The Long Read: When empires fail

Gareth Wyn Jones examines myths of Empire and present-day delusions of grandeur.

The famous Danish scientist, Niels Bohr, distinguished ‘two sorts of truth: trivialities where the opposites are obviously absurd and profound truths recognised by the fact the opposite is also a profound truth’. Bohr’s insight arose primarily from atomic physics and the anomalous behaviour of electrons. However the concept may have a wider resonance even in our modern society.

In 1882 Ernest Renan wrote: ‘Forgetting, I would even say historical error, is a crucial factor in the creation of a nation and for this reason the progress of historical studies often poses a threat to nationality. Historical inquiry, in effect, throws light on the violent acts that have taken place at the origin of every political formation’.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and its pseudo-historic rationalization has, on the other hand, highlighted an opposing truth. Such violence-based, possibly erroneous, founding myths also contain within them the seeds of catastrophe and the collapse of a nation quite as much as its ‘political formation’.

However the sting of ‘profound truth’ also lies nearer home.

Civilizing

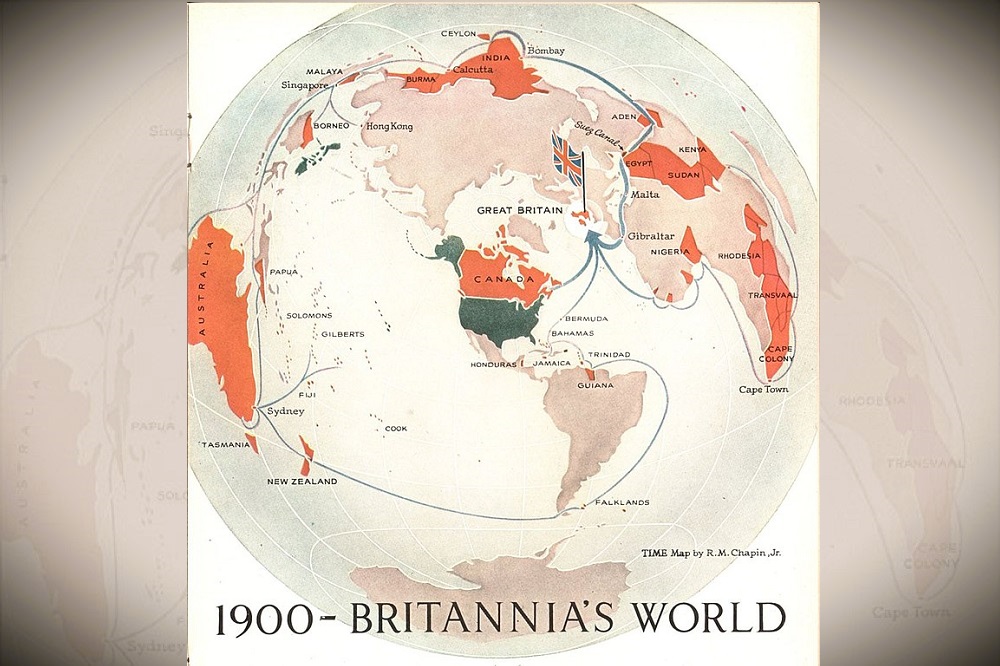

In my 50s school days the World Map was reassuringly red, supporting an unquestioning belief in Great Britain’s benign and civilizing mission. An imperial heritage our Headmaster explicitly espoused and to which his charges were expected to be enthusiastically committed.

Few now remember the short-lived ‘the new Elizabethan era’; a nation rejuvenated by a young Queen and the conquest of Everest. But the myths of Pax Britannica and a benign hegemony were and have remained omnipresent.

I do not recall our headmaster specifically mentioning the ‘white man’s burden’ but our imperial inheritance and Rudyard Kipling were a pervasive backdrop. Our privilege was to serve this tradition and re-establish bomb-scarred Liverpool as a great mercantile centre.

