Decoding the Russian view on Putin’s reign

By Matthew G. Rees

“In Russia, we also have a bear. And sometimes it can be very dangerous.”

The speaker was a small, quiet, dignified woman of perhaps late middle-age, with neat, short hair and eyes that were serious.

Whether because of widowhood or religious orthodoxy, she wore black… save for a silver crucifix (whose size to Western eyes might have seemed large), which hung brightly from a finely linked chain around the collar of her sweater.

In the absence of her regular, Russian teacher of English, I had gone to tutor her in a neighbourhood of the type generally described as an embassy district – properties of an older and larger kind, set in quiet streets that had greenery and – I suspect – money (not that I ever saw very much of that) – close to the centre of Moscow.

In a room (which we alone occupied) that overlooked a garden, the woman’s eyes held mine for a moment as, speaking softly (and somewhat shyly, it seemed), she made her remark about the bear. With it, came a faint but perceptible nod of her head.

I can’t remember now how our conversation came to take its ursine turn. I suspect that I may have been using photographs as prompts for a dialogue. Her English was very good. Our discussion moved on to other things.

Whether her observation had been a matter of mere zoology – or something more – I didn’t know. I still can’t be sure, several years later.

A kind of code

One thing my travels have taught me is that, when it comes to expressing dissent, those who live in authoritarian societies tend to resort to a kind of code, particularly in the matter of opinions.

Hence my present scepticism towards reports of widespread high support in Russia for Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine.

A survey in the street of their attitudes to his so-called ‘special operation’ would, I suspect, see Russians respond in the way that they thought was expected of them.

The same would probably happen if they were questioned by a researcher over the phone. (This ‘auto response’ occurs in all societies, to some degree. Think of people wandering innocently in UK shopping precincts, pounced on by TV crews compiling reports about “public reaction” to some issue of the day.)

On the surface, therefore, it can seem as if there is near-unqualified approval for Putin’s actions. In private, different answers, perhaps of the coded kind, would, I suspect, be the real responses of many.

I simply can’t imagine ‘my’ lady in black (with her crucifix and her comment about the bear) cheering-on Putin’s aggression. Likewise, other Russians who I knew or encountered: in education, engineering, medicine and law.

Their feelings would, I think, range from outright opposition, to scepticism, to embarrassment. In my mind, I hear them chorus: “But, in a country like Russia, what can we do?”

Mass meeting

For a decade or more, liberties that came with the fall of Soviet communism have steadily been squeezed from Russian life. Through it all, an increasingly autocratic Putin has been emboldened by the fuel-dependent nature of the chancelleries of Europe.

I remember the response of his regime to one protest – at a time when demonstrations were – just about – still legal (albeit subject to the granting of official approval).

I’d heard that a mass meeting was to take place in Moscow’s Pushkin Square: a protest against the escalating repressions of Putin and his government.

On finishing work for the day, I set out for the square.

Having spent ten years of my life as a journalist on newspapers in the UK, I felt this event was something that I couldn’t ignore, even if I didn’t plan to write about it (beyond, perhaps, some personal correspondence).

Pushkin Square takes its name from the writer considered Russia’s greatest poet. A statue commemorates him at its centre, unveiled in 1880 by Turgenev and Dostoyevsky.

The locality is rich in associations with Arts figures, as well as cultural and educational institutions. Mikhail Bulgakov – the prominent pre-Second World War writer (who was born in Kyiv) – is one who had an apartment nearby.

Civilians, protestors

I walked the pavement on the left side of Tverskaya Street, an always-busy boulevard, which climbs gently from Red Square, the Kremlin and Lenin’s mausoleum ‘down below’.

The vehicles I increasingly saw weren’t the usual dark-windowed Mercedes, BMWs, high-end SUVs and four-wheel drives of everyday encounter in Moscow’s wealthier quarters.

Tverskaya Street – or that section of it, at least – was instead undergoing occupation by the vehicles of the ‘security forces’: large grey-green lorries and fleets of buses.

