Lloyd George was a man of empire, and that empire was brutal

Adam Johannes

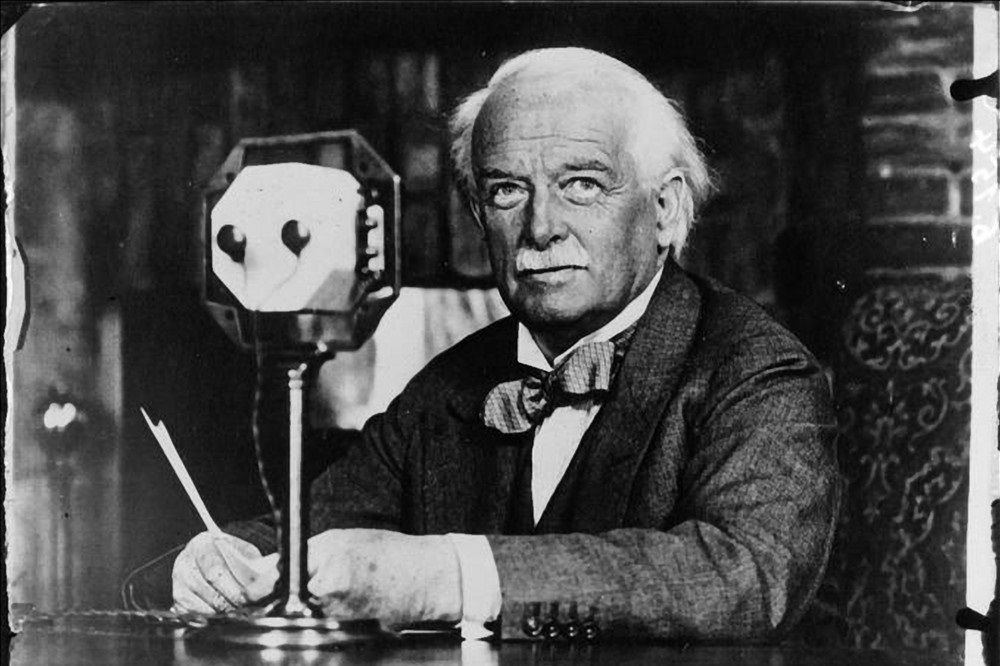

Lloyd George: a name heralded in history books as the architect of reforms—the old-age pension, unemployment and health insurance.

To many, these changes are his legacy, a portrait of a man who sought to ease the hardships of the working class, yet dig deeper, and the shine fades.

These reforms were concessions offered by the establishment out of fear of losing ground to the rise of trade unions and socialism.

But there’s an even darker story here, one that polite histories are reluctant to tell. Lloyd George’s legacy extends far beyond domestic reforms; as he climbed the political ladder to the summit of power, he entangled himself ever more deeply in the machinery of the British Empire, a machine powered by violence, exploitation, and racial domination.

Empire

The Empire was no gentle overseer; it was a merciless conqueror, built on the backs of colonised people across the globe. Lloyd George was no passive participant in this project, he served it, justified it, and grew powerful within it.

As Prime Minister, Lloyd George expanded the British Empire to its greatest ever extent, covering almost one-quarter of the surface of the world and subjugating almost one-fifth of the people of the world.

Lloyd George’s hands were not clean; they were stained with the blood of those whose lands, lives, and futures were devoured by the imperial appetite he so faithfully served.

Yet even today, mainstream narratives—histories, biographies, press accounts—routinely sanitise Lloyd George’s legacy, presenting him only as a reformer, the people’s champion. But this image is a mirage.

He was no saint, no champion. He was a man of empire, and that empire was brutal.

Lloyd George was a grim reaper, marching young men into the trenches of World War I in their hundreds of thousands, into a slaughter he and his ilk engineered for their profit and power.

He didn’t fight for the ‘war to end all wars’; he fought for a war to end all humanity, to devastate nations His true allegiance lay with the interests of a system that saw human lives as currency, to be spent and discarded.

