Great expectations: The making of a Welsh rugby maverick

Luke Upton

What makes a Welsh rugby maverick?

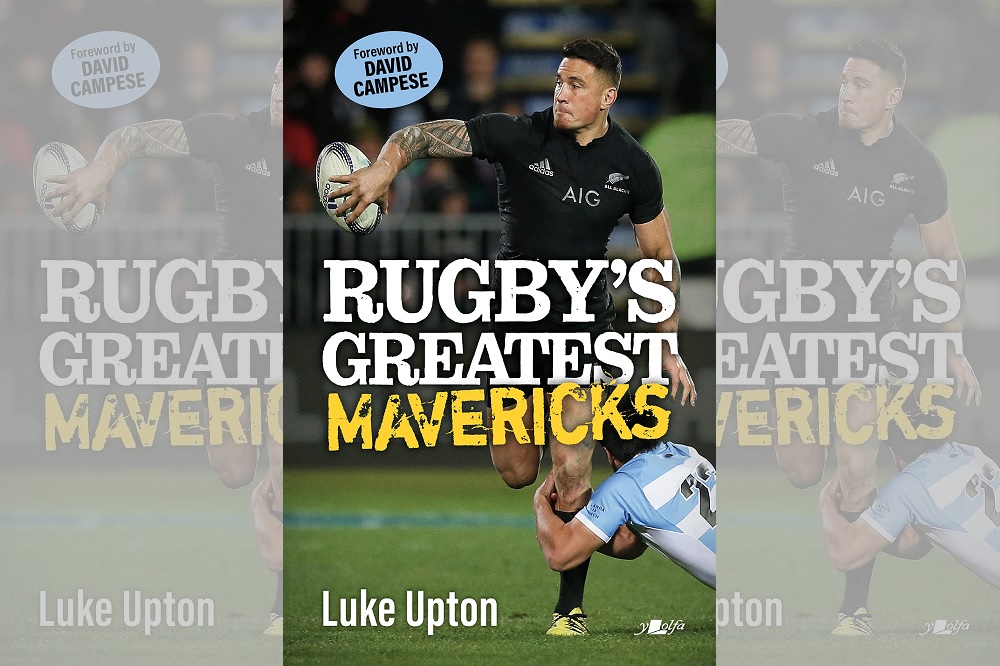

As I was finishing setting up for my book launch, a customer in the book shop wandered over to the table where I was awaiting a modest deluge of friends and family to arrive. I gave him my best salesman’s smile and we began a little chat about my new book, Rugby’s Greatest Mavericks (Y Lolfa).

He picked up a copy, scanned the text, then looked back up and said, Shane Williams must be in here, right? I laughed a little, and said, no he’s not.

I told him a few of the names that were featured, some very well known, others a little more unusual, a couple only familiar to a few. Among the full twenty included there are supporters of great moral causes, artists, crusaders, polymaths, pioneers and outcasts.

Several are heroes, perhaps a few are villains.

But Shane Williams is not one.

My new friend, snorted a little bit, put the book down and headed out the door of the Mumbles bookstore I’d been allowed to take over for one October hour.

Shane Williams was a wonderful, effervescent match winner who has given me, and most of you reading this, many special memories. But a maverick he is not.

I was fortunate that my publisher gave me freedom to use my own definition of what makes a maverick, and across my selection, the thread that runs through them all is an independence of spirit, a desire to do things their own way, a belief in their own path – which, whilst not always proved correct, is normally entertaining, typically memorable, occasionally disastrous, but always true to them.

Three Wales players made the book, yes, it could have been more, a book of Welsh Rugby Mavericks would be a lively read.

But in the end, I choose a trio that were all mavericks in their own different way, fantastic players, with lively careers and off the field stories and whose time in the game had thrown a spotlight on a particular moment in Welsh rugby history.

A complex man

Ray Gravell was in some ways an archetype, the big strong boy from Carmarthenshire, with a huge personality who was a part of a host of golden moments in the red of Llanelli RFC, Wales and the Lions, who became an even bigger figure as a broadcaster, actor and Grand Sword Bearer at the National Eisteddfod.

Gone too soon at just 56, he packed many lifetimes’ worth of achievements and memories into a life well lived. But the more I researched him, the more I saw a deeply complex man.

A keen rugby player from a young age, his warm Welsh village life came to an abrupt halt with the suicide of his father when Ray was just 14. And it would be the young Ray who found the body.

Despite all the trophies and caps he won, Gravell often felt a sense of nagging doubt about his own abilities. Moments before taking the field for big games, he would ask his teammates who the best centre in Wales was – just needing that little confidence boost from his own side before going out and smashing into his opponents.

I spoke to Steve Fenwick, a dear friend of Gravell’s and his centre partner with Wales for many years and asked about this aspect of his personality.

“He was the nicest guy you could ever ask to meet, but he was such a worrier about everything. People used to try and wind him up, particularly the boys from Bridgend and Cardiff. Someone would say just before kick-off, ‘Grav, you’ve lost weight – everything OK?’ and he’d spend the next 20 minutes asking Phil Bennett how he thought he looked.”

He shone for whoever he played, part of the famous Llanelli team that beat New Zealand 9-3 on Halloween 1972 and would tour South Africa with the Lions in 1980. A lively member of any touring party, Fenwick recalled to me another memory, from a Wales trip to Australia.

“We were in Sydney, running out on the pitch, when a bloke in the stand shouted at Grav, ‘Go home, you Pommy bastard.’ Grav stopped in his tracks and ran right over to him. The Aussie looked terrified as he got up in his face, then he said, ‘Call me a Welsh bastard, but never a Pommy bastard.’ The fella said shakily, ‘Sorry mate, I didn’t know the difference.’ Grav ran back onto the pitch, and we were all cracking up!”