Not service buses but military and police coaches, full, so it seemed, of personnel. Finally, here and there, the more usual kind of police prowl car.

After perhaps a mile, I came level with the entrance to the square. Or at least that point where the entrance should have been. Police and military vehicles had been parked in a column across its mouth.

All the while, buses were disgorging men and women in helmets, visors, boots and heavy-duty flak jackets of the same sludge-green shade as the vehicles in which many of them had arrived.

Although I couldn’t see into the square, people – civilians, protesters – were there. I could hear them.

Above the traffic and the trudge of the State’s enforcers, came a man’s voice – rather faint, but audible – in the wavering crackle of a microphone.

Was it Navalny (the opposition leader now in prison after a suspected poisoning attempt on his life)? I can’t say with certainty. Perhaps it was him.

Suppress and arrest

As discreetly as can be done, when gloves have to be removed and pocketed (mine being an old and bulky pair from my motorbiking days), I attempted some photographs with my phone. Unfortunately, the hasty, snatched nature of my attempts rendered them worthless.

Amidst the ever-growing numbers of police, I now noticed a young woman. She was kitted in the full, paramilitary gear: helmet, visor, flak jacket, trousers, heavy boots. She was small – barely the height of the shield that she carried before her. Her face suggested that she was perhaps still in her teens.

How sad – I thought (and still think) – that this young woman, coming past me, armed and cloaked as if for war, was being sent to contain (and, if need be, suppress and arrest) her fellow citizens, a good number of whom, I suspected, would have been her own age.

The wisdom of me staying at my vantage point seemed questionable. Although I’d never previously felt any direct hostility from the police (beyond an incident involving an off-duty officer), the presence of a foreigner such as myself (visa and accredited employment notwithstanding), hanging about on the edge of such a protest, might have been deemed unwelcome.

Judging that there was nothing to be gained from my possible detention, I made for a metro station and a train ‘home’ to my Soviet-era flat well beyond the tourist zone… as the forces of Putin’s fast-developing police state continued to pour past me.

Ominous weaponry

As the year wore on, the protests in Moscow continued. Those objecting to the regime’s policies wore white ribbons on their lapels.

Come May, I was intercepted on Tverksaya Street by two young women, who were distributing ribbons of a different kind.

The lengths of orange-and-black fabric they were offering were, I knew, for the upcoming commemoration of the defeat of Nazi Germany in the Second World War – a yearly event in Moscow’s calendar when weapons and vehicles, mainly of an older type, are driven down the street towards Red Square… where rather more ominous weaponry of the current day is sometimes seen, complete with flypasts and mass marching of the kind customarily associated with North Korea.

After thanking the young women for their gift of a ribbon, I asked them about the significance of the small strip of cloth. They immediately told me it was to celebrate Russia’s defeat of the Nazis (with the emphasis on Russia… and Russia alone) in the Great Patriotic War.

‘And the victory also of Britain, America and the other Allies?’ I ventured.

My remark drew puzzled looks (as I had – to some extent – anticipated).

For when it comes to the Second World War, many young Russians seem to know nothing of the roles played by countries other than the Motherland in Hitler’s defeat.

For them, the Western Front seems not to have existed, likewise North Africa and the Pacific. Inconvenient historical facts such as the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of non-aggression between the Soviets and Nazi Germany have been airbrushed by officialdom.

This, in part, is why – along with the forced closure of independent media and the murder and imprisonment of dissident politicians and journalists – some in Russia (but by no means all) believe and support Putin and his war.

Toppling of tyrannies

Television footage of events such as the recent concert at Luzhniki Stadium suggests to me that those in their teens and early twenties form a large contingent of his admirers. Youthful pride in the Motherland is perhaps to be expected. But I suspect that some rather twisted teaching has also played its part.

