes!