A tale of tragedy and triumph: From Wales to Argentina via the Basque Country

Christopher Evans

Just over 85 years ago, Spain was torn apart by a brutal civil war that raged for over three years. In what was the bloodiest conflict since the end of the Great War, an estimated half a million people lost their lives.

The horrifying actions of General Franco, who had encouraged Hitler’s Condor Legion and Mussolini’s Italian Aviazione Legionaria to so brutally ‘terror-bomb’ the small Basque towns of Durango and Guernica, terrified families from the surrounding Basque cities and villages.

They knew that they would be next.

Following the atrocities of Durango on 31st March 1937, just under a month later, on 26th April 1937, the sleepy town of Guernica is said to have had over 31 tonnes of bombs ruthlessly dropped on it, with around 85% of buildings being completely destroyed. The ‘shock and awe’ tactics were designed to kill, destroy, and petrify civilians.

It is estimated that over 500 civilians (with some estimates in the thousands) were killed in the bombings.

An award-winning report in The Times by George Steer brought attention to the plight and horrors of the ancient and culturally significant Basque town. Steer wrote: ‘At 2am today when I visited the town the whole of it was a horrible sight, flaming from end to end. The reflection of the flames could be seen in the cloud of smoke above the mountains from 10 miles away. Throughout the night houses were falling until the streets became long heaps of red impenetrable debris.’

It was Steer’s reporting that further influenced the people of Britain, and Welsh miners in particular, in the fight against fascism.

In a show of Welsh internationalism, nearly-200 Welsh volunteers went to Spain to fight for the anti-fascist International Brigades. 35 would never return.

The terrified people of the Basque Country – Euskadi – were well aware that Franco’s barbarity would continue indefinitely.

The British government had shamefully declared a neutral stance on the war in Spain, but finally agreed to accept refugees (though with no financial support) following a desperate plea by the Basque Lehendakari (President) José Antonio Aguirre, a former footballer with Basque giants Athletic Club Bilbao.

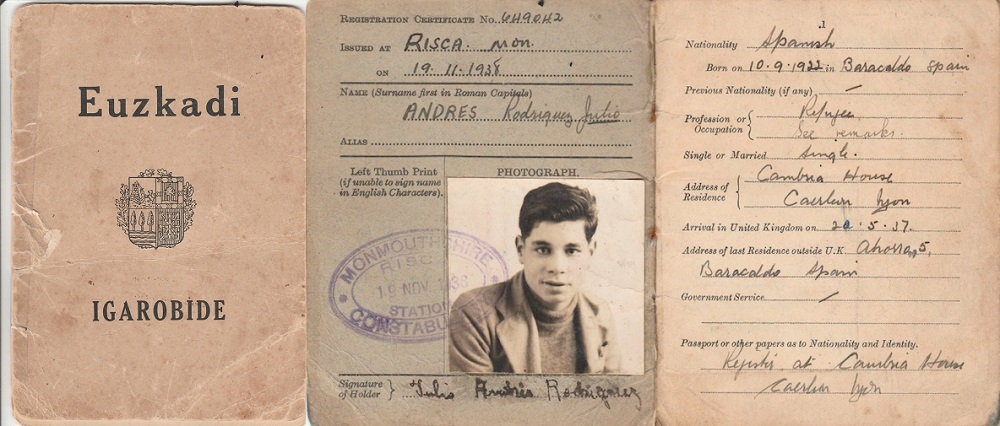

On 23rd May 1937, almost 4000 children arrived in Southampton aboard the SS Habana following a perilous crossing from Bilbao. 56 of these young Basque children (with two interpreters and three teachers) would be housed in Caerleon.

