‘It’s the end of the world’: Why we should remember the clearing of Epynt 80 years on

Angharad Tomos

It’s the detail that gets you – the old woman outside the house before they left, the army officer who could not pronounce Welsh place-names, the man whose home was blown up. They all add up to the memories of a community that was displaced.

Displaced communities are not new, just that this one happened in Wales, and it’s not Tryweryn. The sad story of Capel Celyn has won its place in the memory of the people, Epynt has not. That is why, 80 years after the Chwalfa (the Clearing), Wales should commemorate this atrocious chapter in its history.

The Army had its eye on Epynt during the First World War, when they first drew up the list of farm names. The mountain, whose name means ‘the way of horses,’ lies between Builth Wells and Llanwrtyd to the north and Sennybridge and Brecon to the south. As the brown Hillman Minx made its way up the lane in September 1939, the thing that drew attention was that it had a female driver. Out of the car came an army officer and he went into the classroom. As the teacher came from outside the area, she had no knowledge of the farms, so she asked the children to help.

Shouts of mirth broke out as the officer attempted to pronounce Ffos yr Hwyaid, Gilfach yr Haidd, Cefnbryn Isaf and Llwynteg Uchaf. But it was the officer who had the last laugh. By December, each of these fifty-two farms had received a notice. They were to vacate their homes by the last day of April, 1940. Epynt was to be turned into a Firing Range.

At 4.00am on Christmas Morning, 1939, the people of Epynt walked with their lanterns to Capel y Babell, some on horseback, as they had done for centuries, to the Plygain service. They sang the Plygain songs until the day dawned. Some must have wondered where they would be in twelve months time. It seemed incredible that they would not return. Babell was the centre of the mountain community. It was here they would come three times a day on Sundays. It was here that they baptised their babies, married, and buried their loved ones. It was here that they held the annual Eisteddfod, and the Gymanfa.

Things happened so quickly. They appealed to the Army, saying that the end of April was in the middle of the lambing season. How could they sell their animals and find somewhere to live in so short a time? They were granted a further month. There was no great protest, just disbelief.

Record

The Army seized 30,000 acres at Epynt, and forced 52 families – over 200 adults and children – to leave their homes. By the last day of June, a grey day, the last families were leaving. It happened at the same time as Cardiff and Swansea were mercilessly bombed. Of course, it was sad, but Britain was under siege. What choice was there?

They left the farms as they were, thinking that they would eventually return, when the hellish situation was over. One thinks in particular of Thomas Morgan who came up every day to Glandŵr to light a fire in the hearth. He didn’t want the house to fall into disrepair. The soldiers told him to stop, but he kept returning. One day, he approached the farmhouse, and it wasn’t there. The soldiers had blown it up.