And we’re supposed to honour this imperialist butcher?

Cutthroat

I will now outline some crimes of Lloyd George that recently led to pro-Palestine and anti-war campaigners to call for his statue in central Cardiff to be torn down; World War I

Since 1914, British troops have been in action somewhere around the world every single year.

What a horrifying legacy, and yet we see the brutality of World War I dressed up as heroism, sending young working class men into hellish trenches for empire marketed as something to glorify.

Lloyd George’s name belongs in the history books – but not as a hero, rather as the poster boy for a war machine that’s still roaring today.

Europe then was a powder keg of alliances, rivalries, and military arsenals, each country jostling for markets and dominance. Germany, far from alone in its ambitions, was one of five powers in a cutthroat scramble for wealth and colonies.

The resulting war would kill 16 million, each a casualty of the greed and schemes of these powerful rivals. And Lloyd George? He was the worst of them all, a man who played with the lives of millions like chips on a table.

The justification for war was German expansionism, but Britain already had the largest empire, its navy outmatching all. Germany was simply a late player in the game of imperialism where everyone was guilty.

Britain, with its colonial atrocities, pretended to defend “little Belgium” while smashing its own colonies.

World War I was never for the people. It was for power, and Lloyd George wore it like a crown.

Some sold the war as Britain’s righteous stand for Belgium’s sovereignty, a flimsy cover for a greedier motive. Plucky little Belgium – a country that had recently slaughtered millions in Congo for profit.

Britain, which savaged Ireland during the war, and ruled colonies around the globe, hardly was a defender of “democracy” or “independence.” Lloyd George’s war for “freedom” was hypocrisy at its finest.

35,000 Welsh Men

Thirty-five thousand Welsh men would never return from the Great War, with blood spilled in Mametz Wood and the mud of Passchendaele.

The toll was merciless: In Cardiff’s Grangetown alone, 500 men never came back, from Carmarthenshire 2,700 perished, 1,100 from Cardiganshire, 1,300 from Pembrokeshire, entire communities stripped of fathers, brothers, and sons, all for an empire that saw them as expendable in a war that served not their interests but those of the powerful.

Lloyd George, the prime minister, carried on in London as communities withered under grief, robbed of their sons.

In 1917, the Eisteddfod would crown a poet who would never rise to receive his honour. Hedd Wyn, fallen at Passchendaele, was to have claimed the chair, but his life had been sacrificed for Lloyd George’s war.

Lloyd George, himself a Welshman whose first language was Welsh, sat in the audience, aware of the cost but unmoved by it. The empty chair draped in black became a symbol not only of Hedd Wyn’s lost potential but of the imperial hunger of men like Lloyd George that had annihilated an entire generation, leaving only empty fields and traumatised families in its wake.

The working class men promised by Lloyd George they would return to ‘homes fit for heroes’, instead returned to hunger, the dole queue and the ‘means test’.

1916: Sykes-Picot Agreement

Sykes and Picot—a pair of empire men whose names still cast a long, dark shadow over the Middle East, a century after their ink dried on a secret deal.

They were British and French diplomats during World War I with polished shoes and polished lies, carving up the Ottoman Empire with a flick of the pen and no more regard for the people they’d condemn to a century of turmoil than they would for pawns in a game of chess.

They drew lines in the sand, boundaries with no roots in history or humanity, and the map of that betrayal endures today.

The British Empire under Lloyd George had dangled before the Arabs a promise of freedom, a single pan-Arab state stretching all the way from Aleppo to Aden. They encouraged the Arabs to revolt against the Ottoman Empire, but backroom deals were already in motion, sealing the fate of the region.

While Arabs fought and died, believing they were liberating a homeland, the ink was already drying on a different kind of future—one where their lands and their lives would be bartered, torn apart, and sold out to Western profit.

After the revolution took Russia out of the war, Leon Trotsky would publish the Tsar’s secret agreements, revealing to the world that the great powers had doubled crossed the Arabs. The Sykes-Picot agreement was a masterpiece of imperial control, a map with borders drawn not even with a whisper of local consent, but by great powers who cared little of the people they were dividing.