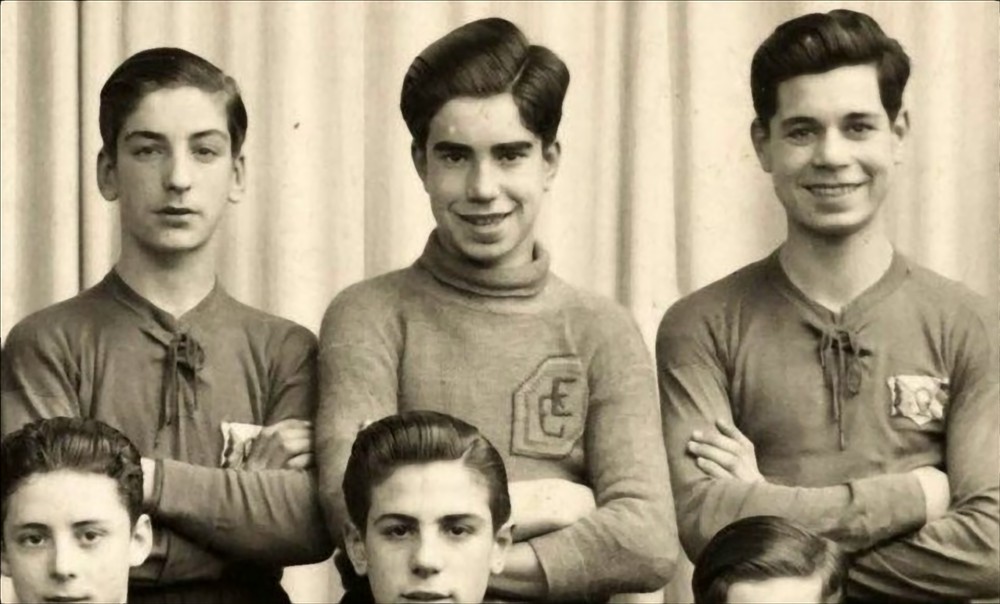

Basque Boys AFC of Caerleon

The incredible story of Basque Boys AFC of Caerleon has been told on Nation.Cymru, most recently through the discovery of more information of the incredible football career of their talented goalkeeper Enrique Garatea. The creation of the team was a form of escapism for the boys. It allowed them to bond and to create a purposeful and hopeful atmosphere at their lodgings at Cambria House in the centre of the village. It was here that the children were cared for so wonderfully by the house warden Maria Fernández.

Julio Andrés had arrived in Caerleon along with his brother Alberto. An accomplished young footballer, he played a huge part in the success of Basque Boys AFC. He was also a gifted writer and would write the match reports following the team’s escapades around south Wales.

Julio was amusingly vexed by a misprint in the programme of the boys’ most famous match against Cardiff’s reigning league and Seagre Cup winners Moorland Road School. The match, that was played in front of thousands of spectators at Cardiff City’s Ninian Park on Wednesday 10th May 1939, was won 2-0 by the talented Basques. However, the programme erroneously had Julio down as a substitute, much to the chagrin of the defender.

A three-day event took place in Caerleon in July commemorating the 85th anniversary of

the arrival of the Basque children refugees in Wales. Following the event, organised by the Basque Children of ’37 Association, the family of Julio got in touch wanting to know more about their ancestry.

Inspiration

The story of Julio and the Andrés family is one of great tragedy, but also inspiration.

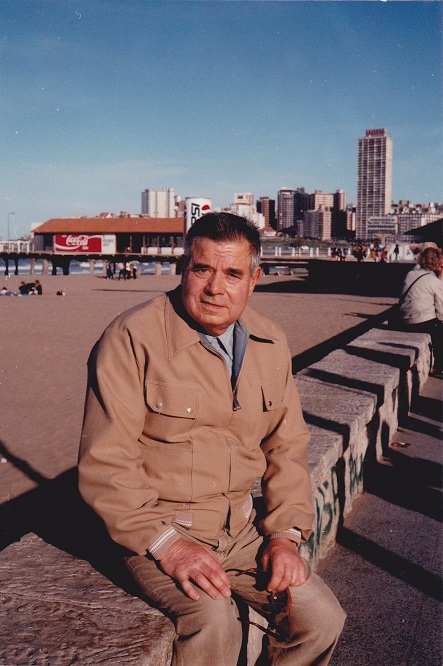

Gabriela Karina Andrés, who lives in the coastal city of Mar del Plata in the Buenos Aires province of Argentina, knew that her grandfather had been in Caerleon and that his identification number was 3856 (all the children were given a hexagon with a unique number upon their arrival in Britain), but was keen to find out more. When she found out about the footballing success of her grandfather’s team, she contacted her father, Jaime Luis Andrés, Julio’s son, who now lives in Tenerife. He was overjoyed to learn more about his father’s time in Wales.

However, the story of Andrés family is one of sadness and desolation. It resonates today, particularly with the on-going war in Ukraine.

Speaking from his home in the Canary Islands, Jaime’s story is sobering. ‘My father was sent to Great Britain with his brother Alberto at the beginning of the Civil War following the bombing of Guernica. My grandparents thought that after the war they would return, but it turned out that when Franco’s troops entered Bilbao, they captured all those who did not belong to the regime. This included my grandfather (Julio’s father), who was arrested because he was a trade unionist and had a son in the army. He was imprisoned in Galicia. It was there that he was shot.’

It was not just Julio’s father who would perish at the hands of Franco’s fascists. Sadly, his brother Luciano would also tragically lose his life.

‘Luciano (Julio and Alberto’s older brother) joined the Republican Army, where he lost his life in combat. Their mother (my grandmother) also lost two fingers on her right hand in a bombing raid.’

