Football on the edge of nationalism: Wales and Athletic Bilbao

Stuart Stanton

There has been a recent upsurge in written comment concerning the status and future of the Welsh Language, the future of Wales within Brexit and – perhaps overdue and most intriguing of all – the continuing identity of a Welsh ‘football nation’.

Without wishing to distil the life of the nation as a whole into the proverbial pint glass of a football match, it is pertinent to consider developments in the Basque Country – Euskadi Herria – where a bilingual population of just over 3,100,000 (so similar to Wales) express themselves within Spain and Europe through the success of their major football teams, in particular Athletic Club Bilbao.

The history of Athletic Bilbao from its late Nineteenth Century foundation by primarily English engineers working the developing heavy industries of the Bilbao region – is well documented by Jimmy Burns in ‘La Roja: A journey through Spanish Football’ (London 2012).

Burns has the great advantage of being a native Spanish – though not Basque – speaker and possibly an even greater one in having his nascent football career ended by a thumping tackle from a Basque schoolmate – Mendizabal – when just seven years of age.

That one tackle becomes the author’s keynote for describing the pride and passion of Spanish, and more pertinently Basque, football.

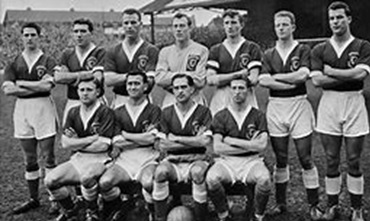

Of the various oddments and tokens we mostly care to decorate our living spaces with, one that resonates with myself is that of the Welsh football team, taken at their final qualifying match for the 1958 World Cup.

The image is well-known and popular today, propelled partly by the success of the counterparts in Euro 2016 but the feature I find so revealing is the geographical homogeneity of the players.

Swansea boys dominate, the Charles brothers, Kelsey, Jones et al., with the Wrexham borderlands contributing Stuart Williams, Hewitt and Vernon and the Valleys adding most of the rest, including the Captain, Dave Bowen of Maesteg plus the Manager, Rhondda’s Jimmy Murphy. Wales were indeed ‘Welsh’, through and through.

This team of footballers unconsciously laid down a template for what was to follow. The fortunes of the four Welsh clubs playing in the main English leagues fluctuated season-by-season reaching extremes of success on isolated occasions with only Swansea City winning a major national trophy, the League Cup in 2013.

This triumph however was managed by a starting line-up comprising one native-born Welshman, Ben Davies; another with a heritage link in Ashley Williams and a mixture of Spaniards, Dutch and Germans plus a South Korean, four Englishmen and a Danish manager.

On the surface, the team’s statement was one of a multiculturalism that sounded in harmony with society as a whole and one that was applauded by Welsh Society. Certainly, the tens of thousands who lined Swansea’s streets to welcome their heroes back displayed all the pride and passion one would expect of a celebrating Welsh crowd.

It was very different from the return home by Mel Charles from the 1958 World Cup to be greeted by a cheery remark reported as, ‘Been on your holidays, Mel?’ from the rail station ticket collector.

Unlike Wales, the Basque Country has never been represented by a recognised national team. John Toshack, highly regarded there following his time as manager of Real Sociedad (San Sebastian), arranged a ‘no-cap’ one off game between the two at Bilbao on 21 May, 2006 regardless and an intriguing event it turned out to be.

Ryan Giggs captained Wales with a youthful Gareth Bale on the bench. For the home side, Fernando Llorente, later to be a Swansea talisman, led the attack as they pressed for a winner but that came from Giggs after “collecting the ball in his own half and setting off on a trademark mazy run”.

The exercise was not to be repeated but it remains of no little importance as more and more ‘nations’ – the latest being Gibraltar – crave and receive international recognition.

Parallel

The particular effect of modern Spanish political history upon its football clubs and regional identities is dealt with in great detail by Burns. He does recognise the singular importance of the Basque Country within this and indeed the early chapters of his book are largely dominated by Athletic Bilbao both on and off the field.

The reasons for the club’s most important philosophy – that it only be represented by players either native to the area or with the strongest familial links – are clearly identified.

Arguably, in its earliest decades, there was no need to import players at all for the locals were so strong they were in surplus to requirements. This was represented by the foundation of Atletico Madrid by Basque exiles and the wholesale adoption of the same playing strip.

The only significant change to this identity came along in post-Franco times with the retention of a Spanish name, opposed to Bilbao’s reversion to ‘Athletic Club’.

One can interpret the parallel threads of modern Basque and Welsh nationalisms in a number of ways. Perhaps most obviously the violent and threatening campaign orchestrated by the ETA movement in the later years of the last Century and the resultant loss of life by almost 1,000 people has no resemblance to anything organised in the name of the Welsh nation.

Yet, it must be said, the symbolism of ‘Fire in Lleyn’, Treweryn and Road Signs remains huge in the nation’s consciousness and readily quoted when triggers are required to fire emotional outpourings.

The naïve comparison of football teams as standard bearers in a whirlpool of sentiment is perhaps not as simplistic as it seems on first sight. The YouTube channel connected to Athletic Bilbao contains several vignette films that explain the importance of the club’s players policy – unique among the major leagues of Western Europe – and the economic methods by which it sustains this.

In very straightforward terms; sell the goalkeeper Kepa Arrizabalaga to Chelsea in Summer 2018 for around Euros 80,000,000, bank the money to be used for club development, promote another Athletic produced player into the first team. There is, of course, no other option.

This economic model, defined by its cultural superstructure, cuts right across neoliberal standards where the market is controlled by prices. It is interesting, in Welsh sporting terms to compare it with rugby and the so-called ‘Gatland’s Law’ that purports to insist on Welsh players who play for Welsh clubs having prime claim on international selection.

Unlike Athletic’s definers, there is no precedent history to support this. Prior to the introduction of professionalism into Rugby Union in 1995 only a handful of players represented English clubs; and vice versa. In summary Gatland’s ‘Law’ is probably what Gatland says it is and nobody complains just as long as the team keep winning.

The ‘edge of nationalism’ referred to in the title of this contribution is a concept that pleads study and definition in these uncertain times. Commentators can be criticised as condemning the whole idea of ‘nationalism’ as something prehistoric and dangerous, an excluding force.

Placed in the context of Athletic Club Bilbao it is appropriate to quote a recent club statement – transmitted on twitter – that “we put in value the bet of Athletic for a football with value, sustainable, responsible and local. Even more when it comes to women’s sport and football”.

Given that the nuances of this statement are possibly diluted in translation – at this point it should be mentioned that the Basque language, Euskera, is not only the oldest in Europe but also not the easiest to translate – the sheer joy of Bilbao on the day of a La Liga game is comparable to Cardiff on a Six Nations Day.

Everywhere supporters wear the club colours and every balcony sits draped with banners. It is a happy coincidence that San Mames occupies as central a position as the Millenium/Principality and it provides a similar focal point for emotion.

The ‘edge’ is present in many forms, rarely hostility thankfully, and its ‘nationalism’ pervades the air as an enveloper, an ‘including’ force.

Support Nation.Cymru’s work? We’re looking for just 600 people to donate £2 a month to sponsor investigative journalism in Wales. Donate now!

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.