We, of course, heard of the Mau Mau, of troubles in Aden, in Malaya, in Cyprus and elsewhere but these were tangential to Britain’s great civilizing mission. Liverpool’s role in the slave trade and its prospering on the profits of exploitation did not surface. The great merchant palaces around Sefton and Prince’s Parks spoke of past glories not shame.

Horrifying

Caroline Elkin’s Legacy of Violence: A History of the British Empire is an unremitting and horrifying antidote to these rose-tinted memories. Building on her revelatory work on the violent suppression in the 1950’s of the Kikuyu rebellion against white land-grabbing colonists Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain’s Gulag in Kenya, she has extended her analysis to the wider empire, aided by newly uncovered files.

She details the responses of the imperial authorities to ‘incidents’ from the Indian Mutiny in 1857/8 and uprisings in Demerera (1823) and Morant Bay, Jamaica (1860s), through to the conflicts on the island of Ireland as late as the 1980s. Critically she also examines, and quotes extensively from, the main players in this tarnished history allowing their reasoning and self-justifications to become apparent.

She characterises the whole approach as ‘liberal imperialism’ underpinned by “legalised violence’ directed at producing a ‘moral effect’ on the childlike, unruly natives.

Critical to this ‘moral’ tale was a racial, often white-supremacist view in which the British male, as often from an Anglo-Scots or Anglo-Irish elite as English, regarded themselves as superior to the lesser breeds and with a manifest Christian destiny to guide, to rule and to chastise, sometimes brutally.

Charade

This rule could be relatively benign but, in the event of any opposition, calculated, sometimes extreme, violence, covered by a legal charade, was consistently applied. Given the perceived child-like and wayward character of the ‘natives’, be they white Irish or Boers, black Africans or Indians, Arabs or Jews, violence was not only justified but essential. Indeed the lesser breeds understood nothing else.

Paradoxically violence was perceived as part of the ‘essential moral force’ of civilization. In practice, the imperative was to instil in any opponent of the imperial regime or waverers, a greater terror of British authority than any terror or indeed loyalty which ‘rebels’ might engender.

The well-documented tactics included village burning and crop destruction, deliberate famine, murder squads, concentration camps, mass resettlement and deportation, rigidly controlled villages, rape, castration and torture. All supplemented by classical ‘divide and rule’ and calculated to imprint the psychological and physical dominance of the imperial power.

These, of course, have been and remain the classical tactics of all demagogues from Genghis Khan to today. Sadly they can be the resort of democratic states exemplified by Rumsfeld’s “shock and awe” and the destruction of Fallujah and Mosul.

Half-devils

Elkins traces the development of these tactics and their legal cover based on the presumption of a lower worth and minimal rights of the ‘half-devils, half children’, to use Kipling’s words, especially from around the 1850s and the rise of state racism after the first India ‘Civil’ War.

Especially revealing were the later machinations of successive British governments, Liberal, Tory and Labour alike, following both the World Wars and the rise of concepts of national self determination, universal human rights and international law, to ensure the retention of their coercive, colonial powers within a changing world despite their dwindling status and authority.

Domination

Repressive strategies and state-authorized terror date much further back than the Victorian era although, possibly, less conceptually formalized. Elkin evidences Callwell’s Small Wars; Their Principles and Practice (1896) as a crucial text in this formalization.

From the outset European expansionism was clothed in a culture of entitlement, of Christian self-justifying violence and deceit. Certainly the early settlement of New England and the expansion of European domination across the North America, as well as the displacement of the native peoples in what became the white Dominions, Canada, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand followed this pattern.

The conquered peoples were invariably seen as barely human and worthy of few, if any, rights compared with white European males, their families and descendants. However some legal cover for such activity was often sought.

Unarmed civilians

Few voiced the moral fervour of righteous violence more dramatically than Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer who ordered the machine gunning of unarmed civilians in Jallianwala Bagh, Amritsar on 13th April 1919 killing nearly 400, and leaving at least 1200 wounded.

