The end of the age of innocence? Looking back at the Six Bells mining disaster

Today marks the 59th anniversary of the Six Bells mining disaster, near Abertillery.

Forty-five miners were killed at 10.45am that day – the worst post-war colliery disaster in the South Wales coalfield.

On the date of the explosion, 1,213 men were employed underground and 239 on the surface. A 24-hour, three-shift regime operated, apart from Sundays, producing 1,800 tons of saleable coal each week.

The disaster happened when an ignition of firedamp, a combustible gas associated with bituminous coal, caused coal-dust to be raised and ignited.

The Public Inquiry which later followed stated that “lethal concentrations of carbon monoxide gas were present which suggested the men lost consciousness rapidly and death occurred within minutes”.

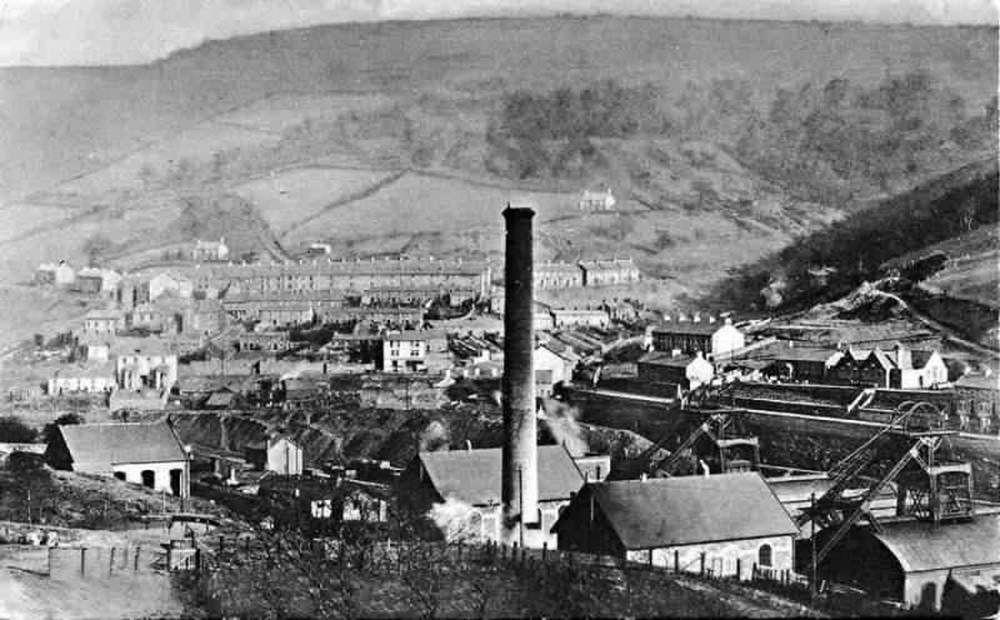

Six Bells village is on the southern end of Abertillery town and at the centre of an area that, to the date of this incident, contained a greater concentration of collieries than anywhere else in South Wales.

This photo, from an earlier decade, shows the Colliery contained on the floor of a deep valley. Many of its workforce lived within walking distance both then and in 1960.

The rail line provided the major means of coal and passenger transportation. Six Bells is some 15 miles north of Newport and virtually all avenues of communication were on this north/south axis.

Reporting

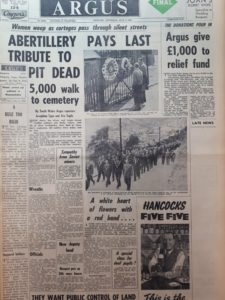

The first public indication of the disaster came on the same day, with an early edition of the ‘South Wales Argus’ (below).

From then on, the ‘Argus’ became the main means of public communication with daily front-page headline stories up to and beyond the coverage of funeral services, police and coroner reports, events in the Abertillery area and right through to the public inquiry hearings.

At the time, there were only two television channels and many households would have been without a set. The BBC’s ‘Welsh’ Home Service operated a limited broadcast time and telephones were a rarity in most homes.

Consequently, the crowds who gathered at the entrance gates to the colliery itself along with the workmen’s social club and the public house directly opposite became a major hub for information.

All 45 of the fatalities were named, along with their addresses, in the next day’s Argus.

Response

Within two days of the disaster, the Coroner had opened his inquiry and the funerals of 26 men took place on Saturday 2 July.

The official ‘Monmouth Constabulary Report on the Six Bells Colliery Explosion’ was completed on 13 July, less than three weeks after the disaster and is remarkable for its clarity, relevance and conclusion.

In brief; the description of a distinct chain-of-command, the identification of physical obstruction (sightseers, irresponsibly parked cars, etc.), identification of positive assistance fr

om other agencies (‘The liaison with Trade Union Headquarters was found to be of great advantage when dealing with the relatives of the deceased men’) and the need for regular statements on developments from a defined body – namely Police HQ – all stand out.

The whole report gives an indication of organisation and authority through a scene of potential chaos.

A Public Inquiry into the disaster then began at Newport Crown Court on September 19th and concluded on September 28th exactly three months from its date.

In the light of contemporary events, the Grenfell Tower disaster being particularly pertinent, this dateline is little short of astonishing. While accepting that the physical circumstances of the disaster were clearly defined and early identification of the deceased assisted greatly, 45 men were killed and each of them had different lives and relationships prior to it.

Inquiry

Inquiry

Presided over by T.A. Rogers, H.M. Chief Inspector of Mines and Quarries and with representation from (among others) the N.C.B. and N.U.M., the Inquiry’s brief summation was that the fatal explosion was caused by a spark being generated from a falling rock.

There was no evidence of negligence from the workforce contributing though incidents of malpractices involving irregular body searches and smuggled contraband did come to light.

The rigorous detail of the 1954 Act and the working hours restrictions go some way to denying any fault by worker or employer in causing the disaster, whether it be by lack of training, tiredness or clarity of operation.

Further, the fact emerges that the casualties were all men engaged on maintenance work. Had a more usual mining workforce been present in this particular part of the colliery, the death toll would probably have been much greater, by as many as three times over.

Innocence

In the closing months of this decade, there will doubtless be an upsurge of written and visual comment regarding ‘The Sixties’, 60 years on. That decade still dominates British culture and politics to an almost unhealthy degree with an almost Brexit like split between those who wish to move on from it or simply go back there.

In compiling this article I was myself drawn to the period before the dawning of the 60s, and the sense of lost innocence around its narrative. What the reports do not make clear is that the week of the disaster was one of unbroken sunny skies and unrequited peace and calm around a community that had ceased normal operation.

Perhaps the disaster marks a turning point in British society, the 5,000 black suits of the miners’ march to Brynithel cemetery about to be replaced by mini-skirts and electric guitars.

For an illustration of this, another historic page from the ‘South Wales Argus is reproduced, without further comment:

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.