This corroborates with the work of Cyril Cule, the director of Cambria House, who wrote detailed descriptions of the personalities of the children who arrived in Caerleon.

Harrowing

In his unpublished manuscript ‘The Spanish Civil War: A Personal Viewpoint’, Cule writes about Julio’s family in his description of his brother Alberto. It is a bleak and harrowing read:

“Alberto, 12 years of age, is one of the nicest children at Cambria House. Slightly built, he has a calm, gentle temperament, and works diligently at his lessons. His mother was injured by an air-raid but is now at Barcelona. Alberto’s father has been held prisoner by the rebels for over a year. It is understood that he was thrown into prison because he was a member of a Trade Union.

“Some months ago, Alberto’s elder brother learnt that his father had been condemned to death, and nothing has been heard from him or his father since. This news has been kept from Alberto.”

With her husband and eldest son murdered, Julio’s mother fled the besieged Basque Country. “What was left of the family went to France. From there they eventually emigrated to Argentina, where they settled in Buenos Aires. At that time Argentina was a very prosperous and rich country.”

The Andrés family did not move to Argentina impoverished. Fortunately, Julio’s father Manuel and uncle had been cattle ranchers, moving cattle between Spain and France. They had amassed a small fortune and had decided to move to Argentina in the hope of a brighter future for their families.

After deciding to settle permanently in South America, his uncle sold his shares in the business. Julio’s father had returned to Spain with the plan of selling his business and returning to Argentina. In a turn of misfortune, the Spanish flu broke out, meaning that nobody was allowed to leave or enter the country. Julio’s father settled in Barakaldo near Bilbao, where Julio and his siblings Brigi, Alberto and Luciano were born. It was a mortiferous twist of fate that meant Manuel and Luciano would prematurely and brutally lose their lives.

Cambria house

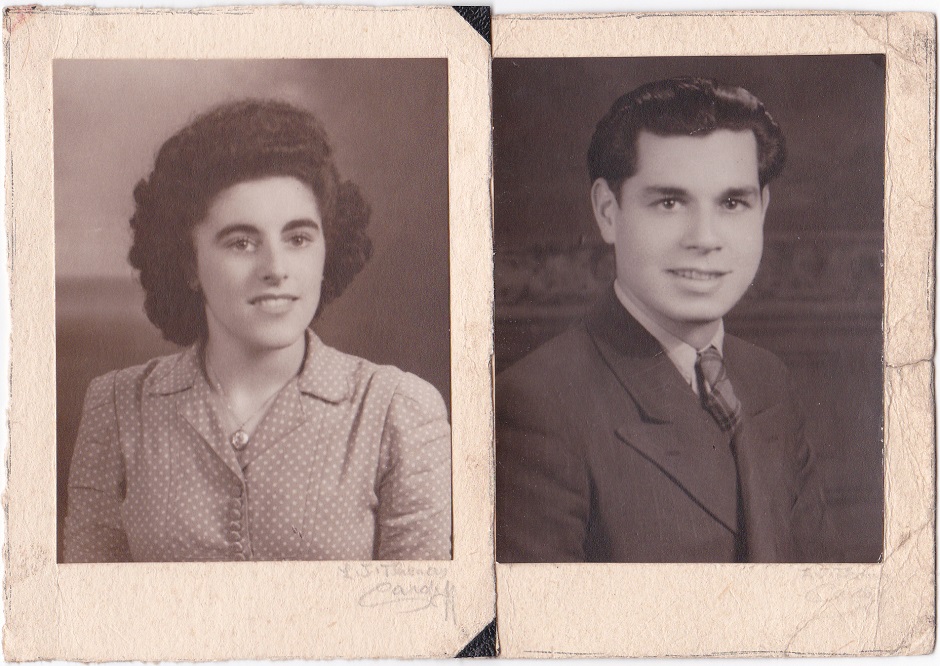

After the Civil War ended in 1939, World War Two began. Fascism was in a worrying ascendancy in Europe. It meant Julio and Alberto would not be returning to the Basque Country imminently. Julio’s ties with Wales would last a lifetime – he would fall in love with the niece of the aforementioned warden of Cambria House, Maria Fernández, herself the daughter of an ironworker from Bilbao who had moved to Dowlais for work purposes.

“My father and uncle stayed in Wales for another 10 years,” says Julio’s son Jaime. “In the Fernández house he met my mother Josefina, a niece of Mrs Fernandez. Her older brother Manolo had a small plastering business, so he worked with him.”

Speaking of his family’s emigration to Argentina, Jaime says “My aunt Brigi (Julio’s sister) married and had a daughter (Dolores). The three of them, along with Julio’s mother (my grandmother) sold what they had and arrived in Buenos Aires with my uncle and settled.