In his own defence Dyer stated “I consider this (i.e. the killing of unarmed civilians) the least firing which would produce the necessary moral and widespread effect, it was my duty to produce — it was no longer a question of merely dispersing the crowd but one of producing a sufficient moral effect — not only on those who were present but more specially throughout the Punjab”.

In his stand he was fully supported by Sir Michael O’Dwyer, an Irish Catholic and Lieutenant Governor of the Punjab. This event caused a major uproar in the UK Parliament but many, especially in the Lords and the Army, defended Dyer. He was retired a colonel but died in 1926. O’Dwyer was assassinated in London in 1940 by an Indian nationalist.

The Amritsar massacre is but one of a sequence of massacres, killings and maimings documented by Elkins, which present an imperial inheritance either unknown, unrecognised or deliberately forgotten by the British public and most politicians.

Captive

Inevitably some of the colonized acquiesced and even welcomed the imperial power; illustrated in my personal experience in Lesotho. The population was spared some of the worst ravages of apartheid by becoming Basutoland, a British Crown Colony, but at the expense of losing about half of their best land. Undoubtedly also some colonial officers also gave devoted, if paternal, service to their ‘captive’ communities.

The overall admixture of care, service and dominance is superbly expressed by Kipling:

Take up the White Man’s burden –

Send forth the best ye breed-

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captive’s needs;

To wait in heavy harness,

On fluttering folk and wild –

Your new caught, sullen peoples,

Half-devil and half-child.

The fundamental contradiction reveal by Elkins is that liberal imperialism in seeking to export its values of the rule of law, private property, and individual freedom while continuing to enjoy the benefits of empire, was forced to resort to methods, although cloaked in legal fig leaves, which denied and undermined these basic values.

Worse, as opposition to imperial domination grew, the need for violent repression grew in parallel, be it in India, Kenya, Cyprus, Malaya or in Ireland. Pseudo-judicial violence became the norm. A downward spiral of bestiality then followed with both the colonised and the colonisers resorting more and more horrific and obscene methods.

The latter sought to cover their tracks by legal devices such as martial law and plenipotentiary powers. Few players were reprimanded; fewer still held to account in a court of law. In the eyes of the colonisers their brutality, euphemistically termed ‘frightfulness’ during the Mau Mau uprising, was morally justified. The violence of the colonized only reinforced their deemed, sub-human state of degradation.

Elkin’s analysis paints, in overwhelming detail, a picture of the British Empire which is rejected by its apologists including by most London-based newspapers and English populists including the Brexiteers and indeed most of the populace.

Zenith of empire

The popular public attitudes and my own youthful perceptions are engagingly and perceptively illustrated in Jan Morris’ Pax Britannica: The Climax of an Empire.

Interestingly it was Morris’ despatch, revealing the conquest of Everest by a New Zealander and Tibetan Sherpa, that arriving on Coronation Day, helped lauch the short-lived “new Elizabethan era’. Persuasively, using a series of colourful vignettes of lives of British colonizers and settlers across the globe as a device, Morris shows the seductive power, glamour, excitement and daring-do of the Empire at its zenith.

As one might expect, Morris is far too perceptive not to also, sotto voce, reveal the dark underbelly. For example, Lord Ellenborough, an early Governor-General of India before the ‘Mutiny’, is quoted as saying ‘India was won by the sword and must be kept by the sword’.

Conquest and domination without violence are barely imaginable. Unfortunately Morris refers to the colonisation of the ‘empty’ of lands of Australia, New Zealand and Canada. In practice, as in the Americas, the native populations were driven off their lands to make way for the ‘conquerors’ using tactic near identical to those described by Elkins.

To some this appeared the logical conclusion of competitive social Darwinism, for others, Christian destiny. Nevertheless in Pax Britannica the appeal of empire to both the ruling and working classes of Britain is vividly conveyed.

