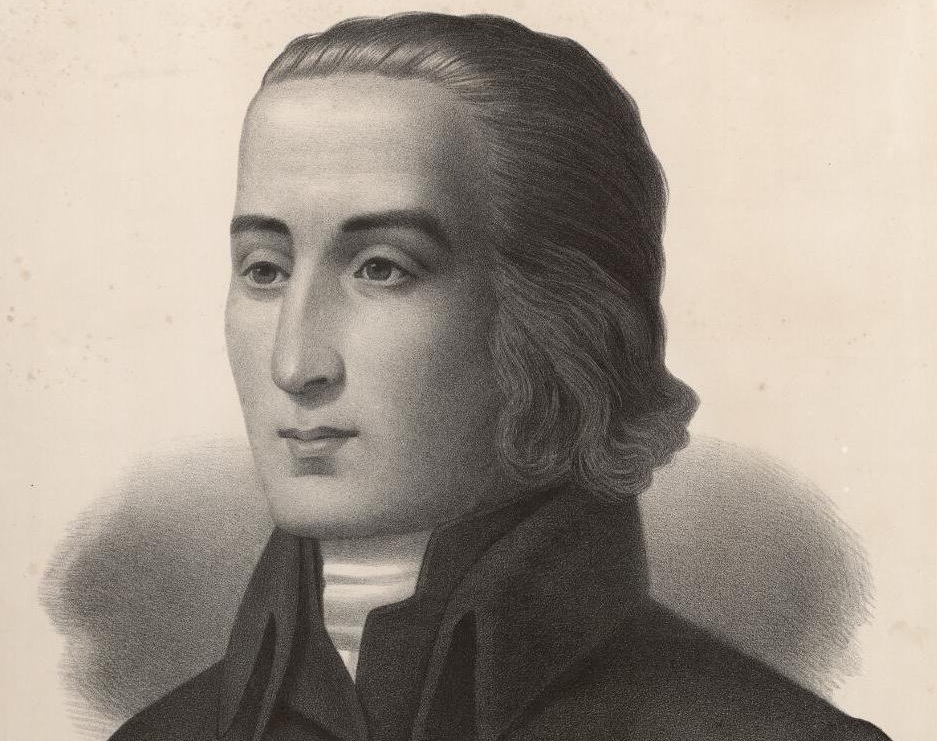

Yr Hen Iaith part 64: a higher love – introducing the poet from Pantycelyn

Jerry Hunter

The career of William Williams, Pantycelyn (1717-1791) provides a striking example of an intensely symbiotic relationship between literature and its immediate social context.

As Derec Llwyd Morgan has written, ‘[y] rheswm amlwg am lwyddiant y Diwygiad Methodistaidd yw llenyddiaeth William Wiliams Pantycelyn’ (‘the obvious reason for the success of the Methodist Revival is the literature of William Williams Pantycelyn’).

While Pantycelyn wrote many other kinds of literature – including prose, and long, experimental poems – the hundreds of hymns he composed helped to shape the reality of Welsh-language Methodist worship.

We might see these texts and their immediate context as mutually constituting, with the one creating and depending upon the other.

Like the other leaders of the Methodist Revival in Wales, Williams experienced a conversion when he was a young man. While studying at the Llwyn-llwyd Academy, apparently intending to become a doctor, he heard Howell Harris preaching and was transformed.

One of his hymns is taken traditionally as referring to this experience: ‘Dyma’r bore fyth mi gofiaf, / Clywais innau lais y nef’ (‘This was the morning I will always remember / I myself heard the voice of heaven’).

Welsh has a variety of pronouns, allowing for the expression of subtle differences in meaning. Rather than writing ‘clywais i’, ‘I heard’, he wrote ‘clywais innau’, using innau, a form of the first person singular pronoun which adds distinctive stress. This purposeful poetic employment of a basic grammatical feature allows the two words ‘clywais innau’ to convey the meaning ‘I heard for myself [the voice that morning which other people had heard before me]’.

William Williams went on to become a deacon in the Anglican Church and served as a curate under Theophilus Evans, a conservative clergyman and extremely important literary figure in his own right (discussed in episode 62 of Yr Hen Iaith).

Religious radicalism

Apparently, Pantycelyn’s religious radicalism was manifest during this time, and Evans played a role in ensuring that the young man was not ordained as a priest. Like other Methodist leaders, he travelled across Wales, preaching and furthering the movement.

The radical break with tradition which put an end to his career in the Established Church is also manifest in his literary endeavours.