The new boundaries and borders were to serve the West, not those who lived within them.

The chaos we see now in the Middle East is no accident; it is the legacy of Lloyd George and Sykes-Picot. What some call ‘sectarian violence’ is a direct product of lines drawn in ink and blood by Britain, pitting Sunni against Shia, tribe against tribe, state against state—a region at war with itself for a hundred years and counting.

This turmoil has proven profitable for the oil giants, arms companies and Western powers alike.

For the people of the Middle East, this was a curse. For Western powers, it has been a blessing. The West has no interest in undoing this mess because it is no mess at all. It is their system, a design of control to keep the Middle East permanently fragmented, its wealth extracted, and its people forever betrayed.

1917: Balfour Declaration

In 1917, Lloyd George’s government promised the Zionist movement a Jewish Homeland in the Middle East while abandoning the Palestinians to a future of loss. The Balfour Declaration on the future of Palestine, signed and sealed in Britain, spoke of a home for one people on land belonging to another.

Edwin Montagu, the only Jewish member of Lloyd George’s Cabinet, would lead parliamentary opposition to the Balfour Declaration.

Ronald Storrs, the first British military governor of Jerusalem, would later state Britain’s hope for “a little loyal Jewish Ulster in a sea of potentially hostile Arabism,”. Britain wanted a reliable ally to help guard its control of the Suez Canal—the pathway to India—and the oil supply for Western interests.

Palestinians regard the document as the overture to the loss of their homeland thirty years later to make way for the modern state of Israel.

Dispossessing the Kurds & Massacres of civilians

Lloyd George’s policies helped make the Kurds the world’s largest stateless nation.

After World War I, the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres offered a fleeting hope for Kurdish autonomy, British officials under Lloyd George had encouraged Kurdish leaders to revolt with vague promises of independence, but when the borders of the Middle East were drawn, Lloyd George and his allies prioritised British and French interests, dividing Kurdish lands across Turkey, Iraq, Syria, and Iran without regard for the Kurdis.

Iraq, rich in oil, was brought under British control under a centralised regime, with no provision for Kurdish self-rule. This betrayal condemned Kurds to generations of marginalisation and violence across four states.

The Rowlatt Act passed by Lloyd George’s government made it legal for British forces to arrest and hold Indians without trial. On 13 April 1919, thousands of Indians gathered in an enclosed park in Amritsar, the Jallianwala Bagh, which had only one accessible exit.

Some gathered were protesting British rule, others celebrating a Sikh festival. Without warning, Colonel Dyer, had his men block the only exit and shoot into the crowd. Over 1,000 unarmed civilians would be shot dead in cold blood.

What happened in Amritsar was no rogue act, no “bad apple” amongst Britain’s officers in India, as key members of Lloyd George’s administration would portray it amid public outcry. It was Empire, pure and simple. Dyer pulled the trigger, but Lloyd George’s government handed him the gun.

When Dyer fired on that helpless crowd, he was only carrying out the spirit of British Empire policies. And then they blamed Dyer for doing what they’d empowered him to do. Lloyd George and his cronies knew that colonial rule was built on violence—it just so happened this time, the world caught a glimpse.

Massacres of unarmed civilians under Lloyd George would continue with Bloody Sunday on November 21, 1920, that saw the British Army once again open fire on an unarmed crowd, this time in Croke Park in Dublin, killing and injuring over 30 civilians.

Terror in Ireland

When Sinn Fein won a landslide in the 1918 Irish election, Lloyd George had a chance to honour Ireland’s democratic choice, and give Ireland the independence its people had overwhelmingly voted for. Instead Lloyd George saw Ireland as just another colony to manage, to be pacified by brutality and divided to keep it weak.

Faced with the Irish War of Independence, Lloyd George’s response was unleashing paramilitary “Black and Tans”, Auxiliaries, police and soldiers. Death squads would target Irish republicans and collective punishment would be imposed on entire towns.