Seductive glamour

As might be expected some of the colonized also flourished such as many Indian Princes. They found ways to work within the system. Education in Eton and Oxbridge beckoned for a few and some thrived on the empire’s seductive glamour. Quislings are not, of course, confined to Norway, while many of the downtrodden remained inertly passive.

The expansion of the Empire, indeed all the European empires, coincided with and partly depended on the massive technological changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution: trains, roads, carbolic soap and medical care and latterly electricity etc.

So it is unsurprising that significant material progress did occur in many colonised counties. Such changes would and indeed did travel from north-western Europe without the trauma of conquest and colonisation e.g. in Japan.

Amitav Ghosh in his books, The Great Derangement and The Nutmeg’s Curse, argues cogently that colonization, in practice, restrained the economic growth of the colonised to benefit both the European capitalists and their working classes.

The colonies and later Dominions provided cheap raw materials and ‘Lebensraum’ for the rapid expanding populations of England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland as well as opportunities for excitement, advancement and wealth.

Democracy

During the Pax Britannica of the 19th century the British army fought dozens of wars from southern Africa and the North-West frontier, from China and to the Crimea. There was in reality no peace either in Europe or world-wide, only a dominant power, Britain, which was, to large extent, able to impose its authority by naval power, the telegraph and the mail.

The Empire spread the concepts of parliamentary democracy, the rule of law and Christian charity and expanded world trade but also depended the legalised perversion of these qualities and on formal religious and racist discrimination in order to sustain and enrich its elites.

Trade could be imposed such as, notoriously, in the Opium Wars in China. It instilled in the colonizers a deep feeling of white entitlement and superiority, which remains pervasive to this day.

However the emerging elites of the ex-colonies also learned to appreciated the power of legalised violence and suppression quite as much as any liberal, humanitarian agenda of free speech and democracy. Again this is illustrated daily in Sudan, Egypt, Uganda, Aden, Burma and Zimbabwe and increasingly India.

Entitlement

So the inheritance for both the colonizer and colonized is at best fraught. As Renan stated, historical studies pose a threat to our founding myths including those of the British, especially the English; a threat to an amalgam of entitlement and a belief in their own uniquely benign intent hiding a more rapacious and malign history.

This potent myth is then expressed in the treatment of the Windrush generation and the dominantly Afghani boat people seeking to cross the Channel, in our relationships with Europe and the rest of the world and, damningly, in the absence of any discourse on the reality of our imperial inheritance.

As Morris elaborates, the arguments about the relationship of these islands with the rest of the European continent as opposed to its sea-born Empire date back the Victorian era. Apparently Disraeli, partly by making Queen Victoria the Empress of India, won the argument with Lord Salisbury. Gladstone refused to attend Queen Victoria’s Jubilee. But at that time the imperialist vision prevailed although gradually it waned.

After World War II, Indian and Pakistani independence, the death of Churchill and, decisively, the Suez fiasco, it withered. Nevertheless the rose-tinted version of Empire and English exceptionalism has been an important inspiration to those wanting the UK to leave the European Union.

Indeed it is central to the desire for a new “Global Britain” and a new ‘Anglo-sphere’. The Cambridge historian and ardent Brexiteer, Robert Tombs, eloquently expressed his rejection of Europe in an recent article in the Daily Telegraph, concluding; ‘Our front door faces west, and our high road is the ocean’.

A crucial question arising from Renan’s insight and Bohr’s paradox is whether a founding myth based on a benign global civilizing mission but ignoring many unpalatable truths is constructive or destructive within a modern context. Is it the glue that unites the ‘nation’ and helps guide it forward? Or is it a conceit and deceit that undermines the ability of a nation to evolve in ways appropriate to an ever-changing world.

From any perspective, Putin’s vision, derived from a perverted version of Russia’s proud imperial and sacred heritage but, violently, denying the validity, identity and sovereignty of previously vassal states, seems entirely destructive. Destructive not only of Ukraine, Georgia, Moldova, Chechnya and possibly others but also of ‘mother’ Russia.

