The rugby life of dual-code star John Bevan

Simon Thomas

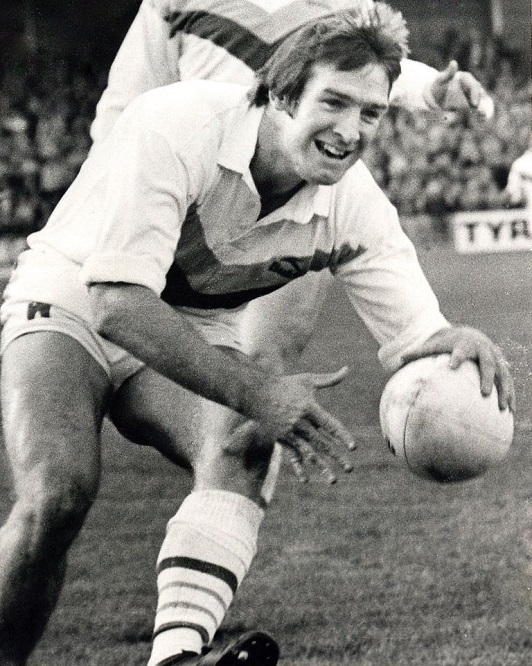

He was a Grand Slam winner and a triumphant Lion by the age of 20, he played in arguably the greatest game of all time at 22 and he was a Great Britain Rugby League international at 23.

It’s fair to say John Bevan achieved a fair amount before he was even out of his early twenties!

But that was far from the end of it. He was to spend 13 highly successful seasons in league with Warrington before returning to the 15-man game as the WRU’s director of coaching, also working with the national team.

Then there’s been the little matter of close on 50 years as a teacher, a role he still fulfills today at the age of 72 at Monmouth School, where he continues to coach rugby.

It has been some sporting life for the former winger – in both codes of the oval ball game.

Born in Tylorstown, in the Rhondda, Bevan attended Ferndale Grammar and his ability soon became apparent as he was capped by Wales at Schools level – but in the back row rather than the backs.

“I was the greediest No 8 going!” he admits.

“Nobody else had the ball when I picked up and they never caught me. So I was made for the wing.”

Having transferred out wide, Bevan – who worked in the mines every summer as a teenager – made his debut for Cardiff RFC aged just 18 in the autumn of 1969.

He soon caught the eye with his bulldozing power. Never have the initials JCB been more appropriate!

After just 15 games for the club, in which he scored 16 tries, he was called up to make his Wales debut against England in January 1971, marking the occasion with another touchdown.

He was to start every game during that season’s memorable Grand Slam. Such was the impact he made, with his strength and speed, that he was selected for the Lions tour of New Zealand in the summer.

It was to be some trip for a young man who was still a student at Cardiff College of Education, where he was studying PE and RE.

He was on the left wing for the first Test victory over the All Blacks in Dunedin, while he was a predatory presence throughout the 26-match adventure which took in a couple of games in Australia.

In all, he scored 18 tries, with the 17 he posted in New Zealand equalling the record of Irish great Tony O’Reilly from the 1959 trip. He claimed four against both Wellington and Manawatu, plus a hat-trick versus Waikato. He was virtually unstoppable.

Life-changing

Looking back now, he views the tour as a life-changing experience.

“I had never been anywhere properly before that. I had only been on a plane once, going out to France,” he recalls.

“I had never really been away from home, especially with complete strangers. I was a raw lad for three and a half months on that tour.

“My dad had to take out a second mortgage to get me spending money.

“I didn’t know what to expect. I was young and inexperienced and naive in many ways, but you have got to get on.

“You get to know people and you look after each other’s backs. That’s what it’s about.”

As for the rugby, he thrived amid the expansive approach adopted by coach Carwyn James, who masterminded what remains the Lions’ only series victory in New Zealand.