Even today, 15 years after his passing, he is still very much in the public consciousness and in telling family and friends I was writing a chapter upon him, I was regaled with their own personal stories about the man.

Through the course of his career, he developed a strong, but never exclusionary stripe of nationalism, and as a friend of Dafydd Iwan, I think he would have loved the Welsh adventure in Qatar and the popularisation of Yma O Hyd. I wish I’d been able to interview him.

Making headlines

As Gravell was finishing up for Llanelli, a maverick of a different variety, Dai Bishop was making all sorts of headlines for Pontypool, but only once for Wales.

His talent was matched only by his self-belief and the scorn with which some of the Welsh rugby administration regarded him.

The late John Billot of the Western Mail called him “the best scrum half in Welsh rugby since the Second World War”.

Ex-Neath rugby supremo Brian Thomas called him the finest player in the northern hemisphere. Former England scrum half Richard Hill said he was, for a period in the 1980s, not just the best in the British Isles, but in the whole world.

First class

But this only tells a fraction of his story. A talented all-round sportsman, as a youth he had boxed for the Welsh amateur team and played baseball for Wales.

Several times he’d been in trouble with the law. He’d rescued a woman and a baby from a swollen River Taff. And this all before his rugby career properly started.

As a scrum-half, he made his first-class début for Ebbw Vale where he was outstanding. He then joined Pontypool in 1981, but not long after broke his neck. Despite being told he would never play again, he was back playing for Pontypool within a year.

He only gained one cap for Wales – against Australia during the 1984 Australia rugby union tour of Britain and Ireland which Wales lost 28–9. Despite the loss Bishop was the only player to score a try against them.

Bishop had played understudy to fellow scrum-half Terry Holmes, and when Holmes switched codes to rugby league in 1985, many expected Bishop to finally be given his chance to play for Wales permanently. However, during a match versus Newbridge, Chris Jarman received a broken jaw in an off-the ball incident.

Jarman brought a private prosecution resulting in Bishop being given a suspended jail sentence and an eleven-month ban by the WRU. The Welsh selectors instead picked Robert Jones of Swansea RFC.

Bishop however gained his revenge in 1987-88 when Pontypool defeated Swansea at Pontypool Park in the cup, the highlight of the game being Bishop’s penalty in the mud to seal the win, following which Bishop wiggled his rear end to the stand—where the Welsh selectors were sitting.

Unpredictability

Despite repeatedly putting in outstanding performances for Pontypool, Bishop was never picked for Wales again, though his case was not helped by several of his antics off the field.

The 1987-1988 season was the most successful in the club’s history when they lost only two games all season and Bishop formed a potent partnership with Mark Ring.

Superb for the all-conquering Pontypool, his omission from the 1987 World Cup squad, saw him pack in Union for League where he joined that golden crop of Welsh exiles thriving in the 13-man game in the last few years of amateurism.

Finally in 1988 he signed for Hull Kingston Rovers, and subsequently played for Salford and London Crusaders. He was then part of the Wales rugby league team that won a European Nations Cup and reached the 1995 Rugby League World Cup’s semi-finals.

For Dai Bishop, triumph and disaster were never far away. You can never accuse Bishop’s life of being straightforward. It’s probably fair to say that the only predictable thing about him was his unpredictability.

Whilst Bishop was able to earn a living as a professional rugby player by switching codes our third maverick, Non Evans, had to balance extraordinary performances on the pitch, with a full time job. And that only tells a small part of her story.

Gladiator

At 18, she’d already represented Wales in Judo, had begun talking rugby seriously and was studying when she started powerlifting, in which she would later represent Wales at the Commonwealth Games.

Wrestling would come later too, and she would wear the Wales vest in this too. She also made an appearance on Saturday teatime favourite, Gladiators.

She excelled at rugby, making her international debut at 22 against Scotland, and quickly made the Welsh full back jersey her own, winning 87 caps and scoring a remarkable 64 tries between 1996 and 2010.

The era in which she played was often a difficult one for the Welsh team, with the women’s game still in its infancy.

Evans recalls how it was in these early years.

“I remember reading the small newspaper match report of my debut match versus Scotland, and the reporter likened our standard to that of an U13 boy’s game. The media coverage was very limited. Normally our coaches were just using us as a stepping-stone to jobs in the men’s game, so didn’t care too much and moved on pretty quickly. Everything was a battle before we even got on to the pitch.”

But despite these challenges, when I asked her if things had been different, and she’d like to have been able to focus just on rugby and be paid for it.

“To be honest, no. I wouldn’t have wanted to miss the opportunity to do different sports. I sometimes joke that if I was a man, I’d be a millionaire. But despite all the juggling and organisation needed, I always enjoyed it, have so many memories and wouldn’t have had it any other way.”

So, there we have a whistlestop tour of my three Welsh mavericks, the big-hearted Scarlets legend with deeper layers than the booming laugh and easy smile might display, the talented spiky Cardiff boy whose face didn’t fit with the WRU and turned his back on the Union game, and the world class pioneer who juggled emails and spreadsheets with on the pitch excellence and off the pitch ignorance and neglect.

Gravell, Bishop and Evans were all maverick in different ways. But if they were all the same that wouldn’t be very maverick, would it?

Rugby’s Greatest Mavericks by Luke Upton is published by Y Lolfa, with a foreword by David Campese. It is now available from all good bookshops and online,

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.