The 1920 Burning of Cork would see 24-hours of terror. The burning out of the commercial centre would see hundreds of homes and businesses burned and looted making entire families homeless and leaving 2,000 men jobless.

Lloyd George’s government would release a statement that the Irish rebels had burned their own city to the ground, but as the foreign press descended to photograph and report on the destruction, it was clear to all that the British were responsible.

This was not the first reprisal attack; earlier that year, the Black and Tans rampaged through the small town of Balbriggan. Later that year, the siege of Tralee would see a curfew imposed, locals who appeared on the streets shot at, businesses forced to close, all food and drink blocked from entering the town, the town hall and shops burned down and civilians shot dead.

Throughout Britain’s terror campaign the line of Lloyd George’s government would be that British forces under terrible Irish provocation had ‘lost control of themselves’, that the reprisals were merely spontaneous outbursts of police pushed to breaking point by what Lloyd George called a ‘criminal conspiracy’ of Irish extremists.

Perpetrators would go unpunished, and in private, Lloyd George justified war crimes arguing reprisals had always been used in Ireland to ‘check crime ‘from time immemorial’.

Partition

Lloyd George’s partition of Ireland against the wishes of the majority of its people was the Empire’s final act of betrayal, a bitter legacy that left Ireland fractured. The British carved out a northern enclave, clinging to its industrial wealth.

What emerged was a state built on sectarian lines, a place where Catholics were relegated to second-class status, their rights shredded, their communities condemned to poverty and surveillance. This was the grotesque logic of Empire—divide and rule, pit neighbour against neighbour, stoke hatred as a tool of control.

Its First Prime Minister’s James Craig’s slogan of a “Protestant state for a Protestant people” was the British Empire’s dying sneer, a guarantee that Northern Ireland would remain a ghetto of Britain’s making, simmering with resentment and injustice.

Massacres from the Skies

Lloyd George is often praised for founding the Royal Air Force, but its true purpose was far grimmer. It was not built as a shield against invading armies but as a weapon to control the Empire from above—to bomb civilians into submission and keep colonial rule cheap.

During the Third Anglo-Afghan War in 1919, British forces bombed Afghan villages to silence demands for independence. This method of control would become Britain’s tool of choice across the Middle East.

Revolts from 1919 onwards swept the Arab world in response to the colonial powers’ betrayal, as Britain and France carved up the Middle East with a blatant disregard for promises of self-determination and in response, the British government, under Lloyd George, deployed its newest weapon. Iraq and Egypt were bombed, their people machine-gunned, their fields set ablaze.

This was no isolated repression; it was systematic, a coordinated effort to crush every cry for independence under waves of aerial assault.

In 1920, the Iraqi Revolution—a sweeping uprising against British occupation—was met with brute force. Lloyd George’s government authorised aerial bombardment, sanctioned by Winston Churchill, then Secretary of State for War, who suggested the use of poison gas against “uncivilised tribes.”

An RAF wing commander, J.A. Chamier, instructed pilots: “The attack with bombs and machine guns must be relentless and unremitting and carried on continuously by day and night, on houses, inhabitants, crops and cattle.”

A young Arthur “Bomber” Harris, later infamous for firebombing Dresden, reported with chilling detachment, “The Arab and Kurd now know what real bombing means, in casualties and damage: They know that within 45 minutes a full-sized village can be practically wiped out and a third of its inhabitants killed or injured.”

Lloyd George’s RAF applied these tactics against the 1919 Egyptian Revolution too. In Cairo, Sir Ronald Graham advised that news of bombed villages and collective punishments be censored “otherwise questions in Parliament are almost certain to arise.”

These massacres under Lloyd George’s watch epitomised the British Empire’s willingness to resort to terror to maintain power, reducing colonial subjects to targets, and suppressing freedom with ruthless efficiency.

First Casualty of War

The first casualty of war is always truth. In 1917, Lloyd George, ever the master of the art of deception, with chilling frankness, acknowledged to CP Scott, the editor of The Guardian, that the government and the press closely colluded to keep the horrors of the war hidden from the public. “If people really knew the truth, the war would be stopped tomorrow,” he bragged, “But of course they don’t know and can’t know.”