“For three and a half months, Carwyn said ‘Go out and move the ball’”

Following his return home, Bevan remained a fixture in the Wales team through 1972, again starting every Five Nations game, and scoring a try against New Zealand in the narrow 19-16 defeat at the end of the year.

A month later, he was to find himself facing the All Blacks again – albeit in very unexpected fashion.

He hadn’t been selected by the Barbarians for their showpiece fixture against the tourists at Cardiff Arms Park, but then fate took a hand with Gerald Davies having to withdraw from the game.

“Gareth Edwards rang me on the Friday night and said ‘Bev, do you fancy playing tomorrow?’,” he recalls.

“I said ‘Aye, ok’. It wasn’t a bad day in the end!”

Not bad at all, as it happens. It remains pretty much the most celebrated and replayed match in rugby history and Bevan certainly played his part, scoring one of the BaaBaas’ four tries in a famous 23-11 win.

Some 50 years on, it stands out in his mind as a game like no other.

“Normally on the wing, you don’t do much, you are called into action every now and then, but within five minutes of that game I was absolutely shattered with all the running around,” he says.

“The ball was in play so long. Normally where you expect somebody to kick the ball into touch, all of a sudden people start dancing in their 22 and counter-attacking.”

That adventurous attitude was perfectly illustrated just minutes into the game with what is dubbed the greatest try of all time, scored by Gareth Edwards. Few people had a better view of it than Bevan as it happened just alongside him down his left wing.

“I obviously took all the All Blacks out of contention because they were looking at me!” he quips.

“When my opposite number Bryan Williams kicked the ball downfield, I was just jogging back thinking somebody will kick it out to touch.

“But then when I saw Benny (Phil Bennett) dancing, I thought I better get back there. There were a couple of passes out of tackles and it just kept going. Usually the forwards would have just taken it in and set up the ruck, but they managed to get the ball out.

“When it reached Derek (Quinnell), he was trundling along and I just saw this black tide coming across. Even if I had caught the ball from him, I doubt I would have made it because I would have been going from a jogging position.

“But fair play to Gareth, he saw Derek wind up, he took the pass and just got there in the corner. To come on at pace and read the pass like that was brilliant.

“I tried to get on the inside of him, but there was no way Gareth was going to pass that close to the line!”

The tone was set and the game continued in a similar vein, with Bevan fending off three All Blacks defenders to produce a typically barnstorming finish in the corner before half-time.

“It wasn’t as if we were thrown together and didn’t know each other, we actually picked up from where we had left off on the Lions tour, passing the ball, moving the ball,” he said.

“We knew who could do what and it gelled on the day.

“The All Blacks could have shut up shop and just shoved it up their jumper and it would have been a different game. But they entered into the spirit of things and made it the occasion it was.”

The 1973 Five Nations, in which he scored two tries in a big win over England, took his tally of caps up to ten, while there was also an outing against Canada in Toronto that summer.

Pivotal moment

But then, in the September, came a pivotal moment in his life as he switched codes, calling time on his Wales career at the age of 22.

“I’d been teaching at Ferndale Boys School while the PE teacher there was away for a year,” he explains.

“But then when I came back from Canada, I didn’t have a job. I asked Cardiff if they could help and they said they could get me a job labouring on the railways. I said I can do that for myself!

“So, for one month of my life, I signed on the dole. I thought this is not going to happen again. Then Warrington came down.

“They said we’ve got a teaching job for you, a nursing job for your wife and a few bob. I said I’ll be up next week.”

So what was his signing-on fee for Warrington?

“I’m not telling you!”

Bevan’s new life up north was to deliver an early culture shock.

“I didn’t know what it was going to be like. I soon found out!” he says.

“My first game was against Castleford. I remember my opposite wing came running towards me and I took him out easy. I had him for pace and strength. I smacked him down all day and got a try myself.

“I had only been up there a week and I thought ‘I am doing well here’.

“Anyway, the next training session, Alex Murphy (coach) calls me over in front of everybody.

“He said ‘Bevan, you are a rubbish tackler’. I wanted to knock his head off!