Unfortunately to some of the erstwhile colonised, western criticisms wreak of hypocrisy as they recall Fallujah, Hola camp and Amritsar and this tends to undermine coordinated global resistance to Russia’s aggression.

Global Britain

But what of post-imperial Britain? How valid is the vision espoused by the Brexiteers of a new Anglo-sphere, of a maritime, global Britain casting herself adrift from the continent of which geologically she is part in a period of increasing global unrest and emerging environmental crises.

If this vision is fraudulent and based on perverted version of the founding myth then the consequences of the hegemony of Boris Johnson, Nigel Farage and their political and intellectual colleagues will be discord and continuing decay. This prospect is all the more pressing as the benign imperial myth is increasingly an English perception.

The Empire held the nations of the British and Irish islands together; partly to exploit the spoils on offer but also because of the appeal of ‘national’ self-aggrandisement, entitlement and racial superiority. This cement is eroding rapidly. Neither Scotland or Northern Island voted to leave to EU. To the surprise of some ardent Brexiteers, the Irish Republic has consistently refused to be cowed by their agenda.

It is certain that the unique conditions pertaining in the early and mid 19th century will not return. Coal and steam are as no longer king. Science and technology are as much Chinese, Indian and Japanese as British, European and American. Environmental challenges ranging from global warming, plastic pollution and biodiversity loss and viral pandemics know no boundaries. Information flow, transport, industrial and food production chains and technologies are global.

Britain is no longer a world leader; except perhaps in the City of London’s ‘butlering’ of the oligarchs and the super-rich so allowing them to hide their wealth. There is no possibility of a new industrial revolution evolving at and being confined to a global point source. Any innovations within a very few years become globalized.

The myth of English exceptionalism, of an insular independence combined with a benign global reach, has become not only a mirage but a dangerous conceit; one that easily evolves into tendentious self-deceit, victimisation and false promises.

For some the insistence of the European Union on Britons now being “third parties” outside the Union and adhering to the letter of an International Treaty stems from a failure on their part to appreciate this uniqueness of this heritage.

It is a powerful myth dating to at least Tudor time and reinforced by empire:

this sceptered isle/This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars,?This other Eden, demi-paradise,/This fortress built by Nature for herself/Against infection and the hand of war,/This happy breed of men, this little world, /This precious stone set in the silver sea. [Richard II, Shakespeare]

For many this mythic vision was further strengthened by the World War II and ‘standing alone’. It is less frequently stressed that the war was only finally won with the joint sacrifices of American and Soviet (which included Russian) blood.

At Yalta and Tehran Churchill strove mightily to maintain the UK’s great power status. But within 15 years this myth, along with the sterling area, had collapsed. Tombs resurrects this conceit and rejects any, but the most trivial links to mainland Europe. He envisages Britain as new superpower presumably on par with the United States and China.

A devotion to false myths is obviously a disaster for Russia and its invasion of Ukraine. The English delusions may be less dramatic but could, if not challenged and reconsidered, be damning to us all and will create major dangers on these islands and abroad.

Gareth Wyn Jones is an Emeritus Professor at Bangor University.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

I wish to thank Gareth for this article. The UK is following the same fated path of the former Soviet Union. In both empires the belief of centralised exceptionalism led to those empires committing crimes against humanity. The warning is that Cymru-Wales has had a similar relationship with England as the Ukraine had with Russia throughout the last century or so. Could the same happen here? Before we can proceed: It would be better if Wales, Scotland, England and Ireland did become independent countries as recognised by United Nations. It would benefit all countries concerned and we will lead to… Read more »

I agree with you Ernie,but I doubt that the majority of Welsh people do.Most do not think of these things at all.Of the ones that do,since Macsen Wledig left have fantasized about ‘regaining’control of Ynys Prydain,it is not the same as the geographic island but a fantasy version of’England & Wales’ with us in charge.Some people this had been achived at Bosworth or when Lloyd George became PM.But neither Harri Tudur or DLG were fantasists.