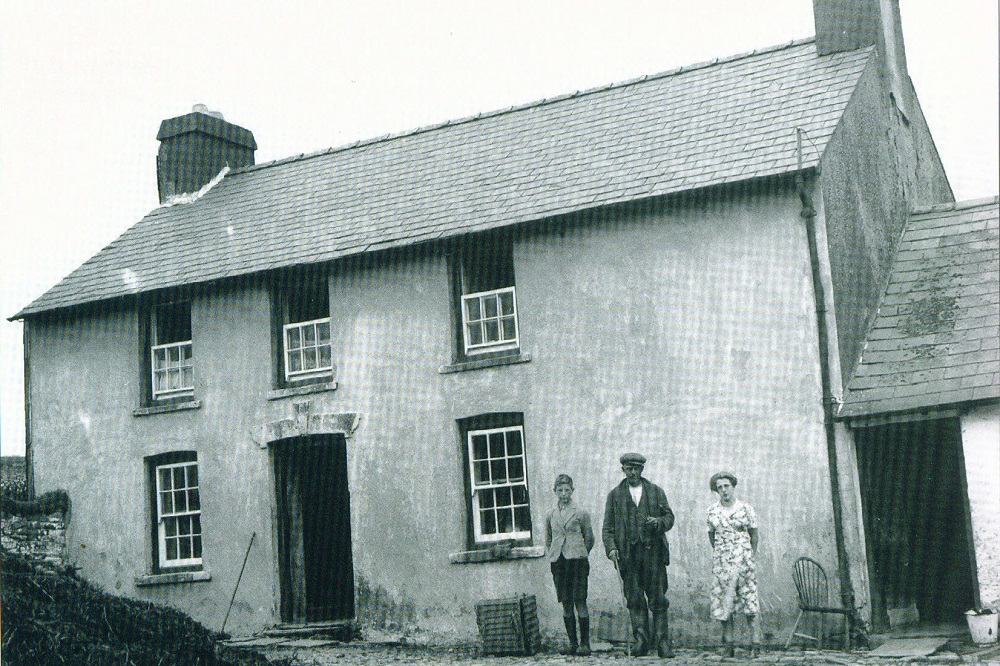

Slowly, it dawned on them the people of Epynt. They were never going to come back. Maybe some of them knew all along. One woman insisted on taking her front door with her. Iorwerth Peate, the curator of the Sain Fagan Folk Museum, decided to go up on the last day with his camera to record the occasion. Outside Waunlwyd there was a lorry at the back of the house busily being packed with furniture.

Peate went round to the front after receiving permission to photograph. It was there that he saw an eighty-two-year-old woman sitting in an armchair, her back turned to the house, and tears trickling down her cheeks. She had been born in that house, as her father and her grandfather had been. She sat there, motionless, and feeling he’d transgressed on a private sacrament, Peate turned away.

But she had noticed him, and without moving her head, she called him and asked where he was from. When he replied ‘Cardiff’ in Welsh, she softened, and the tears flew freely. “Fy machgen bach i” she said, “ewch yn ôl yno gynted ag y medrwch, mae’n ddiwedd byd yma”. (“Young boy, return there as soon as you can, it’s the end of the world here.”) And though Peate was aware that German bombs were falling on Cardiff at that time, he knew that she spoke the truth, and that it was the end of her world.

Harsh

Could the community have been saved? Given the political atmosphere in 1940, I doubt it. But contrary to Capel Celyn, it hasn’t been drowned. Maybe there is a hope of getting the land back.

I first visited Epynt in 1992. Cymdeithas y Cymod (Fellowship of Reconciliation) invited me there to talk at a rally, having had permission first from the Army. I had not heard the story of Epynt, and I felt guilty. What I had not prepared myself for was the FIBUA (Fighting in Built Up Areas). Having pulled down the chapel, the school and the farms, the Army has built a mock village there. There is even a mock cemetery with pretend gravestones which soldiers can hide behind. At the time, the streets had Serbo-Croat names, it being the time of the Bosnian war. It is not hallowed ground anymore. They are killing fields.

Glyn Powell’s family were amongst those that were turned out from Epynt, but Glyn returned. Not out of choice – he was doing his National Service. It was the 50s, the Korean war was being fought, and Glyn was taught to be a soldier on the land that his parents and grandparents had farmed. Now in his 90s, he recalls the harsh conditions, sleeping in the cowshed of Ffos yr Hwyaid on sheep droppings and being bothered by flies. His grief is that the heart of Brecon’s Welshness was ripped out.

Glyn and other children of Epynt are still campaigning. Epynt’s land has been destroyed by explosives and will never be farmed again. Since the 90s, the Army has taken more land around Epynt. It is there that soldiers of Afghanistan and Iraq were trained. It is a terrible legacy.

Lost

But if nothing else can come out of it, the story must live on. It has been passed from Glyn to his daughter Bethan, and she has passed it on to her children. A Facebook page Atgofion Epynt has been set up recently, and daily, the names of the lost farms are being shared on social media. When a family was in need of help in Epynt, the custom was to lay out a white sheet and the neighbours would call by. I think of the Facebook page as a modern version of the white sheet.

It is a cautionary tale, of how land can be exploited, of a community that was lost. It should be on the syllabus of every school, in Wales and beyond.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.