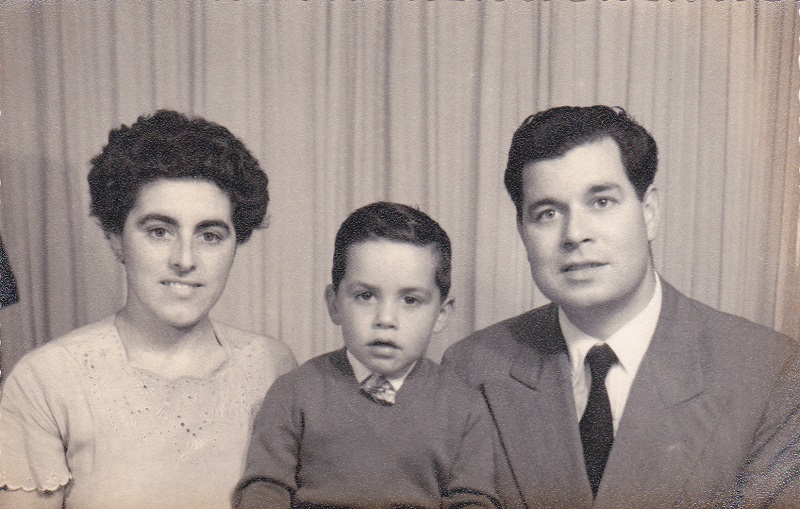

Julio (along with Alberto) would eventually join his mother, uncle and aunty in Buenos Aires in 1947, closely followed by his future wife Josefina, who arrived in 1949. ‘I was born two years later in 1951, and we moved to Mar del Plata in 1957. That is where my daughter Gabriela still lives, but she is hoping to move to Spain soon.”

Using the manual skills that he had developed in Wales, Julio worked in construction until his retirement.

The Basque boy’s love of football never wavered. He was a fan of Club Atlético San Lorenzo de Almagro (based in the Boedo district of Buenos Aires), and always passionately followed his home team, the unique Basque team Athletic Club Bilbao.

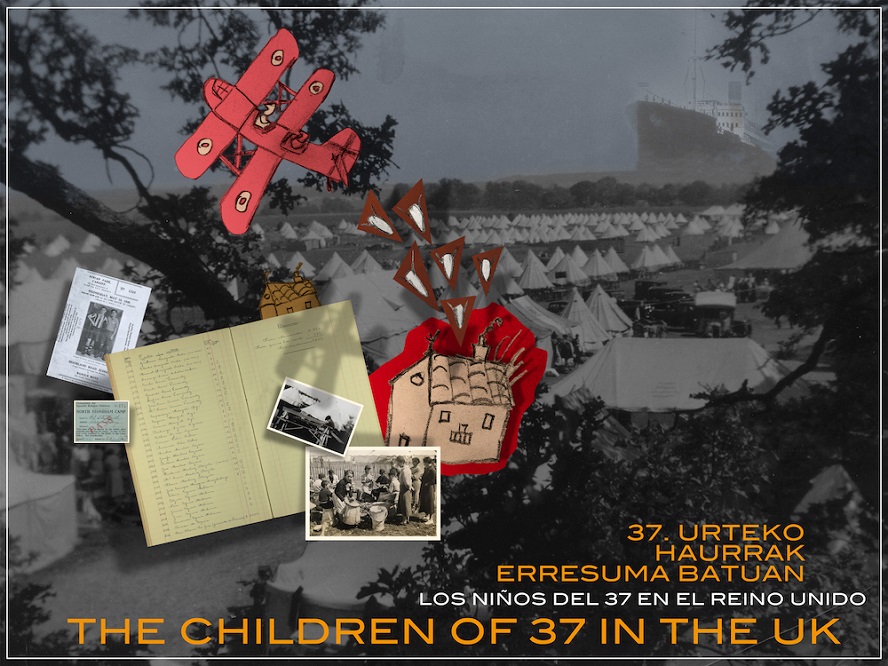

Little did the boy from Bilbao know that he and his teammates would one day be on display at his beloved Athletic’s iconic San Mamés stadium. The boys’ heroics are chronicled at the club’s museum as part of the ‘The children of ’37 in the United Kingdom’ exhibition that focuses on the children refugees who fled to the UK during the Spanish Civil War.

The story of Basque Boys AFC is extraordinary. It is the true story of refugees, young children, a team, ripped from their homeland, who overcame tragedy and the horrors of war to produce an inspiring tale of togetherness, hope, empathy, compassion and aspiration.

The tragic story of the Andrés family is a reminder of the colossus and indescribable pain and suffering caused by zealotry, greed and war.

Julio Andrés died on the 16th November 2002 at the age of 80.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.