A popular anecdote relates how Howell Harris, after hearing Pantycelyn recite one of his early hymns, announced ‘Williams biau’r emyn’, ‘the hymn belongs to Williams’. Whether or not this really happened, successive generations of Welsh Methodists transmitted this story, using it to articulate Pantycelyn’s status as their premier hymnist.

Pantycelyn’s best work is characterized by a startling freshness. Take, for example, the opening stanza of one of his best-known hymns:

Rwy’n edrych dros y bryniau pell

Amdanat bob yr awr:

Tyrd, fy Anwylyd, mae’n hwyrhau,

A’m haul bron mynd i lawr.

‘I’m looking over the distant hills

For you continually:

Come, my Dear, it’s getting late,

And my sun has almost set.’

While composed in the eighteenth century, these lines are easily understood by Welsh speakers today.

Pantycelyn used language readily accessible to his intended audience, employing every-day speech – often inflected by his native Carmarthenshire Welsh – and an unpretentious vocabulary.

Simplicity

The formal aspects of his hymns suggest an aesthetic grounded in simplicity; he completely avoided the traditional strict metres and the complex cynghanedd system, employing simpler free meters instead. This formal simplicity is the vehicle for conveying powerful expressions of deep spiritual experiences.

There is also something daring about these opening lines. If you were reading them for the first name and didn’t know that they belonged to a hymn regularly sung as part of religious services, you might think that this was a love poem.

The persona – the character we hear speaking in the poem – is a worried lover, ‘continually searching’ for his ‘Dear (one)’. These few short lines convey the worry tinging the love in different ways; he is searching all over of his love, his sun has almost set and it’s getting late.

The next stanza takes us in a new direction, revealing that it is a heavenly love which he’s searching for, a force which makes all earthly loves seem insignificant:

Trôdd fy nghariadau oll i gyd

’N awr yn anffyddlon im;

Ond yr wyf finnau’n hyfryd glaf

O gariad mwy ei rym!

‘All of my of loves now have now

Become unfaithful to me;

But I am delightfully sick

From a more powerful love!’

Back in the fourteenth century Dafydd ap Gwilym complained that he was sick because of his love for a woman, employing a literary trope which already old in his day. In this hymn Pantycelyn co-opts that literary language of love and employs it to express both his love for God and God’s love for him.

First person

One of the most obvious features of this hymn is the way in which it purports to relate personal experience. It is in the voice of the first person: ‘I am looking’, ‘my Dear’, ‘my sun’, ‘my loves’, ‘unfaithful to me’, ‘I am delightfully (love-)sick’.

Focussing on this helps us understand the relationship between literary text and historical context. The poet is writing about personal experience, and he has fashioned a persona who relates that experience in a dramatic first-person voice. Yet these words were meant to be sung by a group of people worshipping together.

Imagine that act of singing. Each person sings these words, thus taking on the persona of the spiritually love-sick individual. Each individual singer contrasts her/his/their higher love with all earthly loves, praying for strength to remain faithful and to continue to praise that higher love.

If a singer’s religious beliefs and experiences align with those being expressed in the hymn, then singing these words should be a very intense and very personal experience. Yet the singer is part of a group of individuals, all united by the same individualistic experience.

Paradox

As Derec Llwyd Morgan observed, William Williams Pantycelyn incorporated this apparent paradox, itself a defining feature of early Welsh Methodism: ‘Un o baradocsau niferus Methodistiaeth Fore oedd ei bod ar yr un pryd yn ingol bersonol ac yn ystyriol lwythol’ (‘One of the numerous paradoxes of Early Methodism was that it was at one and the same time agonizingly personal and contemplatively group-orientated’).

During his long life Williams Pantycelyn would published more than 90 of his works, all fashioned in one way or another so as to serve that particular group.

His literary career also helps us understand the growth of the Welsh-language publishing trade. As was stressed in earlier episodes of Yr Hen Iaith, printing had been restricted by law to a very few locations in England. It was only in 1695 – some 22 years before Pantycelyn was born – that this legal restriction was loosened.

By the time Williams began composing his first hymns, there were printing presses in several Welsh locations. In a very real sense, he was the right poet in the right place at the right time.

Further Reading:

Derec Llwyd Morgan, Williams Pantycelyn (1983).

Derec Llwyd Morgan, Y Diwygiad Mawr (1981).

Derec Llwyd Morgan, The Great Awakening in Wales (1988).

Episode 62 in this series: https://nation.cymru/culture/yr-hen-iaith-part-62-crafting-a-mirror-for-welsh-identity-drych-y-prif-oesoedd/

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.