Denying the right to speak Welsh in Westminster is a form of coercive control

Niki Jones, counsellor who works with survivors of abusive relationships

Language is a complex construct, and for most of us, it’s just a way of forming thoughts and communicating these with others.

Whilst communication is an important aspect that language serves, it also forms a huge part of our cultural identity, our history and heritage.

Just like our DNA holds all our genetic material that can help trace our roots, language is a cultural equivalent. It holds historical and cultural material of entire communities going back millennia.

It helps us communicate certain feelings, the intensity of which can only be expressed and understood in the context of a particular language and the history of its people.

Multi-lingual speakers often find that there isn’t always a literal translation to many words in their language. For instance, Hiraeth in Cymraeg is loosely translated to deep longing for one’s homeland. In reality, the intensity of the translation doesn’t even come close to what the actual word means.

Language helps us develop empathy for the human condition within cultures. It helps us connect beyond just words and is key for us to be able to create meaning in our world.

As an added benefit, research suggests that being multi-lingual reduces the risk of Alzheimer’s. It helps us form emotional connections with others as well as with our own selves.

To stop someone from speaking a language of their land restricts that freedom and is akin to oppressing their voice. It also is a form of coercively taking control and denying someone their human autonomy.

This sort of practice is not new within an imperialist regime. Many ex-colonies would tell you similar stories. Even in Wales, the Welsh Not is a classic example of this sort of language oppression.

Anglicisation

Anglicisation of place names, stopping people from talking in their own language in their own country to this day, creating fear in people around communicating in their own language to the point there is an internalised fear-fuelled resentment for it, are very common occurrences.

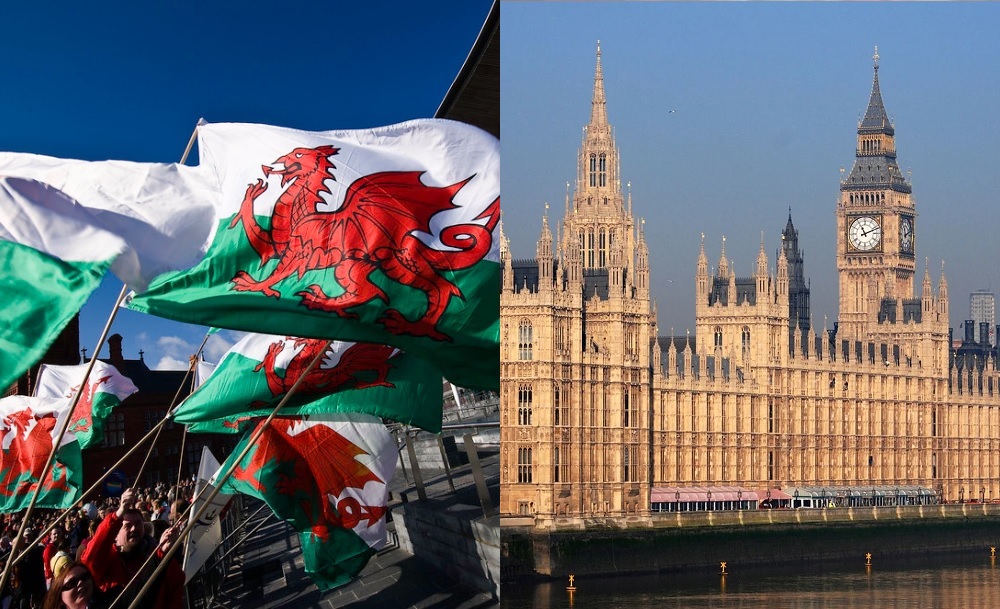

Moving on to more recent events, there was quite a lot of outrage from Welsh communities when MP Liz Saville Roberts was cautioned by the Speaker, Lindsay Hoyle, for speaking ‘too much Welsh’ at the UK Parliament.

Whilst Unionists such as Jacob Rees Mogg completely othered the Welsh language by calling it ‘foreign’, it beggars the question, how could a country be united as one when the language of one of its ‘parts’ and with that its cultural identity is blatantly alienated?

This creates a culture of exclusion and further oppression of other nations that don’t speak English as their first language. Ironically, we are sold the ideology of oneness like our lives depended on it, but the actions to reinforce that ideology reflect a starkly different picture.

This exclusion is further reflected in the status of the native language of being referred to as ‘foreign’ on the UK Parliament website. How could Wales be one with the Union, but its language be othered? The paradox doesn’t stop there.

Welsh is often claimed to be a dying or even a dead language, yet recent data shows it’s one of the most learnt languages over the lockdown and the fastest growing language in the UK.

It is common knowledge that many Welsh speakers will have moved to other parts of the UK, but they don’t have an option to say they speak Welsh on the Census unless they live in Wales.

Dying language

How could we possibly claim Welsh is a dying language when we don’t even have an accurate data available on how many people across all of UK actually speak it?

There are far too many countries in the world where there are more than one national languages. India, for instance, has 121 languages, yet not one of them is listed as a ‘foreign’ language.

Here lies the problem of incompatibility, when we accept parts in others only if they suit our own agenda, we can never truly be united because it causes a problem of inequality which by its very nature is discriminatory and oppressive.

Furthermore, these rare occurrences of the more blatant form of language discrimination don’t quite reflect the more prevalent and deeply problematic microaggressions that are experienced by bi-lingual speakers in this country.

For instance, fervent opposition of normalising Welsh language in schools, being told by strangers in public areas to not talk to your own relatives in your own language in your own country, inaccurate representation of the language prevalence by conveniently restricting it to regional forms on the Census.

Speaking your own language in your own country is not an abnormal phenomenon. However, being forced to not speaking it or being reprimanded for speaking it is demeaning, disrespectful and oppressive.

Something many Unionists haven’t realised is that a successful union is not formed out of erasing the identity of one of its part but celebrating the uniqueness each brings to truly become something that’s equal, inclusive and be proud of.

If this is the way a case for the British Union is being made, then its deeply flawed and is doomed to failure.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.