The British Empire’s war machine ran parallel to its attack on civil liberties. Lloyd George’s government clamped down on dissent, stifled democratic freedoms, and deployed a massive propaganda machine to shape the narrative.

Lloyd George would create the National War Aims Committee to ensure that propaganda flooded the public sphere, spinning a narrative of national pride while censoring the grim facts from the front.

The truth about the real cost of war—of the high casualty tolls, of the brutal realities of trench warfare, of poison gas and shell shock, of the thousands of young lives shattered for imperial power—was suppressed for as long as possible.

The War is Over

The end of the slaughter of World War I was not the result of Lloyd George’s largesse, but mass social unrest across Europe. In Russia, revolution brought down the Tsar and the Bolsheviks pulled Russia out of the war.

In Germany, a revolution in November 1918, ended the war on the Western Front. The sailors’ mutiny at Kiel, followed by a general strike and the collapse of the monarchy, brought down the Kaiser and forced the government to sign the armistice.

Lloyd George was a warmonger, a monster who sent young men to die, who trampled the rights of nations, who left behind a legacy of suffering that’s still felt today.

If we are to honour anyone, let it be those who fought against the Empire he stood for, the resistance fighters, the 20,000 conscientious objectors of World War I, the poet Siegfried Sassoon who hurled his medals into the River Mersey before making a speech denouncing the war, these are our true heroes.

Let Lloyd George be remembered as he deserves–as a man who fought not for humanity, but for Empire, for greed, for blood and glory. And let us not rest until we see a world free of his kind of imperial tyranny.

Lloyd George – we name you not as a hero, not as a liberator, but as a criminal of the highest order. And we, those who know and love justice, will make sure your name is never spoken in reverence again.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

I think that this is sufficiently biased as to be described as propaganda. Lloyd George was only one of a number of people administering the British Empire. It always surprises me that the Empire managed to last into the middle of the 20thC. With regard to Ireland the attempts to restore home rule were delayed by WW1 which largely drove the ensuing catastrophe. Partition turned out to be a mistake but was I believe an attempt in good faith to avoid an all out civil war. The First World War wasn’t started by Britain but was a result of a… Read more »

Thus spake the British Imperialist.

Well there’s certainly enough to think about there.

Presumably when Lloyd George ceased to be Prime minister the Empire was dismantled, wars were avoided, aggression came to an end and things became all well and good.

Seeing that the minus score is pilling up.

In addition to a comment that questioned the article’s implication that Lloyd George was and was alone the cause of all that bad stuff I might as well add a facetious comment.

Lloyd George knew my father.

Well done, Adam. A useful correction to the Lloyd George as ‘Welsh hero’ myth. As prime minister at the time of the imperial crimes you describe, he cannot avoid responsibility.

This article does not claim to be an unbiased assessment of Lloyd George’s life or political career. That would need also to consider his pre-war role around matters like his opposition to the Boer War, his support for Home Rule, his early steps towards a welfare state as Chancellor, or his battle with the House of Lords over death duties, as well as his corruption and many other issues. But it does remind its readers that he has much to answer for during his time as Prime Minister. A few comments here have raised questions about the First World War,… Read more »

As one of your respondents says above, Adam Johannes, we should be ‘proud of our great men’ and women. I believe that we are. But that is not to say that the loudest voices should be silencing discussion of who was great, or of what their greatness consisted. Thank you for contributing to that discussion.

Well said. The cult of the empire to bind Cymru to the english state was something to behold. And something happened to DLG to turn him into an arch imperialist.

A Llyn conspiracy; wasn’t El Lawrence born some ten miles down the road?

Today was not the best day, perhaps…

Great article. Much needed historical context added to the discussion. It is not, as some are claiming, to pin all the blame on one individual but rather to explain what exactly the system was that he presided over. To show how the decisions made in this crucial period of empire reverberate to this day.