For now, the highly influential Russian Orthodox Church – in the form of Patriarch Kirill – seems to be supporting Putin, who, having apparently been a non-believer, has increasingly positioned himself close to the Church and its traditions.

Its power and prestige have, it seems, been reinvigorated. Kirill, so I was once told, has a government-issue blue light (of the police variety) for use on his limousine – to beat the capital’s often chaotic traffic.

And then, of course, there are those who in revolutions elsewhere have come to be called “the dead-enders”: people who, if Putin falls and things get bloody, will have nowhere to go amid the often-summary justice that history has shown tends to be part of the toppling of tyrannies.

This rather curious element includes extreme nationalists and sycophantic celebrities. They can be counted upon to sing their master’s praises to the very last. Their fortunes depend on it.

Which brings us to their emblem – the Z.

No such letter exists in the Cyrillic Russian alphabet. And it stands at the very end – the cliff-edge, it could be said – of the English one.

It’s as if there’s no language left… no words that can be mustered… to describe the moral bankruptcy of what Putin and “his gang” (as a Russian friend of mine once called them) have done.

© Matthew G. Rees, 2022

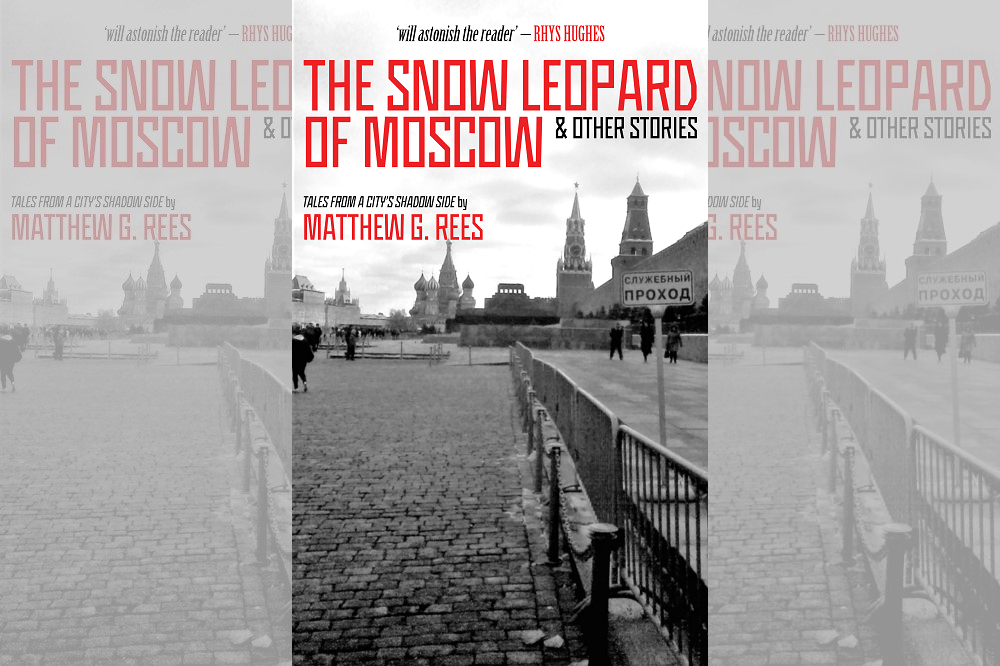

Matthew G. Rees is the author of the newly published The Snow Leopard of Moscow & Other Stories, a collection of short stories set in Putin-era Moscow.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Thanks for sharing your experience, what a shame it is that history is so fragile, I think I know what you mean about Navalny…the choices made by him and Zelensky are almost beyond western understanding, except perhaps by Assange awaiting Patel’s signature…

Will Liz Truss put her department where her mouth is, and get our lads home…round up Putin’s daughters and do a swop…

Where is Gonzalo Lira?

Gonzalo is now safe, though not allowed to leave Karkov. Was picked up by SBU, held for some time, had phone and computer confiscated, but not physically harmed (he has dual US and Chilean citizenship), or “disappeared”.