“He said ‘Right, if you were going to knock me out, where would you aim?’ I went up to him and pointed at his chin and prodded it.

“He said ‘No wonder you are a rubbish tackler. If I was going to knock you out, I would aim there right behind the back of your neck’.

“So that was the beginning of the step-up tackle for me. I didn’t wait and show off, taking the winger, after that. You step up. It’s all about yardage in league.

“I never ever let my winger run again, I was always in his face, bang, bang. It’s very similar to the way rugby union has gone actually.”

In his first season with Warrington, Bevan helped the club win the Challenge Cup, with a 24-9 victory over Featherstone Rovers, while he was back at Wembley for the final again the following year, scoring a try in a defeat to Widnes in front of a crowd of 85,998.

In the summer of 1974, he headed back out to Australia and New Zealand having been chosen for the Great Britain tour. It had not taken him long to adapt to the new code, where he acquired the nickname of “The Ox” for his bullocking approach.

“The truth is I was a Rugby League player born in Wales,” he says.

“I loved it. It was the best move I ever made. I was born to play the game.

“I grew up inside a year or two. I felt great up there, I felt at home and I was a different player.

“It’s a great game and there are great people up there. Northern people are just old fashioned Welsh people with funny accents!”

So how was his old 15-man Union code viewed by his team-mates?

“We played on Sundays, so had a training run on Saturdays,” he says.

“After training, we would go to the clubhouse. If the rugby union international was on, they would switch over for horse racing or darts because they didn’t want to see rubbish tackles. They didn’t rate the Union boys tackling at all.”

Away from rugby, Bevan forged a parallel career as a teacher, with spells at Culcheth High School and English Martyrs School in Warrington, where he coached rugby league. Then came 16 years at Arnold School, an independent school in Blackpool.

He finally hung up his boots in 1986 at the age of 35. He had made 332 appearances for Warrington, scoring no fewer than 201 tries, with his trademark celebration – left arm in the air with clenched fist – becoming a familiar sight at Wilderspool.

His exploits earned him a place in the club’s Hall of Fame, while there were also 17 caps for Wales and six for Great Britain, with yet more tries along the way and the honour of captaining his country.

In the late 1990s, Bevan returned home to become director of coaching for the WRU, a post he held from 1997-2000. He was also assistant coach to Wales boss Kevin Bowring for a spell and then guided the U19s to the final of the 1999 World Cup, with the likes of Michael Owen, Ceri Sweeney, Jamie Robinson, Rhys Williams and Dwayne Peel among the young men under his tutelage.

Since 2000, he has worked at Monmouth School, where he was a boarding master for 15 years. He retired in 2016, but is still there part-time three days a week coaching the pupils.

“I think the purest form of rugby is still in schools,” he says.

“Teachers teach kids the right way to tackle and how to use the ball.

“You move the ball in school. It often changes then once you leave. There is over-coaching. It’s stifling play – you will do this, you will do that. It is taking away the individual flair.”

Speaking to Bevan, it’s clear he’s a man who still cares deeply about the game, while two new shoulders are testament to how committed he was out on the pitch. So now, with the passing of time, how does he look back on his rugby life?

“I think you need some luck – right time, right place,” he says.

“Maurice Richards was a fantastic winger. He scored four tries for Wales against England in 1969, then he goes to play rugby league. All of a sudden there is an opportunity. If he had stayed in the game, I might have taken a long time to get ahead of him.

“Then if Gerald Davies had not been ill, I wouldn’t have played in that BaaBaas game.

“And if Warrington hadn’t come along when they did, my life wouldn’t have taken the same course.

“Everything is an opportunity and you make of it what you can. Sometimes you are lucky, sometimes you miss out. It’s swings and roundabouts. I have had more good things than bad overall and feel very fortunate.”

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Great player. A real loss to union.

This is an excellent article.

I was fortunate to be taught by Mr Bevan when at Culcheth High. Great bloke